BEVERLY — In the 11 seconds after Patrolman Stuart Merry pulled out onto Cabot Street with his orange Big Gulp, his cruiser accelerated from 8 to 56 miles an hour before crashing into a parked car where Bonney Burns was sitting.

Burns, 61, was killed on that cold, sunny morning of Jan. 20, 2007.

And jurors yesterday began hearing the evidence that will help them decide why: Was Merry, 41, negligent that morning, distracted by something and not paying attention as his cruiser sped up and then veered across Cabot Street at a bend? Or was he suffering from some sort of medical problem that made him incapable of controlling the cruiser?

Merry's trial on a charge of negligent motor vehicle homicide got underway yesterday morning in Peabody District Court, where a jury of seven women and one man heard first from eyewitnesses and then from a series of police officers who responded to the crash scene or saw him before the crash.

And at the end of the day, they heard a prosecutor read a statement Merry gave to a state police investigator. In the statement, Merry claimed not to recall what happened seconds before the crash — and he described the location of a makeshift cup holder that had been mounted to a heating vent in the cruiser.

If convicted of the misdemeanor charge, he could face up to 21/2 years in jail and would lose his driver's license for 10 years. Merry has been on paid administrative leave since the crash.

For months after the crash, Merry's legal team — and his colleagues in the Beverly Police Department — attributed the crash to a sudden acceleration problem in the Ford Crown Victoria cruiser he was driving. They pointed to reports written by fellow officers about the cars suddenly taking off.

But after a clerk's show-cause hearing in the case, the defense appeared to back away from that theory — and has apparently abandoned it entirely.

Instead, defense lawyer Neil Rossman suggested to jurors that Merry's failure to apply the brakes or try to avoid the collision "is consistent with an operator who had a medical emergency."

"There's no way any driver in control of his or her faculties could be negligent for 11.2 seconds," Rossman told jurors yesterday.

Prosecutor Nicholas Walsh countered that jurors will see Merry's medical records from immediately after the crash, which show no pre-existing medical condition to explain why Merry would have been unable to control the car.

He pointed to witnesses who said they saw the cruiser speeding in the seconds before the crash — a father and his young son walking; Burns' upstairs neighbor, who was heading north on Cabot Street; and another woman who was heading south.

Heather Swan, 33, was living in the third-floor apartment at 361 Cabot St., just upstairs from Burns, and was headed home from a trip to the supermarket when she spotted her neighbor's car parked on Cabot Street. That usually meant Burns, who had a bad back, was bringing in groceries.

Then, she said, she saw a police cruiser make a "hard left" and collide with Burns' car.

As she testified, she was shown photos of a crumpled police cruiser, nearly perpendicular to Burns' sedan, which was pushed onto the sidewalk and crushed against a retaining wall.

Another witness, Amy Munoz, 23, was on her way to a dentist appointment and stopped at a drugstore to buy a magazine. She pulled out of the parking lot just behind Merry, who was heading south.

"I saw him turn very quickly, almost like he was making a U-turn, and I saw him hit the car," Munoz said.

She said she checked on both drivers and noticed Merry with his face between his arms, moaning.

Frederick Blake Kelsey, 38, was walking back from Dunkin' Donuts with his 4-year-old son when they heard the roar of a car accelerating behind them. Kelsey turned to look and said he was surprised to see that the car appeared to be driverless.

"I do not recall seeing a driver behind the wheel," he said. As the cruiser passed them, he said, it failed to negotiate the curve and barreled straight into Burns' car. He said he did not notice the car swerving or turning, however.

None of the witnesses saw the cruiser's lights or heard a siren before the crash. But afterward, Kelsey and several police officers testified that the lights had been activated.

Merry's torso was leaning over a center console that houses a bank of switches that control the lights and siren.

One of his fellow officers later testified that he went into the cruiser after Merry was taken out and turned off the lights.

While the eyewitnesses said Merry appeared to be unresponsive and having trouble breathing, fellow officers said he was semiconscious but unaware of what had happened or what was going on around him and not responding to them when they called his name.

Sgt. Joseph Shairs testified that Merry was turning blue from a lack of oxygen. He said that he and Sgt. Michael Cassola helped Merry sit up in the cruiser and gave him oxygen.

Cassola testified that Merry was "unconscious" and "out of it," but that he was also pushing himself off the seat. Shairs described Merry as "slightly" combative and responding inappropriately or not at all to questions.

Two other officers who testified, Patrolmen Daniel Skerry and David Costa, said Merry seemed normal that morning.

Costa, who was once Merry's partner, testified, "I used to make fun of him; I told him he drove like an old lady."

Walsh and another prosecutor, James Burbine, re-created the questioning of Merry by state police Sgt. Dennis Marks, who was not available.

The two prosecutors read from a transcript of that questioning, Burbine playing the role of Merry.

Just before the crash, Merry had stopped at a 7-Eleven to get a soda, which he put into the makeshift cup holder, then pulled out onto Cabot Street. He crossed the railroad tracks and passed Cornerstone Liquors.

"I remember going up the hill, taking the bend," he told Marks. "That's the last I remember."

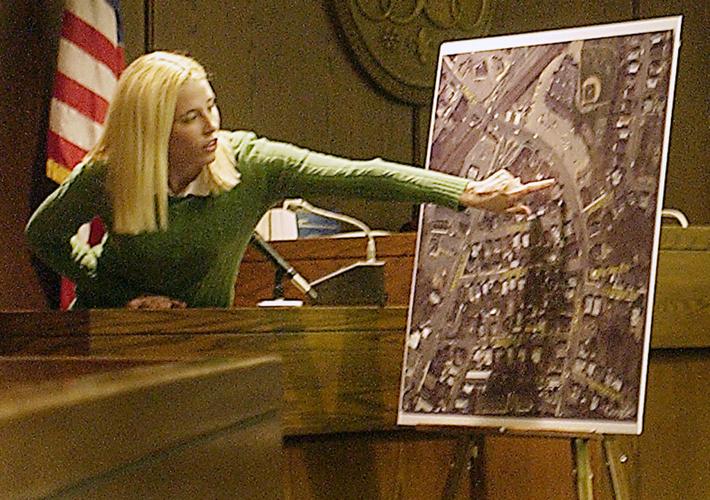

Jurors will return to court this morning to hear from a state trooper who conducted an accident reconstruction and who used so-called black-box data from two computers inside the car to determine the cruiser's dramatic acceleration. The gas pedal was to the floor, the throttle was at 100 percent, and only a brief tap of the brakes was evident, she is expected to testify.

The jury is also expected to visit the scene of the crash sometime late this morning.