Janice Dickinson is in a silk robe, smoking a cigarette and descending a flight of steps in her garden, which is built into a hillside in Beverly Hills. She is, at one level, in her element, surrounded by photographers and stylists, a happy reminder of her heyday as a supermodel in the late 1970s. At the same time, she can’t be seen to be enjoying herself too much: the 60-year‑old reality TV star is meeting me in her capacity as one of the scores of women who have accused Bill Cosby of rape or sexual assault – accusations the actor has either not responded to or denied.

“She’s more successful than him anyway, now,” says her friend, Stephen, as they re-enter the house.

“Except in the bank,” Dickinson says, drily.

For the rest of the shoot, Dickinson seems high on adrenaline, bantering with the photographer, elaborately rolling her eyes and throwing herself gamely about in line with her contractual obligations as a reality TV star. “That’s an egg fart,” she says to Bella, the bulldog who slumbers at her feet once we’re settled on the sofa. Dickinson starts gagging. “That is vile. Go, Bella! Go over there!”

During the course of the interview, Dickinson veers between this, her reality show persona – raucous, sarcastic and camply melodramatic, a tone that Cosby’s lawyers have already made capital of – and something quieter and altogether more dangerous.

The image of the “good” rape victim is one that, thanks to decades of campaigning by women’s rights advocates, even disinterested observers have an understanding of these days; the fact that securing a conviction for rape rests in large part upon the perceived virtue of the victim. In the case of Dickinson and the other women accusing Cosby, criminal charges are out of the question. Unlike murder, rape has a statute of limitations in the US, which varies from state to state but averages around 20 years. Dickinson alleges she was raped by Cosby in 1982. Cosby denies this.

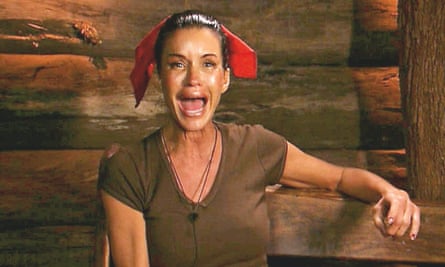

That leaves the civil courts and the court of public opinion, wherein Dickinson is an easy target for derision. Her face has the permanently surprised look often associated with cosmetic surgery. She reels off the reality shows she has been on: “I did I’m A Celebrity… twice. I did Come Dine With Me in London. I did Scream! If You Know The Answer. I produced my own TV show, the Janice & Abbey show [with model Abbey Clancy]. I was a judge on America’s Next Top Model; I was a judge on Germany’s Next Top Model; I was a judge on Benelux Next Top Model; I was a judge on every Top Model all over the world.”

She also did Celebrity Rehab, mention of which makes me wince.

“But that’s what I do,” she says. “That’s my income. I’m a pop culture icon.”

As a result, there is a lot of lively background material on Dickinson, which Cosby’s lawyers have called on to assert, in a recent statement, that “lying is part of her brand”, that she is “cashing in” on the “media frenzy” around Cosby, and that, “in her quest to remain in the public eye, Ms Dickinson has actively cultivated a reputation for outrageous behaviour that includes substance abuse, mental lapses and lying”. Dickinson has launched a defamation suit against the actor. She has also called him a “pig”, a “monster”, and said that, if she were to meet him in person, she would like to say to him, “Just stop. Please cut off your testicles and your penis”, the sort of statements media trainers call “injudicious” and casual observers call “nuts”. It’s an irony of alleged rape victims that the emotional fallout that often follows from a sexual assault – anger, “instability”, a desire for revenge – is the very thing that may undermine their credibility as witnesses.

Dickinson doesn’t care; or rather, she has learned through long experience that there is more to be gained than lost from saying what she thinks. Her outrageous behaviour is largely of the naughty, adolescent kind (she recently saw Sinéad O’Connor at the Chateau Marmont, for example, and started singing Nothing Compares 2 U very loudly in her direction; O’Connor turned on her heel and fled), and is a bravado rooted as much in Dickinson’s childhood as in her showbiz life.

She grew up in Hollywood, Florida, where her mother was a nurse and her father a merchant seaman. He was also, she says, a violent paedophile who abused Dickinson and her elder sister so that when she left home bound for New York at the age of 18, it was with the kind of hard-baked resolve that can be mistaken for rudeness, a “flamboyance” driven by the conviction that moderation is the luxury of girls from good homes.

“I didn’t do very well in school, because I had a bad dad,” she says in a sing-song voice to acknowledge the cliche, a flippancy that dissolves in the pages of her memoir that chronicle those years. When she was seven, her father came into her room and tried to force himself on her. When she refused, he punched her.

“There are passive women and passive men. I was aggressive. Thank God, I had an angel on my shoulder.” Her father stayed away from her, sexually, after that, but would lie in wait and punch her when she came through the door. Repeatedly, he told her she was rubbish and would come to no good.

“I didn’t have fear,” she says. “I would take my surf board and swim way far out to sea. But I was afraid of him at night.”

Dickinson first met Cosby in the early 1980s, when he set up a meeting with her, dangling the possibility of an acting role in one of his projects, she says. Cosby was in his mid-40s, an actor and comedian who was about to become a lot more famous with the launch of The Cosby Show, then in early development. Dickinson, who was 27, was highly visible, too; framed photos of her magazine covers from that era line the walls of her home. Nothing at the lunch struck Dickinson as odd; he was charming, she says. A few months after the meeting, she checked into rehab in Minneapolis – “I’ve never seen snow like that in my life” – and Cosby sent her a bunch of long-stem red roses. “How the fuck did he get the number? He must’ve gotten it from the modelling agency. My instincts were: that’s weird. He’s married. I’m a Catholic. I don’t cheat.”

Dickinson has left every man who ever cheated on her, she says, and her reputation for being a little rowdy in public is undercut by fastidiousness at home. Visitors are advised to remove their bags from the kitchen table and coasters are slid under their drinks. When Chester, the labrador, jumps on the sofa, Dickinson moves him to put a blanket down first. I ask how long she has lived here. “In this hole? Oh, I’ve lived here with Rocky for three years.”

Rocky is Dr Robert Gerner, a psychiatrist and Dickinson’s fiance, currently laid up in one of the bedrooms after knee surgery. Dickinson’s 21-year-old daughter, Savannah, is also home for the summer from college, which she indicates by pointing to a large pile of dirty laundry on the floor. (Nathan, her 28-year-old son, lives in Atlanta, where he’s a TV producer.) For Beverly Hills, it is a modest family house; Dickinson has never been good with money. While her mother, who lived through the second world war, used to beg her daughter to save what she earned, Dickinson did everything she could to extinguish the memory of her childhood, including trying to spend her way out of it.

“The first pay cheque I got I blew on a pair of Yves St Laurent pants in New York City,” she says. “At Bloomingdale’s. They were fabulous.” She would go out with a group of friends and buy 18 lobsters, a grandiosity and generosity that is in evidence today. When I comment on a framed antique map of Silesia hanging on her kitchen wall, she says Rocky collects them and asks, “Do you want a map? We have loads.”

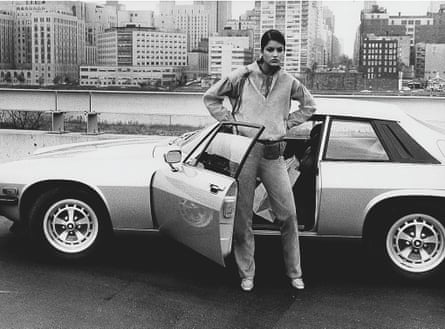

To begin with, however, she was just another broke, ambitious girl in New York, trying to make it as a model. This was in 1973, when she was in her late teens, and for the first few months in the city she lived with a friend’s family who had moved up from Florida, spending the days pounding the pavements with her portfolio. At 16, she had won a local modelling competition, but her ambition predated that by 10 years, to when she first picked up a fashion magazine and decided that life in the photos looked good. “I wanted to be flooded in otherworldly light.”

Her approach, during that first year in New York, was one of “blind faith. I wouldn’t take no for an answer”. She also had her father’s insults ringing in her ears. “I thought, I’ll prove you wrong. You’re wrong.”

The reality of the modelling world was less charming than the ads in the magazines. “It was hideous,” Dickinson says, “because my look wasn’t the look that was selling. Eileen Ford told me my lips were too ethnic.” She picked up small gigs, serving her dues in Paris and Milan, earning a pittance and working long hours. She met a jobbing musician called Ron Levy and they married, then divorced. At the time, she was sober. “There was no way I could have been on substances and worked like that,” she says. “Up at 6am, at work at 7.30am. Then get on a plane and go to London. I worked really hard in the first year. I couldn’t afford anything. I worked my ass off.” There is a pause. “Do you want some cheese?”

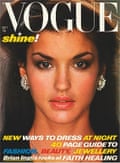

Eventually, she caught enough breaks to start making headway, and by the late 1970s Dickinson was working with Richard Avedon for American Vogue, Guy Bourdin for French Vogue and flying around the world first class. “Before Kate, Christy, Naomi and Alek Wek came along, I’m flying to Japan with Calvin Klein and Iman. I just worked. I was Versace’s favourite. Issey Miyake’s favourite.” (She was not Georgio Armani’s favourite, however, after mistakenly addressing him as “Gianni” during a shoot.)

By the early 1980s, the workload was starting to take its toll. There was a lot of champagne and cocaine. There were the dog-end years of Studio 54. And there was Dickinson’s second big relationship, with Michael Birnbaum, a photographer, which also collapsed. Birnbaum is Savannah’s father. (Dickinson had Nathan with her second husband, Simon Fields, a producer.)

For the next few years, she enjoyed her celebrity status and dated a series of high-profile men including Mick Jagger, Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson. In No Lifeguard On Duty, the first of her three memoirs, she recounts these affairs with a jock-like joie de vivre that is very different in tone from the long, sad tale of waiting by the phone that characterised Anjelica Huston’s experience with some of the same men.

“Yeah,” she says. “She’s partly a product of the times, though. She’s older than me. And I didn’t grow up in the lap of luxury like she did.” There is a pause. “Do you want some foie gras?”

In 1982, her friends, family and then boyfriend, Charlie Haugk, performed what amounted to an intervention: “They said, ‘Janice, you need to slow down and stop working so hard, stop going out at night, because you’re going to start to lose clients.’ I said, ‘Ah, you’re all just jealous.’”

But eventually she agreed to go to a rehab clinic in Minneapolis and, shortly after leaving, flew to Indonesia to shoot a calendar. She took Haugk, a male model, with her.

While she was there, Cosby rang her at the hotel. “I said, ‘How did you get my number?’ He said, ‘I can find anybody.’ He says he wants me to fly to Lake Tahoe. He says he wants to help me with my career. My boyfriend, Charlie, said, ‘You should go, he’s a big star.’ I said, ‘OK, I’ll go, I’ll stay a couple of days, and I’ll come back.’”

If Dickinson was suspicious of Cosby’s motives, she was also confident that she knew how to look after herself. When Cosby proposed flying her economy, she said “No, I don’t take economy. First class.” His fame offered a level of surety. And besides, they had talked during their first meeting about how he might help her break into the record industry. “If there wasn’t a good possibility that he was going to advance my singing career, and that he was going to put me on The Cosby Show, I would never have gotten on that flight.”

I’m not sure I’d want Dickinson as an enemy. She is dogged. She has, for all her apparent boisterousness, an unsparing moral sense. And she’s smart. She was a big reader as a kid, she says, and along with all the National Enquirers and People magazines stacked up in her house, I see Harper Lee’s new novel and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s essay, We Should All Be Feminists.

The details of what happened when Dickinson got to Lake Tahoe will come up in the defamation suit. Cosby’s attorney has specifically addressed her allegations and denied them on behalf of his client, claiming that “documentary proof and Ms Dickinson’s own words show that her new story about something she now claims happened back in 1982 is a fabricated lie”. Dickinson claims she had dinner with Cosby, during which she complained to him of having menstrual cramps. After dinner, she says, he gave her a pill with some red wine. The last thing she remembers from that night, she says, is blacking out with Cosby on top of her.

“It’s something I will never forget: the smell of his breath – coffee. He didn’t drink. Cigar breath. I remember what he was wearing: a patchwork robe. A large gold Rolex. A wedding ring that said BC. He had on a brown velvet hat, like a pimp hat.”

Where was he when she woke up?

“I was alone.”

This was not the account Dickinson gave in No Lifeguard On Duty. In the memoir, they go upstairs after dinner and Cosby slams the door of his hotel room in her face after she refuses to come in for a nightcap. The draft manuscript, she says, contained a different story and lawyers for her publisher made her take it out.

When Dickinson woke the following morning, she was in pain, she says. She claims her pyjamas were off and there was semen between her legs. Did she tell anyone? “I can’t say because I’m in litigation. I told several people. I told… I can’t say, because we’re going to use that.”

Did the alleged rape come up over the years in therapy?

“No. Because I was trying to figure out, in my late 30s… I went to see a therapist four times a week. I was trying to figure out where I stood with my dad.” And Cosby? “The one horrible regret – that I didn’t have the wherewithal to fight. I was slipped a pill.”

As if to re-ground herself, she says, “I have raised two of the most incredible children. Who have also been embarrassed.”

Are they angry? “What do you think? Of course they’re angry. They’re disgusted. You see, my son would have probably preferred that I didn’t go public. But then in November, when the other women came forward, I knew – because I love women and I love my sister, and I’ve worked with Hispanic women who’ve been raped – that I had to lend my name to it, because I have a name. Reality star. Television is a very powerful vehicle.”

Since last November, the number of women making similar allegations against Cosby has climbed to more than 40. Dickinson’s fame guarantees her a platform, but will also be beneficial to Cosby’s legal team. To have spoken as much in public as Dickinson has is to guarantee variations in the stories she’s told.

One of the reasons Dickinson didn’t go to the police at the time, she says, is that she thought it would ruin her reputation. “I was at the top of my game. I worked so hard for many, many years. I just didn’t want the jobs to end. I didn’t want to embarrass my family.”

She didn’t want to embarrass herself, either; her assumption was that no one would believe her. After all, she says, Hollywood is a town that forgave Polanski. “I didn’t,” Dickinson snaps. “I went on a date with Roman Polanski. It was set up by a hairdresser. He took me to dinner. And he didn’t say three sentences to me, I promise you, until I got into the car and he said, ‘Are we having sex tonight?’ I said, ‘No, I want to be dropped off at my house right now.’ Which they did. Roman Polanski: he should be in jail.”

In 1982, she says, “I didn’t know what a rape kit was, and even if I did, I just recently read that there are thousands and thousands of unprocessed rape kits just sitting there. These monsters are still allowed to vote, still allowed to go out and do it again, and that’s what makes me mad. I have a daughter, she’s 21, she’s a senior in college. She’s proud of me. All of her friends are proud.”

Dickinson would like the law governing the statute of limitations for rape to be changed. “Rendering any person helpless with the sole intention of having sex with them is rape. There should be no statute of limitations because – look, I’m a God-fearing patriot, I’m a proud United States woman who has raised two children as a single mother, and I’ve kept this secret about my dad for several years, and I kept the secret of Bill Cosby since 1982. If a woman gets raped, it’s a crime. We as women should band together and make Obama change the law. A man should go to jail for the crimes he’s committed.”

Since November, Cosby has lost a lot of commercial deals. Dickinson itemises them: “They took away Cosby’s Netflix deal. Thank you to the head of Comcast, Ted Harbert, thank you to the powers that be that took his reruns down, his Disney statue in Orlando, they stripped him of his doctorship at Temple University. He can’t get arrested.”

But losing his business makes up for some of that?

“Well, yeah. You hit him where he breathes: his pocketbook.”

Dickinson says she hasn’t received a penny for the interviews. Did Cosby ever offer her money?

“No. He only offered me red wine and a pill.”

She never saw him again after that night. Is it empowering, talking about the alleged rape?

“No.”

It’s only distressing?

“It’s not distressing. I’ve been a believer of Eckhart Tolle for many years, not ever to pity myself, ever. We just get back on the bicycle and ride. Kids, do your homework, be a good member of the community. If you do something wrong to someone, call that person up and say sorry. I have principles. I have morals and principles.”

I ask if she’s ready for the fact that Cosby’s lawyers will almost certainly use her history of substance abuse to try to destroy her credibility.

“I am sober today, through the grace of God,” she says. “I was at a 12-step meeting this morning, as I am every morning.”

They’ll still fling it at her, I suggest.

“They can fling all they want. I did not consent to being raped. I didn’t consent to it. I didn’t.”

Later, as Dickinson is bagging up the garbage, and before she goes outside to water her tomato plants in the evening light, I ask if it makes sense to say that she’s over it – any of it? “You never get over it,” she says. “But I was in the car one day at a stop light and I suddenly thought: I forgive myself.” You forgive yourself?

She smiles. “For being a victim. What could I have done?” Her mind ranges back to the original crime. “I was seven years old.”

I ask how she rebooted. There is a long pause. “I think humour is a big thing. Humour saves lives.”

And what does she say to those who insist she is jumping on the bandwagon; that by accusing Cosby she is merely courting publicity?

She narrows her eyes. “I say to them, piss off. Are you insane?”

- This article was amended on 3 August 2015. Stephen is Dickinson’s friend, not her assistant.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion