Indonesia’s Indo-Pacific vision is a call for Asean to stick together instead of picking sides

- The 10-member bloc is discussing a shared vision for the Indo-Pacific, as big powers offer competing ideas for their engagement in the region

- Indonesia’s proposal isn’t aimed at changing Washington or Beijing’s behaviour, but it promotes an alternative regional order that can accommodate all interests, even if problems among countries remain.

Asean is having ongoing discussions on its vision for the Indo-Pacific, as the world’s two largest economies offer opposing ideas for their engagement in the region.

Leaders of the 10-member bloc want cooperation to be governed by openness, transparency and inclusivity, while maintaining a rules-based approach that highlights the centrality of the association itself.

Indonesia has been leading the push for Asean to declare its vision for the Indo-Pacific. A joint statement would be ready by next year, according to an announcement made by Indonesia’s foreign ministry at the end of the East Asia Summit in Singapore on November 15.

Jakarta’s proposal was unveiled at a gathering of Asean foreign ministers in January and is largely based on ideas laid out by Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi earlier this year.

It wants an Indo-Pacific “regional architecture” similar to Asean’s “ecosystem of peace, stability, and prosperity”, which would draw on Asean-led mechanisms and be based on the principles of inclusion, confidence building and international law.

China rejects claims Apec diplomats tried to ‘barge’ in to influence communique

These ideas reverberate through the “Indo-Pacific Outlook” concept paper, drafted by Indonesia and circulated to other member states for further input. The revised draft spotlights the centrality of Asean and calls for existing mechanisms in the evolving regional architecture to be strengthened.

It views the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions as closely integrated and interconnected, describing them as a single geostrategic theatre.

Unlike other frameworks dealing with the Indo-Pacific that focus on shared values such as democratic norms, this paper emphasises common interests such as development and prosperity. It further seeks to prioritise cooperation in maritime affairs, regional connectivity and in achieving the United Nations’ global sustainable development goals.

This desire stems from concerns that existing visions of the Indo-Pacific by larger powers are exclusionary and could divide the region into opposing camps

These broadly defined objectives are not novel; Asean and other regional organisations have emphasised similar goals for years. They’re also relatively unobjectionable and do not contradict existing conceptions of the Indo-Pacific.

But they do seem more aspirational and normative than strategic and practical.

They’re not immediately impactful goals, either, and they will not address pressing strategic challenges.

The concept paper is likely to do little to change Beijing’s machinations in the South China Sea, nor will it stop the US from conducting freedom of navigation operations in the area.

Instead, the Indo-Pacific Outlook seems to be formulated with inclusion in mind – getting all the regional powers, including China, to agree on a broad multilateral regional architecture.

This desire stems from concerns that existing visions of the Indo-Pacific by larger powers are exclusionary and could divide the region into opposing camps – reigniting old divisions that Asean-led mechanisms have sought to manage for decades.

Apec summit ends without agreement as US and China’s deep divisions over trade emerge

The competing views of China and the United States on the Indo-Pacific bubbled to the surface at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Papua New Guinea last week.

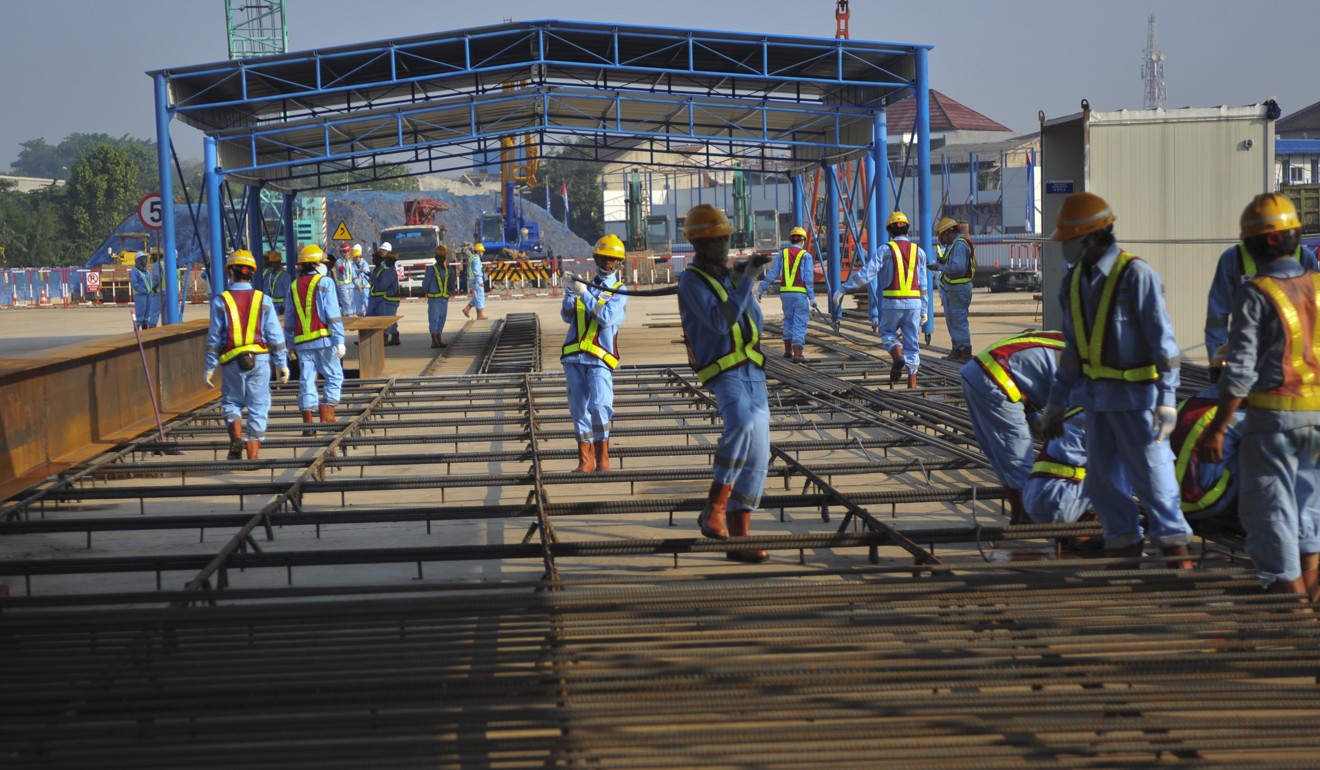

Chinese President Xi Jinping sought to fend off critics of his trillion-dollar global infrastructure development programme – the Belt and Road Initiative - rejecting suggestions that it was creating a far-reaching “debt trap” for poorer nations and instead promoting it as transparent and “an open platform for cooperation”.

US Vice-President Mike Pence, meanwhile, urged governments in Asia to get on board with Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy, which is backed by Australia and Japan, and plans to similarly prioritise infrastructure development.

But an Indo-Pacific under either a Pax Americana or a Pax Sinica is unsustainable and will face resistance. Divisive multipolarity and any ensuing fracturing of the region is also a non-starter.

The Indo-Pacific Outlook is, therefore, an alternative regional order that hopes to accommodate all interests, even if it cannot solve the problems among countries.

According to the draft concept paper, regional powers should seek to “strengthen and optimise” the East Asia Summit (EAS) as the most inclusive platform for strategic dialogue in the region that is central to Asean-led mechanisms.

As a gathering of regional leaders, the EAS is envisioned as the premier decision-making venue for strategic Indo-Pacific concerns, leaving practical cooperation to be implemented or pursued by other bodies such as the Asean Regional Forum and the Asean Defence Minister’s Meeting Plus.

Yet there are no specific plans to move towards this model of governance soon, nor has a division of labour between the implementing institutions been established. There is also a question over how the EAS can streamline the Indo-Pacific agenda and ensure implementation throughout Asean’s mechanisms without a dedicated secretariat office or an executive council.

When all is said and done, the Indo-Pacific outlook that Asean agrees on may be tangential to the region’s more pressing short-term challenges. But in the long run, this vision is the most inclusive yet and represents a workable alternative that can stabilise the regional balance of power. This is particularly the case if Asean could institutionalise – not just strengthen – the EAS.

Asean may be a slow moving force. But if given the right push, the results of its work will be worth the wait.

Evan A. Laksmana is a senior researcher at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Jakarta, Indonesia