Why China Wants to Slow Down Its Own Economy

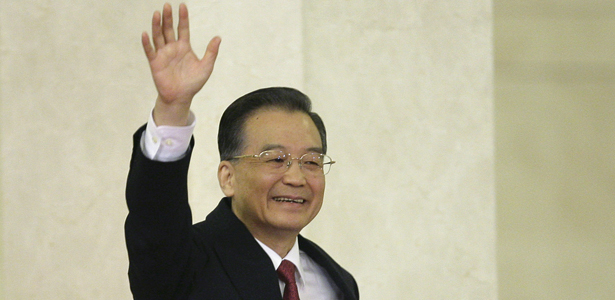

Outgoing Premier Wen Jiabao called for reducing growth, a sign of China's concerns about rising inequality.

As China's annual National People's Congress draws to a close, its most substantive portions came from Wen Jiabao's work report, a sort of Chinese version of the "state of the union." It set the tenor for economic objectives in 2012 -- Wen's final year in office -- including a call for slower growth. Wen set a target of 7.5% GDP growth. That would be the first time annual GDP growth dropped below 8% in years. Still, China has tended to overshoot its GDP targets, so the target-setting exercise does not necessarily reflect underlying economic performance. Instead, the target serves as a political signal to remind each level of government that the days of GDP-worship need to end, and that they will have to make way for the long-delayed restructuring.

This is not merely sloganeering, as the government realizes that rebalancing the economy necessarily entails a higher tolerance for reduced growth. It is important to understand the context in which Beijing decided to lower the target. As I wrote recently in the China-US Focus:

The central priority for the Chinese government is no longer simply about economic growth. Rather, the chief challenge is dealing with the sociopolitical tensions and inequalities that are products of that growth. On these two fronts, the Wen administration record has been far less than stellar. Moreover, facing the unprecedented ferocity of public opinion, the government is increasingly having its feet held to the fire on issues of social equality and quality of life...

... After 35 years of breathless expansion of the economy, the growth story is less compelling for the Chinese public. Growth alone is no longer the panacea that papers over structural problems or ensures political legitimacy of the regime.

Why? Because the Chinese public, particularly the rising middle class, has started to notice that for all the talk of the Chinese economic miracle, they have not miraculously grown wealthy. Some have indeed become obscenely rich, which only serves to reinforce the sentiment that the system is tilted towards the few and stacked against the many. Adding fuel to the fire is that those who have been blessed by the growth miracle happen to be the political class itself or just one degree removed...

... But it is the nearly 3,000 delegates of the NPC who broadly represent the establishment that has disproportionately benefited from China's economic pie. Of the thousands of delegates, 70 of the richest have a combined net worth of $90 billion, according to Bloomberg. To put that figure in context, it translates into more than $1 billion per delegate, while the average urban income is just $3,500 in 2011...

Wen is setting up a daunting task for China, and I suspect much of the dirty work will be inherited by the incoming leaders. Inequality is now an issue of long-term political stability. The Communist Party has built itself into a middle-class establishment party, where its constituency's prosperity is tied to the enduring ability of the party to deliver on its constituency's demands. For a while, it seemed like general economic growth, the kind that makes everyone better off, would be enough.

But that will no longer suffice. Emerging signs suggest that China's elites are not particularly satisfied with the governance mandate monopolized by the party, especially as their expectations rise significantly on what a political system ought to deliver -- and it isn't just GDP. Some of the wealthy Chinese feel that they cannot adequately protect their assets in a country where legal institutions are so weak. And others simply want protection for themselves in the form of social safety nets and welfare policies. In fact, some of the extremely wealthy have started to vote with their feet by sending their children to the U.S. or other western countries, or even applying for green cards as a contingency plan. To capture the sentiment most simply, at the risk of over-generalization, it is this growing sense that the system does not afford adequate protection to the majority, only to a sliver of the privileged minority.

Yet few are seriously advocating any sort of regime change to tackle the problem. In fact, many do not think a democratic regime would do much better. But this should still be disconcerting to the Chinese leadership, as the constituency it has so methodically cultivated over the last decade or more is now eroding.

Indeed, Carnegie Endowment scholar Yukon Huang articulates a similar dynamic, writing recently in the Financial Times:

For all of China's economic successes - which lifted some 600m out of poverty - income disparities nevertheless have ratcheted up with the gini coefficient now at 0.47 compared with around 0.25 in the mid-1980s. This has fostered a sense that the system is uncaring, and that opportunities are now being determined by one's status rather than initiatives.

There is a strong link between the growth in social unrest and the reality that the reform process launched by Deng Xiaoping three decades ago has stalled. Rising social tensions come broadly from two forces, namely limitations of China's national budget and banking systems in addressing distributional needs and distortions arising from controls over use of land and labour.

For all the talk of China less willing to bend to the demands of foreign powers, that has always been a second-order concern if you're Wen or Hu Jintao. Instead, bending to the will of the domestic public, or at least meeting it half way, seems a more urgent matter.