[box type=”bio”] What to Learn from this Article?[/box]

Proper history and adequate investigations are a must for diagnosis. Early detection of Giant Cell Tumor helps in complete excision and return of full functions.

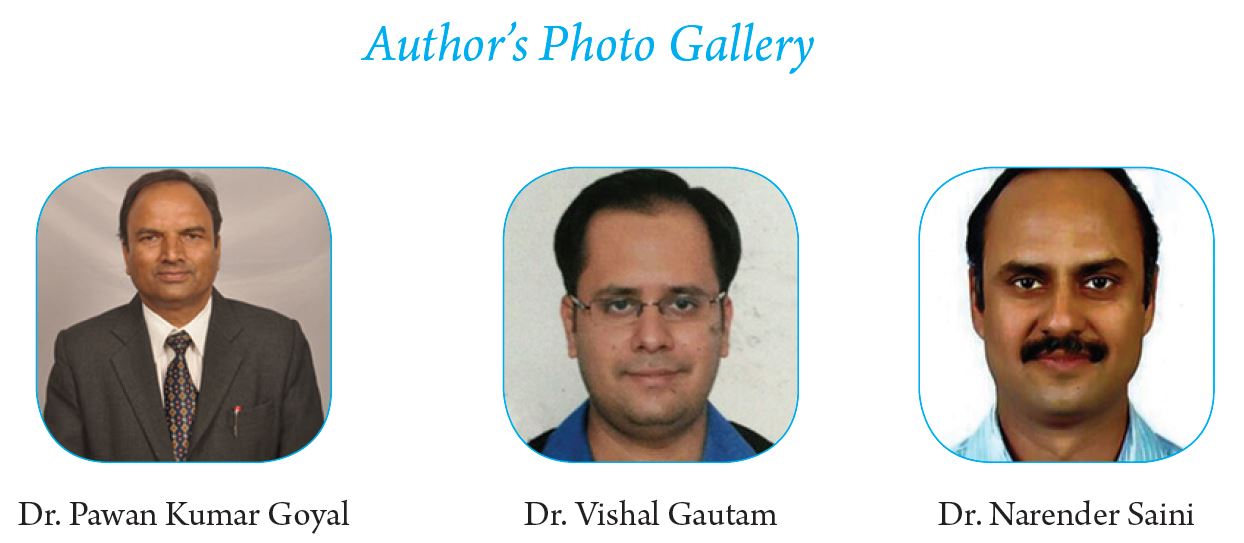

Case Report | Volume 6 | Issue 4 | JOCR September-October 2016 | Page 27-30 | Pawan Goyal, Vishal Gautam, Narender Saini, Yogesh Sharma. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.556

Authors: Pawan Goyal[1], Vishal Gautam[1], Narender Saini[1], Yogesh Sharma[1]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, SMS Medical College, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Vishal Gautam,

Flat No. 203 Second Floor, Plot No. 48, Gangwal Park, Jaipur ‑ 302 004, Rajasthan, India.

E‑mail: drvishigautam27@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: GCT is a bone tumor involving epiphyseal area of bone abutting the subchondral bone. Commonly found in long bones like proximal tibia and distal femur. We report a case of GCT of olecranon bone in a 23 year old male.

Case presentation: A 23 years old patient presented to our Out Patient Department with pain and mild swelling at the elbow from last 2-3 months. On examination it was seen that there was a moderate swelling at the tip of the Olecranon. The MRI reported a lytic lesion in the Olecranon but sparing the Coronoid process of the Ulna, the biopsy report confirmed that histologically it was a Giant cell tumor of the bone. Total excision of the tumor was done after lifting the aponeurosis of the triceps muscle . The area remaining after excision of the tumor was phenol cauterized and cleaned with Hydrogen peroxide solution. Triceps was reinserted on the remaining ulna. At follow up the radiographs showed adequate excision of the tumor. (Fig 4) The patient gained a full range of movement at the elbow and was functionally restored. There were no signs of any systemic spread of the tumor.

Conclusion: GCT though a very common bone tumor could be missed if present in atypical locations. Radiographically soap bubble appearance might not be present in every case and there could be multiple diagnosis for lytic lesion in bone. Proper investigations and histopathological examination is necessary for accurate diagnosis and further treatment planning. Early treatment helps in complete excision of tumor along with return of adequate function of the patient.

Keywords: GCT, Olecrenon, Bone

Introduction

There are very few reports of Giant cell tumor involving the Olecranon[1,2,3,4] his tumor despite being histologically benign has a high propensity of metastasis to the lungs[3] For this reason en block excision is the treatment of choice rather than curettage and bone grafting[5]. The aggressiveness of the tumor at this site can be judged from the case report of B.K.S Sanjay, O.N. Negi et al[1] where the patient died despite the fact that en block excision of the tumor was done after two failed attempts of curettage and bone grafting. Keeping in prospect the rarity of the tumor (2.94%)[6] and the fact that it warrants a timely and through excision. We present here a case of the GCT of the Olecranon with full functional follow up, which was managed by excision with preservation of the Coronoid process of the ulna and reinsertion of the Triceps aponeurosis to the remaining part of the Olecranon. There was no tumor recurrence at the local site or any signs of metastasis with a follow up of 5 years.

Case Report

A 23 years old patient presented to our Out Patient Department with pain and mild swelling at the elbow from last 2-3 months. The patient was a worker in Saudi Arabia, and has come on vacation, when he consulted us for his complains. On examination it was seen that there was a moderate swelling at the tip of the Olecranon, with no inflammatory signs, patient had a mild pain on working and at night, this was hindering with his daily activities. His radiograph and routine blood investigations were carried out. His radiograph revealed a lytic area in the Olecranon (Fig 1) more on the posterior aspect than the anterior. His routine blood investigations were within normal range. To have a better picture of the lesion and to confirm its nature an MRI of the elbow joint was done and a biopsy of the lesion was taken. The MRI reported a lytic lesion in the Olecranon but sparing the Coronoid process of the Ulna, the biopsy report confirmed that histologically it was a Giant cell tumor of the bone.

Once the confirmation of the diagnosis was made the treatment options were sought, it was seen from the published data that the tumor was rare, and had the propensity of metastasis to the lungs despite being benign histologically. Since the MRI showed that the Coronoid process of the Ulna was uninvolved, it was planned that total excision of the tumor will be done after lifting the aponeurosis of the triceps muscle, if adequate resection is done and Coronoid is found to be uninvolved intraoperatively, we will excise the tumor and reinsert the triceps on the remaining ulna. If in any case the there is suspicion of the tumor tissue present in the Coronoid process, the complete excision and future reconstruction for the elbow will be done with prosthetic replacement.

On the table while performing the excision of the tumor after lifting the triceps aponeurosis,(Fig 2) the Coronoid was found to be spared, the area remaining after excision of the tumor was phenol cauterized and cleaned with Hydrogen peroxide solution. Drill holes were made in the Ulna distal to the excised tumor and a V-Y plasty of the aponeurosis was done to bring the aponeurosis to the remaining bone, the tendon was sutured to the bone with Vicryl suture passed through the dill holes made. Wound was closed in layers.(Fig 3)

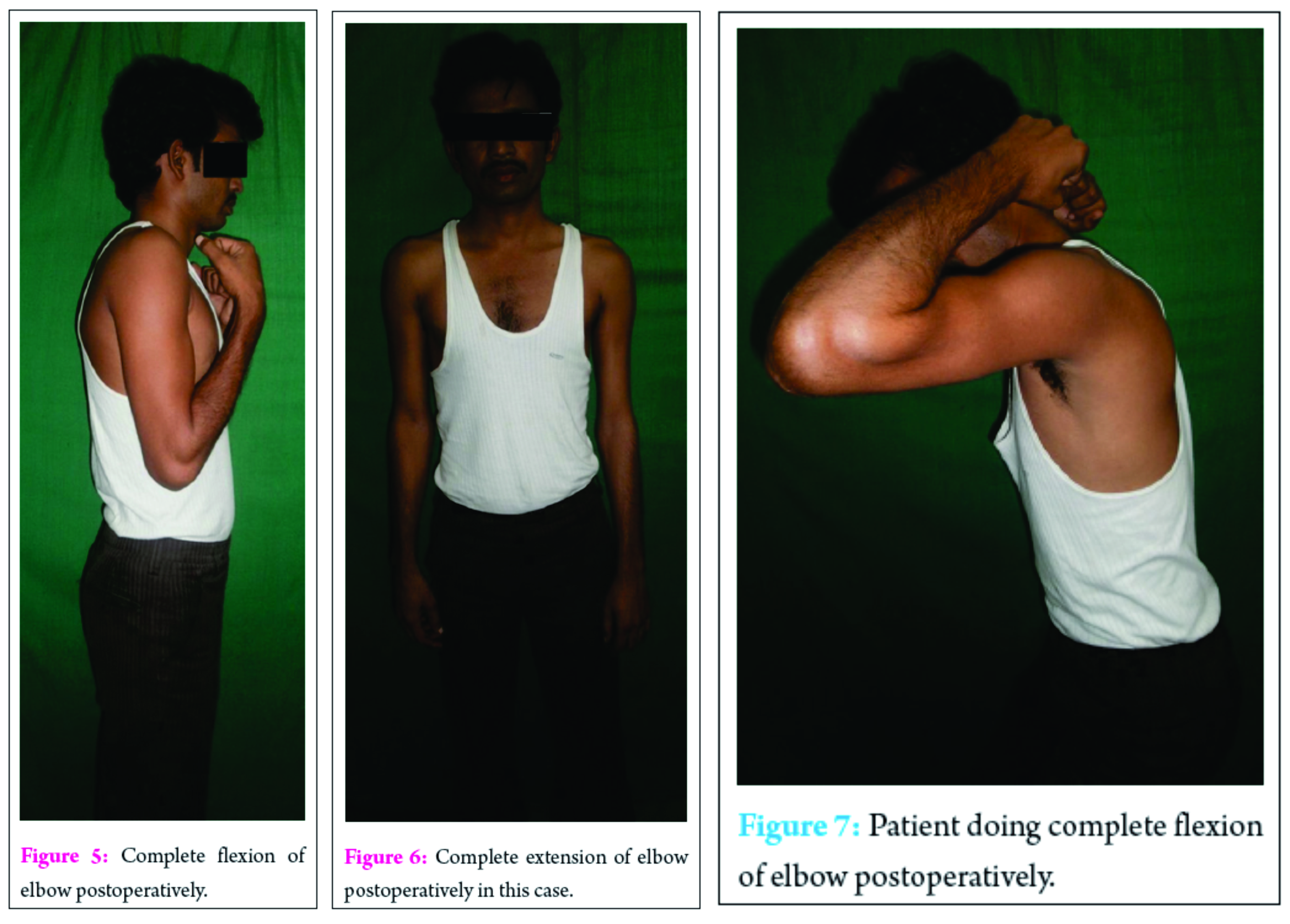

At follow up the radiographs showed adequate excision of the tumor. (Fig 4) The patient gained a full range of movement at the elbow,(Figs 5,6,7) and was functionally restored. At the follow up taken before the writing of this report which accounts for 5 years the radiographs showed no signs of recurrence. There were no signs of any systemic spread of the tumor.

Discussion

GCTs of bone present most often in the 3rd or 4th decade of life.[7] Most GCTs arise in metaphysical-epiphysical areas abutting the subchondral bone and are most commonly found in the distal femur, proximal tibia, and distal radius.[7,9] It can also be seen in the proximal femur, vertebral body, proximal fibula, hand, and wrist though less frequently.[7,9]

There has been many studies involving GCTs [8,13,14] in which a total number of 1,447 GCT of bone cases has been reported, but none of them were located in the olecranon. There has been one report of patient with multicentric GCTs involving the left proximal ulna from a 12 year retrospective study conducted at the Mayo Clinic Hoch, et al.,[15]. As per our best knowledge and pubmed index there has been 3 reported cases of solitary olecranon so far.[2,3,4]

The radiographic appearance of GCT is usually characteristic of the disease. However it was difficult to make a definitive conclusion in this case, although the plain films showed characteristic findings of GCT largely due to the rare location of the lesion, and the olecranon is a rare area for neoplasms to occur. There are only few diseases involving this anatomical region have been reported, including a ganglion cyst,[16] osteoid osteoma,[17] and metastasis.[18] However, the X Ray examination and histopathological examination clears the diagnosis.

Intralesional curettage along with local adjuvants, such as liquid nitrogen,[19] bone cement,[20] and hydrogen peroxide,[21] has been the preferred treatment for most cases of GCT of bone.[24] But Wide en bloc resection is known to provide the lowest recurrence rate.[22] Radiotherapy has also been used to treat GCT of bone and is mainly useful for treating difficult locations, such as the spine and sacrum.[23]

Conclsion

GCTs of bone represent approximately 5% of primary bone tumors in adults.[8] In addition, patients with GCTs of bone present most often in the 3rd or 4th decade of life.[5] Most GCTs arise in metaphysical-epiphysical areas and are most commonly found in the distal femur, proximal tibia, and distal radius.[5,9] Other less frequent sites include the proximal femur, vertebral bodies, distal tibia, proximal fibula, hand, and wrist.[5,9] In addition, GCTs occurring in the patella and great trochanter have been reported.[10,11,12]

Giant cell tumor of the bone occurring at the Olecranon is rare (2.94%)[7]. There are very few case reports on this, and those published, show high recurrence rate, despite excision. This paints a very gloomy scenario for the patients presented with this condition.

We planned to present this case report, as not only this rare tumor was excised in total, but good functional restoration was achieved, and there was no recurrence either local or systemic. This gives hope to the fact that early detection of GCT Olecranon not only aids complete excision and return of full function.

Clinical Message

GCT although a common bone tumor still can be missed if present in unusual locations. Proper history and adequate investigations are a must for its diagnosis. Early detection helps in complete excision and return of full functions.

References

1. B.K.S Sanjay, O.N. Negi and B.D Gupta; Giant cell tumor of the proximal end of Ulna- Arch Orthop Trauma Surg(1991)110: 208-209.

2. Bhalla R; Mathur S; Bhalla S; Giant Cell tumour of olecranon Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 1990 Jul; 24(2): 243-4

3. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. Multiple pulmonary metastasis from histologically benign giant cell tumor of the right radial olecranon1991 Aug; 29(8):1070-4.

4. Yang C, Gong Y, Liu J, Qi X. Rare GCT involvement of Olecrenon bone. J Res Med Sci, 2014 jun; 19(6): 574-6

5. Wyoscki RW, Soni E, Virkus WW. Is intralesional treatment of GCT of distal radius comparable to resection with respect to local control and functional outcome. Clin orthop Relat Res. 2015. 473(2): 706-715

6. Patond, KR and Badole, CM (1992) Giant cell tumour of olecranon. Indian Practitioner, 45 (7). p. 587.

7. Niu X, Zhang Q, Hao L, Ding Y, Li Y, Xu H, et al. Giant cell tumor of the extremity: Retrospective analysis of 621 Chinese patients from one institution. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:461–7.

8. Unni KK. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. Dahlin’s bone tumors: General aspect and data on 11087 cases; pp. 263–283.

9. Turcotte RE. Giant cell tumor of bone. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:35–51.

10. Agarwal S, Jain UK, Chandra T, Bansal GJ, Mishra US. Giant-cell tumors of the patella. Orthopedics.2002;25:749–51

11. Yoshida Y, Kojima T, Taniguchi M, Osaka S, Tokuhashi Y. Giant-cell tumor of the patella. Acta Med Okayama. 2012;66:73–6.

12. Resnick D, Kyriakos M, Greenway GD. Tumors and tumor-like lesions of bone: Imaging and pathology of specific lesions. In: Resnick D, editor. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunder; 1995. pp. 3628–3938.

13. Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am.1987;69:106–14.

14. Goldenberg RR, Campbell CJ, Bonfiglio M. Giant-cell tumor of bone. An analysis of two hundred and eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:619–64.

15. Hoch B, Inwards C, Sundaram M, Rosenberg AE. Multicentric giant cell tumor of bone. Clinicopathologic analysis of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1998–2008.

16. Zarezadeh A, Nourbakhsh M, Shemshaki H, Etemadifar MR, Mazoochian F. Intraosseous ganglion cyst of olecranon. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:581–4. [PMC free article]

17. Tounsi N, Trigui M, Ayadi K, Kallel S, Boudaouara Sallemi T, Keskes H. Osteoid osteoma of the olecranon. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2006;92:495–8.

18. Culleton S, de Sa E, Christakis M, Ford M, Zbieranowski I, Sinclair E, et al. Rare bone metastases of the olecranon. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1088–91.

19. Malawer MM, Bickels J, Meller I, Buch RG, Henshaw RM, Kollender Y. Cryosurgery in the treatment of giant cell tumor. A long-term followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999:176–88.

20. Bini SA, Gill K, Johnston JO. Giant cell tumor of bone. Curettage and cement reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995:245–50.

21. Nicholson NC, Ramp WK, Kneisl JS, Kaysinger KK. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits giant cell tumor and osteoblast metabolism in vitro. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998:250–60.

22. Pazionis TJ, Alradwan H, Deheshi BM, Turcotte R, Farrokyhar F, Ghert M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of En-Bloc vs Intralesional resection for giant cell tumor of bone of the distal radius. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:103–8.

23. Kriz J, Eich HT, Mücke R, Büntzel J, Müller RP, Bruns F, et al. German Cooperative Group on Radiotherapy for Benign Diseases (GCG-BD). Radiotherapy for giant cell tumors of the bone: A safe and effective treatment modality. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2069–73.

24. Cho HS, Park IH, Han I, Kang SC, Kim HS. Giant cell tumor of the femoral head and neck: Result of intralesional curettage. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1329–33.

| How to Cite This Article: Goyal P, Gautam V, Saini N, Sharma Y. Rare Giant Cell Tumor of Olecranon Bone!!!!. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2016 Sep-Oct;6(4): 27-30. Available from: https://www.jocr.co.in/wp/2016/10/10/2250-0685-556-fulltext/ |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com