You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Blackboard

Data dashboards and performance feedback can motivate middle-range students to work a little harder to earn a desired grade, a new study found.

The study, conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan School of Information and the educational technology company Blackboard, explores a growing trend in higher education -- that of collecting data about students and presenting it to them at important junctures during their college careers, with the hope that doing so will lead to higher grades and improved retention and graduation rates.

“There is an assumption that providing students with dashboards of information and data about their performance will help them,” John Whitmer, director of research and analytics at Blackboard, said in an interview. “It’s becoming pervasive in educational technology.”

But the actual impact of giving students access to their data has not been thoroughly studied, Whitmer said. Usually the information is delivered to students by people who are trained to analyze the data, such as advisers and faculty members. If colleges were to cut out those middlemen, he said, would students understand the data, and would that understanding motivate them?

The researchers tested those questions in a simulated class. Forty-seven students volunteered for the experiment, and they were split into four smaller groups: first by their grade point averages (with the split running between students with a B average or higher and those below a B), then by the type of performance feedback the system gave them -- simulating either high performance (“You’re a rock star in this course” or “You make it look easy”) or low performance (“You haven’t been around much lately” or “The course got you down? You can do it”).

The students received performance feedback -- as well as a graph showing their performance compared to the class average -- at three crucial points during the simulated course: early on in the semester, right after the midterm and just before the final. They were asked to imagine what, if any, impact the feedback would have if they had received it during a course they had already completed -- for example, an important major requirement.

Students in the experiment were asked to comment on each of the three rounds of feedback. They then took a final survey in which they reflected on whether the feedback could motivate them to change their behavior if presented to them in a real class.

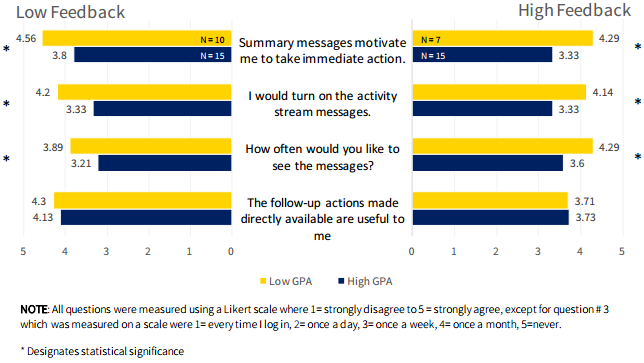

The findings suggest that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to giving students data-driven feedback about their academic performance. Some students with high GPAs said the feedback made them feel smart, since the graphs consistently showed them ahead of the class average, while others with high grades said it discouraged them from working as hard.

Generally, students said they were interested in having access to the dashboards, even though some of them questioned whether a connection between frequently logging in to a learning management system and academic performance existed in the first place.

One statistically significant finding stood out: students with a GPA of B or lower said they would be more likely than students with higher GPAs to use the feedback feature and take action in response to what the system was telling them -- for example, seeing an adviser or talking to their professor.

That finding runs contrary to what the researchers expected going into the experiment. Whitmer said he assumed high-performing students would benefit most from seeing how they compare to the course average -- like “super athletes looking to optimize their performance,” he said.

While the study may hint at a use for data dashboards that increases academic performance among at-risk students, the researchers stressed that further studies are required. Although their study grouped half of the participants into a low-GPA category, those students were in no way in danger of failing. The researchers instead described them as students who may have been used to earning A’s in high school but found themselves earning a B average or below in college.

“What this kind of research can help us figure out is which students can benefit most from feedback,” said Stephanie D. Teasley, research professor in the School of Information.

Michigan previously built a data dashboard initially designed for advisers, Teasley said, which inspired the university to work with Blackboard on the study. The ed-tech company supplied both technology and funding for the study. It is not yet peer reviewed, but the researchers plan to submit it to a scholarly journal, she said.

One comment the researchers received from some students in the experiment shows that feedback meant as encouragement can accidentally backfire. These were some of the students who received the message “You make it look easy” -- but instead of seeing it as a compliment, the students felt such a message cheapened the effort they put into their studies.

“They knew it didn’t come easy to them,” Teasley said. “It was the result of hard work. Those are the kind of nuances that this research can reveal to help us shape these tools.”