It is late October, 1978, in Colorado Springs when Ken O’Dell, a closet member of the newly resurgent Ku Klux Klan, receives an encouraging sign that his strategy of placing ads in the personal section of the local paper for new recruits has met with some success. Ken has been sent a letter from a man called Ron Stallworth. Ron, he says in his letter, wants to “further the cause of the white race” – and to join the Klan. Before long the two men are in enthusiastic telephone contact. Ken, who loathes blacks, Jews, Catholics and any other minority he can think of, sees Ron as a kindred spirit. Indeed, Ken is so impressed by Ron that, over the coming months, he will not only make sure that Ron gains membership and full access to the Klan, but he’ll even tout him as a future leader of the local chapter. Unfortunately for Ken, there are a couple of things about Ron he doesn’t know –and won’t know until 28 years later when Ron reveals them in a newspaper interview. First, Ron is an undercover police officer. Second – and this never fails to crack Ron up every time he thinks of it – Ron is black. “I was having a lot of fun,” he says.

The story of how a black police officer infiltrated the KKK is at first so hard to wrap your mind around that you may question how it can possibly be true. But once you’ve taken account of the state of late 1970s technology, it becomes easier to understand how such an audacious and thrilling police sting could ever have come into being. No internet, no smart phones: resurgent underground terrorist organisations have to rely on letter writing and telephone calls for their secret communications. Ken has no way of knowing, for example, that the voice on the other end of the telephone line, fulminating against “slaves” and “mud people” belongs to anyone but what Ken likes to call “an intelligent white man” – like himself. Ken falls for it.

“Fortunately the people I was dealing with weren’t the brightest bulbs in the socket,” Ron says. What happened next is the proudest, most off-the-wall moment of his career in law enforcement. “It was so hilariously funny that this was even taking place. But funny as it was, it was an investigation that we took seriously – because the Klan’s intent was very serious.”

I stumbled across Ron’s story last year in an article written in 2006 in the Deseret News, a Utah newspaper. Ron was well known for having set up the state’s first Gang Task Force, but when asked to name his most significant career achievement he dropped a bombshell and said: “The year I went undercover with the KKK.” The story went viral.

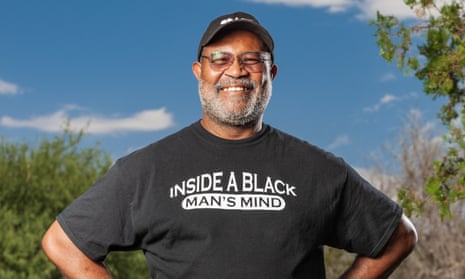

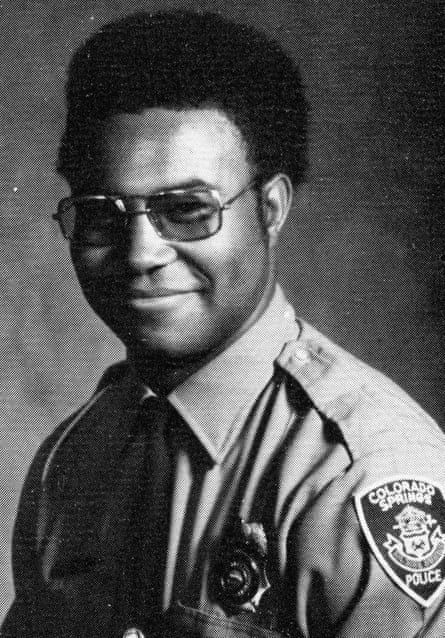

I tracked Ron Stallworth down in El Paso, Texas, the border town where he’d grown up. Ron, now 65, is living a comfortable married life. He is retired, though still deeply loyal to the police force, and there is a grouchy rebelliousness to him: “I don’t care what they think,” he says calmly when I ask him what his former colleagues, his parents, the KKK, the world make of his surveillance work, or anything else. Ron was 21 when he joined the police as a patrol officer – the only black person working in the entire department. The Klan investigation came out of the blue, four years later – what a gift to a spirited and ambitious young cop. At one point in our conversation he opens his wallet to show me a memento: his Klan membership card, issued in 1979. He was ordered, on its termination, to destroy all evidence of the investigation, but it’s typical of Ron’s rebellious nature to have kept the card anyway.

There’d been talk over the years of his story being made into the film – it had never happened. But shortly before I first made contact with Ron, the director Spike Lee had finally given the project the green light. Ron tells me he is very excited, “somewhat overwhelmed”, that the film director is flying him to New York for a read-through of his film adaptation of Ron’s life. “Spike has been very respectful, he has said he values my opinion.” BlacKkKlansman is going to be a return to form for Lee, predict critics: a strong contender for film of the year when it’s released next month. Lee cast John David Washington as the younger Ron. The older Ron admits that, as an admirer of Denzel Washington, he is excited to see what the actor’s son will make of the role.

It’s baffling that it has taken more than two decades for such an astonishing story to be adapted. “It wouldn’t have been made if Trump wasn’t occupying the White House” (Ron won’t dignify the present incumbent with the word “President”): Charlottesville, where last August neo-Nazis and white nationalists clashed with anti-fascist demonstrators, accelerated Lee’s race to get the film finished. The question arises, how could Ron, a black man, have possibly embedded himself in a white supremacist organisation? What happened when he had to meet these people in the flesh? “I called my friend Chuck,” Ron says.

It was never actually intended to be a sting, explains Ron. The police were worried at the time, and wanted to find out more about Klan activities, so Ron did some homework. “When I saw that ad in the newspaper I wrote back, thinking they’d just send me some pamphlets.” Instead, Ken O’Dell called him directly, identifying himself as the local organiser of “The Cause”. Ron hadn’t been prepared for that phone call, but he’d had the presence of mind to include in his letter an untraceable number which fed directly into the police department. That said, he also made two howling errors: he’d signed his letter to the KKK ad with his own name, and “I broke the most basic rule of all and that was going into a case without a plan of operation.” Talking to Ken that first time, Ron improvised as best he could: “My sister was recently involved with a nigger,” Ron angrily told Ken during the phone call, “and every time I think about him putting his filthy black hands on her pure white body I get disgusted and sick to my stomach.” “You’re the kind of person we’re looking for,” said Ken. “When can we meet?”

Chuck now enters, stage left. Ron decided there needed to be two Ron Stallworths: the black version (himself) who would continue written correspondence and manage the untraceable phone line; and the white version, Chuck, a friend of Ron’s who worked in the narcotics department, who would deal with the KKK’s cloak-and-dagger meet-ups when they arose.

Chuck was game but senior staff were against the idea, arguing: “They’ll know you’re a black man from the sound of your voice.” Ron explains how US law enforcement was at the time somewhat confused between its own prejudices and its determination to crack down on race hate crimes. It didn’t want a replay of the riots of the late 1960s and early 70s. White supremacist groups and, at the other extreme, Black Panthers, covertly or not, advocated armed combat. In Denver, the Klan had recently burned several 14ft crosses in strategic locations; a black man escorting a white woman to the cinema had been shot dead; antisemitism was on the rise. African-Americans did not take well to Ron joining the police force, he says: “I was too ‘white’, too ‘blue’”; his white colleagues, meanwhile, gawped at his Afro.

“I didn’t care, and I still don’t care what anyone thought,” says Ron. He charmed and bulldozed the powers-that-be that not every black person “shucked and jived”, or engaged in criminal behaviour. “They harboured no bigotry against me personally, but hadn’t reached the point where they could see past their stereotypes.”

The grocery and bicycle store on Main Street, Colorado Springs, are no longer there, but the Kwik Inn is still standing. A 1950s diner, it looks exactly as it did when Ken chose it as the location for his first meeting with Ron. He was to turn up there at 7pm where he’d be met by a skinny, cigar-smoking white man with a Fu Manchu moustache, who would take him to a secret location to discuss Ron’s eligibility for membership of the Klan. Chuck, the “white Ron”, set off, wired up, with the black Ron and a second narcotics investigator called Jimmy trailing his movements from a surveillance vehicle.

A mile or so later, the skinny cigar smoker pulled up outside a dive bar that the local Klan used as its recruitment centre. Ken was inside with another man, and a Klan membership form for Ron. Ken was 28, short and stocky – an army man. The military base, Fort Carson, was a short drive away. Ken boasted that, under him, the Crusader, the Klan newspaper, was now widely circulating in Colorado prisons and military staff were secretly joining in droves. What is certainly true is that many white military men resented the new black presence among their officers – a perfect opportunity for the Klan to widen its base. Ken was satisfied that Ron didn’t have “any Jew in him”, and explained that membership cost $10, but new recruits had to pay extra for a robe and cloak.

It was often, says Ron, very hard not to burst out laughing at the credulity and the petty officiousness of the Klan members. Back at the police station, he recalls, “My sergeant would sometimes be laughing so hard he’d have to excuse himself from the room.”

Only once did any members of the Klan get suspicious. “Chuck had been to a meeting with the Klan members and there had been something I wanted to follow up on so, a couple of hours after Chuck left the meeting, I called Ken. He immediately said: ‘What’s wrong with your voice?’ So I coughed a bit and said I had a sinus infection. Ken proceeded to prescribe me a remedy. He said: ‘I get those all the time.’”

The deeper the investigation probed, the less laughable the inept Klansmen became. Soon after that first meeting, Ken called Ron to invite him to his house. Ken and a small group of “losers” (Ron’s words) were assembled in the living room, including the group’s second-in-command, its treasurer and a bodyguard. Plans to burn four 17ft crosses were discussed and finalised: everyone in the group agreed it would be a deeply moving religious experience. Publicly, the Klan were against violence. Ken gave White Ron the tour of his own personal arsenal, which included 13 shotguns, plus the weapons he carried in his vehicles.

As special guests at his next rendezvous, Ken invited the leaders of a powerful Nazi survivalist group, Posse Comitatus. Together they watched a screening of a nationalist film and discussed collaborating on terrorist activities.

David Duke, the white supremacist politician and a holocaust denier, is still an influential person in American political life. In May, he accused Trump of “stealing” his Build The Wall slogan, which he’d coined in the 1970s. At the time of Ron’s investigation, Duke was the Klan’s newly appointed leader or Grand Wizard: a clean-cut and reasonable-seeming man “He was a Dr Jekyll but he’d turn into Mr Hyde in private conversations,” remembers Ron. In the pivotal breakthrough in the case, Ron was put on to Duke to check the status of his membership card.

Duke is a PR man to his core. In the view of the Far Right, his greatest achievement was conferring respectability on the KKK, banning his members from wearing hoods and robes in public, and aligning “The Cause” with fundamental Christianity and dissatisfaction with the government. “Duke was a con artist,” says Ron. “His appearance was that of an all-American boy every mother would want as a prom date for her daughter.” “Racial Purity Is America’s Security” is the slogan he used when he ran for Louisiana state senator – as a Democrat.

Ron established a friendly relationship with Duke over the phone. He describes him as “a very pleasant conversationalist”. Duke presided over Chuck’s solemn candle-lit naturalisation ceremony. “I laugh all the time about our investigation, especially about making a fool of David Duke, who likes to think I don’t have the intelligence of an ape because he thinks I’m genetically inferior,” says Ron. “How I conned the Grand Wizard, David Duke, and his coterie of followers… It has defined me in ways I never could have imagined.”

As fascinating as Ron’s story is, what did he actually achieve? The sting never resulted in any arrests and when, months in, the Klan unexpectedly nominated Ron as its local group leader, he was forced to shut down the investigation. If the story got out, Colorado police worried it would be misconstrued: in the 1920s, Denver’s head of police was a Klansman. But through their work, Chuck and Ron had foiled a Neo-Nazi plot to nail-bomb a gay bar and identified seven Klansman army personnel. They’d discovered where the local Klan kept its money. Ron also uncovered intelligence regarding violent plots among black extremists.

In mid-1979, the investigation was terminated. A year later Duke left the Klan to form the National Association for the Advancement of White People. Ron followed his career in law enforcement to Wyoming, Arizona and Utah, specialising in gangs. When he retired in 2006, he gave that bombshell newspaper interview. The FBI called him after the piece went viral: Ron’s name, picture and alleged home address had been published on white supremacist websites. “After that, I started carrying a gun again,” he tells me. Was he frightened? “I have never had a fear of white people. As a child, if anyone called me a nigger, my mother would say: ‘I hope you whipped his ass!’”

Ron says that in the 1970s white extremism was considered weird and fanatical, but he’s shocked that it has now become mainstream. “If someone had predicted it back then, I’d have said they were out of their mind,” he says. “We’ve always had people in public office who were more middle ground. They work together. Trump, who is a billionaire, an ‘educated man’, essentially has the same message as Duke had on the phone. The very fact he equates Neo-Nazis [after Charlottesville] as ‘very fine people…’”

As for the film, he says: “Spike’s take on the book is pretty accurate,” Ron says. “I got a lot of joy from telling my story.” I can hear him smiling on the other end of the phone.

This article was amended on 25 July 2018 to correct the title of a Utah newspaper: Deseret News, not Desert News.

Black Klansman by Ron Stallworth (£7.99, Arrow) will be published on 29 July. Spike Lee’s film BlacKkKlansman is released on 24 August. Special nationwide screenings and Live Satellite Q&A with Spike Lee on is on 20 August (blackkklansmanscreening.co.uk). Read our interview with Spike Lee in the Observer New Review on Sunday 29 July