The Monster of Glamis

The secret of Glamis Castle—a concealed room, a hidden heir—was one of the great talking points of the 19th century. But will the mystery ever be resolved?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120210095106glamis-castle-monster.jpg)

“If you could even guess the nature of this castle’s secret,” said Claude Bowes-Lyon, 13th Earl of Strathmore, “you would get down on your knees and thank God it was not yours.”

That awful secret was once the talk of Europe. From perhaps the 1840s until 1905, the Earl’s ancestral seat at Glamis Castle, in the Scottish lowlands, was home to a “mystery of mysteries”—an enigma that involved a hidden room, a secret passage, solemn initiations, scandal, and shadowy figures glimpsed by night on castle battlements.

The conundrum engaged two generations of high society until, soon after 1900, the secret itself was lost. One version of the story holds that it was so terrible that the 13th Earl’s heir flatly refused to have it revealed to him. Yet the mystery of Glamis (pronounced “Glarms”) remains, kept alive by its association with royalty (the heir was grandfather to Elizabeth II) and by the fact that at least some members of the Bowes-Lyon family insisted it was real.

Sir Walter Scott, the popular 19th-century novelist, was the first man to tell of the 'secret' of Glamis.

Glamis Castle is mentioned by Shakespeare—Macbeth, that most cursed of characters, was Thane of Glamis—and in 1034 the Scottish King Malcolm II died there, perhaps murdered. But the present castle was constructed only in the 15th century, around a central tower whose walls are, in places, 16 feet thick. Glamis has been the family seat of the Strathmore Earls since then, but by the late 18th century it lay largely empty, its owners preferring to live somewhere less drafty, less isolated and less melancholy.

In their absence, Glamis was left in the care of a factor, or estate manager, and it was to this factor that a young Walter Scott applied in 1790 to spend a night in one of its rooms. Scott became the first of several writers to note the castle’s oppressive atmosphere. “I must own,” he wrote in an account published in 1830, “as I heard door after door shut, after my conductor had retired, I began to consider myself as too far from the living and somewhat too near to the dead.” What was more, the great novelist added, Glamis was said to hide a secret room—a useful addition to any residence in 15th-century Scotland, where violence was seldom far away. Its location was known only to the Earl, his factor and his heir.

In one sense, however, the most interesting thing about Scott’s account is what it doesn’t say. The novelist wrote nothing to suggest that the castle’s hidden chamber had an occupant. Yet, within half a century of his visit, it had begun to be rumored that the room concealed an unknown captive—a prisoner who had been held there all his life.

The first reports of Glamis’ unknown prisoner appear to date to the 1840s. According to a correspondent to the journal Notes & Queries, writing in 1908,

The mystery was told to the present writer some 60 years ago, when he was a boy, and it made a great impression on him. The story was, and is, that in the Castle of Glamis is a secret chamber. In this chamber is confined a monster, who is the rightful heir to the title and property, but who is so unpresentable that it is necessary to keep him out of sight and out of possession.

Just who this elusive captive might be was the subject of considerable speculation. It was generally believed that he must have been a member of the Bowes-Lyon family, and commonly suggested that he was the first-born of the 11th Earl, or the heir of that Earl’s son, Lord Glamis. Supporters of the theory point to Douglas’s Scots Peerage, which records that after Lord Glamis married Charlotte Grimstead in 1820, their first child was “a son, born and died 21 October 1821.” What if that son, the thinking goes, did not die so quickly and conveniently? What if lived on, hidden away somewhere inside the castle?

Several Victorian-era guests at Glamis made it their business to pry into the Earls’ supposed secret, and by the second half of the century it was frequently reported that a child had been born to the Bowes-Lyonses horribly deformed—whole in mind, perhaps, but so hideously twisted in body that he could never be allowed to inherit the title. This may sound like the plot of some Gothic novel, but believers in the theory point out that the family has dealt with some of its members in ways that outsiders might consider harsh. After the First World War, Katherine and Nerissa Bowes-Lyon, both cousins of the present queen, were born mentally disabled. Both spent their lives locked away in homes and hospitals, ignored by their family.

What this “Monster of Glamis” might have looked like has been the subject of debate. There are tales of strange shadows seen on battlements in a part of the castle known as “the Mad Earl’s Walk.” A story dating to about 1865 says that a workman at the castle unexpectedly came upon a door that opened into a long passage. Venturing in, the man saw “something” at the far end of the corridor, and—on reporting the circumstances to the clerk of works—was pressingly encouraged to emigrate to Australia, his passage paid by an anxious Earl. Other 19th-century accounts referred to the Monster as “a human toad.”

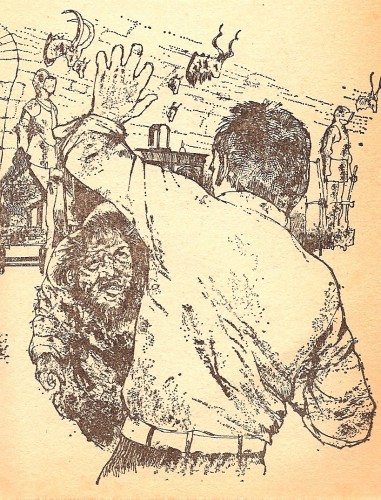

An artist's depiction of the Monster of Glamis, based on accounts given to James Wentworth-Day by members of the Bowes-Lyon family.

The only detailed description emerged early in the 1960s, when the writer James Wentworth-Day spent time at Glamis while writing a history of the Bowes-Lyon family. From the then-Earl and his relatives, Wentworth-Day heard the legend that “a monster was born into the family. He was the heir—a creature fearful to behold. It was impossible to allow this deformed caricature of humanity to be seen—even by their friends.… His chest an enormous barrel, hairy as a doormat, his head ran straight into his shoulders and his arms and legs were toylike.” But “however warped and twisted his body, the child had to be reared to manhood,” kept safe and occasionally exercised. That job was given to the factor.

If Glamis really does have a secret chamber, its location remains a mystery. Estate papers record the construction of one such hidey-hole adjacent to the charter room in the base of the tower, but others probably exist. One aristocratic guest, Lord Ernest Hamilton, wrote of discovering a passage concealed beneath “a trapdoor in the floor of the Blue Room dressing room,” while other sources suggest the chapel as a likely location. And the New York Sun reported in 1904:

On one occasion a young doctor, who was staying in the castle professionally, found on returning to his bedroom that the carpet had been taken up and relayed. He noted that the mark of the carpet was different at one end of the room. By moving the furniture and raising the carpet, he laid bare a trap door, which he forced open and found himself in a passage. This passage ended in a cement wall. The cement was still soft, leaving the impress of a finger. He returned to his room—and next morning received a cheque for his services with the intimation that the carriage was ready to take him to the station for the first train.

Not all accounts of the Glamis mystery are so anonymous. Sir Horace Rumbold, a British diplomat who first visited the castle in 1877, wrote of the frustration felt by successive Countesses, who were denied all knowledge of the secret. He told of an event that took place in 1850, when the 12th Earl’s wife asked her guests to aid her in a hunt while her husband was away.

The guests began by reasoning that the room probably had a window. Then, “the coast being clear,” Rumbold wrote, “somebody hit upon the ingenious device of opening the windows all over the castle, and hanging out of each of them a sheet, or towel, or pocket handkerchief.” Soon “innumerable white signals were…fluttering in the summer breeze, when Lord Strathmore unexpectedly returned.”

The Earl, Rumbold added, bitterly upbraided his wife and quickly divorced her. It is true that the marriage ended, and that the countess ended her unhappy life in Italy, but the results of her experiment remain disputed. Some accounts of the incident suggest that one tightly locked window in the tower remained unmarked by a towel; others say four.

The 12th Earl, in Rumbold’s account, was a “heedless man of the world, with few prejudices and possibly still fewer beliefs.” His heir and that heir’s son, though, were very much more more sober characters. This change was popularly attributed to their initiation into the family secret, which was thought to occur on the heir’s 21st birthday.

“It is related,” Rumbold c0ntinued, “that on his death bed told his brother that he must now endeavour to ‘pray down’ the sinister influence he himself had in vain tried to ‘laugh down,’ and which for so many years had darkened the family history.” Again, there is at least some evidence that this is what occurred. One of the first orders given by the 13th Earl was for the family chapel to be restored. It was solemnly rededicated in 1866, and shortly thereafter, according to the Penny Illustrated Paper, “a guest who had been staying at the castle, leaving early in the morning passed the little private chapel. There he saw kneeling in prayer at the altar his host, still dressed in the evening clothes which he had worn overnight.”

Accounts of Claude Bowes-Lyon and his children vary sharply. Ernest Hamilton remembered a boisterous, musical family, forever engaged in pranks and theatricals. But other visitors recalled a different Earl. According to the society gossip Augustus Hare, “only Lord Strathmore himself has an ever-sad look,” and it is to Hare that we owe another anecdote suggesting that, whatever the secret of the castle was, Claude thought it so terrible that it placed him beyond all normal aid:

The Bishop of Brechin, who was a great friend of the house, felt this strange sadness so deeply that he went to Lord Strathmore and said how, having heard of this strange secret which oppressed him, he could not help entreating him to make use of his services as an ecclesiastic.… Lord Strathmore was deeply moved. He said he thanked him, but that in his most unfortunate position, no one could ever help him.

Virginia Gabriel, whose long stay at Glamis in 1870 produced many of the best-known accounts of the castle's mystery.

Yet another visitor to Glamis was Virginia Gabriel, a singer who, according to her niece, returned from a long stay in 1870 “full of the mysteries, which she said had greatly increased since the death of the previous owner.” It is to this visit that we owe a strange reminiscence of the Glamis factor, Andrew Ralston—a dour, hard-headed man who, Gabriel reported, refused ever to spend a night in the castle. During her stay, a sudden snowstorm one evening blanketed the estate with drifts several feet deep. The Earl begged Ralston to take a spare room, but the factor refused, instead rousing every servant in the house to have them dig a path to his home a mile away. Gabriel also recorded an ominous conversation that she had with the Earl’s wife:

Lady Strathmore once confessed to Mr Ralston her great anxiety to unravel the mystery. He looked earnestly at her and said very gravely: ‘Lady Strathmore, it is fortunate that you do not know it, and can never know it, for if you did, you would not be a happy woman.’ Such a speech from such a man is certainly uncanny.

What drove Victorian society to distraction about all this was the endless discretion of the Glamis Earls, who might have provided a solution to the mystery. Charles Dickens’ weekly, All the Year Round, made precisely this point in 1880, when speculation was at its height, noting that as each new Earl succeeded to the title

there is generally much talk of the old story being exploded at last. Gay gallants in lace ruffles, beaus, bucks, bloods and dandies have, until their twenty-first birthdays, made light of the family mystery, and some have gone so far as to make after-dinner promises to tell the whole stupid story in the smoking-room at night.… This promise has been made more than once.… It has been pledged in burgundy and Tokay, in Laffite and champagne, in steaming toddy and in cooling lemon-squash. But it has never been kept.

Claude Bowes-Lyon, 13th Earl of Strathmore, was widely believed to find Glamis's "mystery" a terrible burden. "I have been into the room," Gabriel reported he had told his wife. "I have heard the secret, and if you wish to please me you will never mention the subject again."

Rumbold, too, had something to say about this. His information was that Earl Claude’s heir noted the terrible change that came over his father after he was told the family secret, and declined to be initiated himself. At this point, it would appear, the family lawyer was also in possession of the secret, having been enlightened in order to deal with the emigrating workman a few years earlier. “On being told,” Rumbold recorded, “that the time had come to for him to be initiated… is said to have inquired whether that secret was not in the safe-keeping of three persons, as prescribed.… On this being admitted, he had then replied that his immediate initiation not being indispensable, he preferred to wait until it should become so.”

It may have been then that Glamis’s secret began to pass from human knowledge; it may have been later. The 16th Earl, speaking to James Wentworth-Day in the 1960s, insisted that he knew “not a thing…. It may have died with my father, or with my brother, who was killed in the war.”

At the time, it was generally assumed that the mystery was not passed down to further generations because there was no longer any need for it; the Monster had died, and hence the scandal was at an end. When—or if—that happened, though, remains uncertain. The New York Times published a story as early as 1882 suggesting that “it is now believed that the mystery has been in part solved, and that the room contained some person who died a week or two ago at a very advanced age.” Other accounts suggest a death took place around 1904, around the time the 13th Earl passed on. Soon afterwards, the New York Tribune reported, “Glamis castle is to let, at a very high rent…. The fact that the new Earl of Strathmore should be willing to lease his ancestral historic home suggests that the celebrated mystery in connection with this castle…is now at an end, and the necessity of keeping secret and secluded one or more chambers…no longer exists.”

Rose Bowes-Lyon, Queen Elizabeth II's aunt, testified to her family's reluctance to discuss the mystery.

Was the Monster of Glamis ever more than mere gossip? The story is outlandish, and there are other legends of hidden rooms and nervous heirs, which strongly suggests that it was no more than a fable. At least one well-placed witness evidently suspected that the family spun tall tales themselves: David Lindsay, the urbane Earl of Crawford, visited Glamis in 1905 and noted in his diary that “The Lyons talk freely about ghosts and invent stories to suit the idiosyncracies of each guest.” Added Lindsay: “As to the alleged secret, I soon fathomed the mystery. The secret is ‘that there is no secret.’”

Against that, though, is the evidence that many members of the Bowes-Lyon family took the mystery very seriously. The last word goes to Rose, Lady Granville, another of Wentworth-Day’s informants and aunt to Elizabeth II. She had been born in the castle, and, asked what she knew of the story, she “looked serious, was silent for a moment, then said: ‘We were never allowed to talk about it when we were children. Our parents forbade us ever to discuss the matter or ask any questions about it. My father and grandfather refused absolutely to discuss it.’ ”

Sources

All the Year Round, 25 December 1880; The Crawford Papers: The Journals of David Lindsay, Twenty-Seventh Earl of Crawford… during the years 1892-1940. Manchester: MUP, 1984; Douglas’s Peerage of Scotland; Ernest Hamilton, Old Days & New. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1923; Augustus Hare, The Story of My Life London, 6 volumes: George Allen, 1896-1900; New York Sun 21 February 1904; New York Times, 17 April 1882; New York Tribune, 22 June 1904; Notes & Queries, 1884, 1901, 1908; The Queen, December 1964; Penny Illustrated Paper 30 September 1905; Horace Rumbold, Recollections of a Diplomatist. London: Arnold, 1902; Walter Scott, Letters on Witchcraft and Demonology. London: John Murray, 1830; AMW Stirling, Life’s Little Day. London: Thornton Butterworth, 1924; James Wentworth-Day, The Queen Mother’s Family Story. London: Robert Hale, 1967.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)