Editor’s Note: Judy Melinek, MD, is a forensic pathologist who served as a medical examiner at the Manhattan Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for two years. She is the co-author of “Working Stiff” (Scribner). The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Judy Melinek: Medical examiners act as quality control over law enforcement agencies

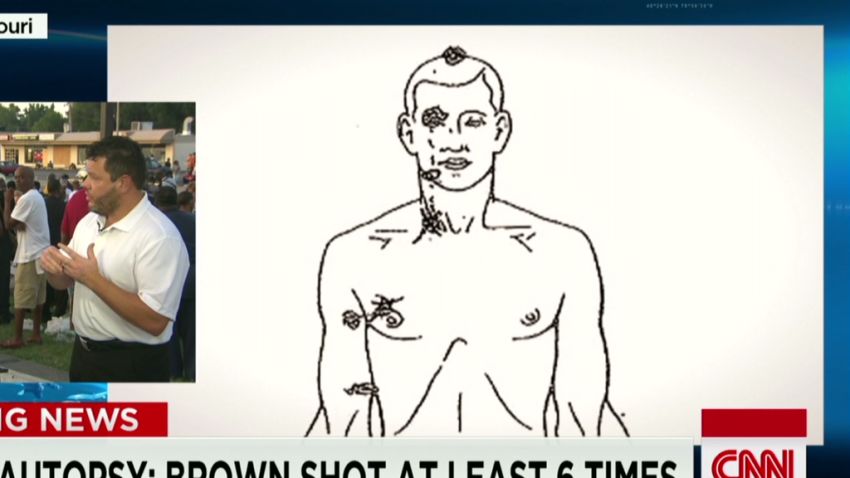

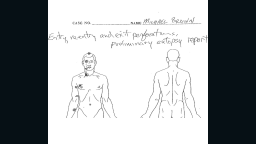

Melinek: Body diagram of Michael Brown suggests he was facing the officer, leaning forward

She says as doctors who perform the autopsy, medical examiners speak for the dead

Melinek: Public should trust medical examiners' report since they act independent

Michael Brown, Eric Garner and John Crawford all have one thing in common: It’s not just that they were unarmed men of color killed by police officers – it’s that the responsibility to investigate each of their deaths fell to a medical examiner.

We medical examiners investigate all homicides and violent deaths, and it is also part of our legal duty to investigate any death of a person under the control of, or in the custody of, a law enforcement agent.

I have worked as a medical examiner for 13 years in four large cities in the United States. Medical examiner offices are independent public agencies, and one of our responsibilities is to act as quality control over law enforcement agencies. The medical examiner is the final arbiter of whether a death was the direct result of an arrest, or, instead, the result of natural disease or an incidental event.

Medical examiner reports in most states are public records. We all deserve and should expect transparency in death investigation. The family of the deceased, the news media and anyone who asks for it can get a copy of the medical examiner’s or coroner’s autopsy report on any case that is not sealed as part of an active investigation.

Medical examiners are physicians, specialists in forensic pathology. We are professionally protective of our independence. We know that it is our duty and responsibility, as the doctors who perform the autopsy, to speak for the dead.

Unfortunately, in the wake of the death of a civilian at the hand of police officers, the public is often suspicious of the medical examiner.

Because the law requires a local government agency to perform the death investigation, people often assume that this agency falls under the jurisdiction or influence of the police. News reports critical of the amount of time the dead body was left at the scene, or the amount of time it takes to get a final autopsy report, exacerbate this distrust.

In St. Louis County, Missouri, where Michael Brown was autopsied, Dr. Mary Case, the chief medical examiner, is a board-certified forensic pathologist. She has years of experience and reports to the Health Department, not the police.

Brown’s official autopsy report was expedited and finalized on Monday. It was made available to the prosecuting attorney, who is now in charge of any release of information.

Why does a death scene investigation take so long? An outdoor death scene is a messy and complicated place. As soon as the person has been declared dead, the area has to be frozen in time to ensure that we, the public, can later learn what really happened there.

Crime scene photographers and trained evidence collection analysts have to “process the scene,” an hourslong procedure when done properly. The body, the position of any vehicles, the lighting, the height of adjacent structures –everything needs to be photographed from multiple angles.

In a shooting, crime scene investigators will have to measure and document the number and location of the casings, bullets and strike marks. If the evidence and its undisturbed location are not documented in this painstaking way, then criminal or civil complaints against the officer may not stand up in court.

But what about the autopsy report? Why does that take so long?

That’s because a competent job in the morgue, too, takes time. The work I do as a doctor in the autopsy suite after a typical gunshot wound homicide case may take three or four hours to complete, but after I leave the morgue, the report is not done.

I have to wait for the report from the toxicology lab, which usually takes a minimum of two weeks, and for histology slides to come back before I can examine them under a microscope. Any of these findings could impact the cause of death.

Even gunshot wounds cannot be interpreted in a vacuum.

As part of an investigation I have to try to figure out which defects in the body come from bullets entering, and which from their exit. Usually these wounds are distinctly different in appearance, but the more complex the body position of the deceased, the more complicated things get. Exit wounds in flesh pressed against the ground or against tight clothing can appear just like entrance wounds. An entrance wound inflicted through an intermediary target that deformed the bullet can look just like an exit wound. Sometimes I have to wait for the police reports or witness transcripts in to correctly interpret what I see on the body in the autopsy suite.

After the shooting in Ferguson, Michael Brown’s family hired Dr. Michael Baden, a former New York State Police medical examiner, to conduct a second autopsy, and the federal Department of Justice instructed the Armed Forces Medical Examiner to conduct a third.

What you can tell from a second or third autopsy is limited by autopsy artifact – changes to the evidence caused by the performance of the first autopsy.

In the course of the first, legally mandated autopsy, the forensic pathologist will have taken the organs out and sliced them apart for examination. The gunshot wounds will have been probed, and sometimes even cut into.

More importantly, any pathologist hired by the family, regardless of expertise, does not have access to the crime scene and other evidence. Even Baden, in the report he prepared for the Brown family, concluded that without the clothing, evidence or scene information, he had “too little information to forensically reconstruct the shooting.”

Why weren’t the St. Louis medical examiner’s autopsy findings made public immediately? Because releasing preliminary information when the investigation is still ongoing is premature and potentially inflammatory.

Already the results of Baden’s limited investigation are being used to support the contention that Brown was surrendering, and that the wounds were distant range, even though Baden himself said neither.

To a forensic pathologist, the body diagram Brown’s attorneys released tells a different story. The wound at the top of the head, the frontal wounds and angled right hand and arm wounds suggest that the victim was facing the officer, leaning forward with his right arm possibly extended in line with the gun’s barrel, and not above his head.

The image of a person standing upright with his hands in the air when he was shot does not appear compatible with the wounds documented on that diagram. Whether a forward-leaning position is a posture of attack or of surrender, however, is a matter of perspective.

From the perspective of a witness, it could appear that the leaning person is complying with the officer and getting down. From the perspective of the officer, he may appear to be coming at him. Partial evidence yields partial answers, and a rush to conclusions based on one isolated set of data from a second autopsy only raises more questions.

That is why it is so important to be patient and wait for all the scene information to come to light.

But “be patient and wait” is not a demand that anyone has the right to make on a family that has lost a loved one in a sudden and violent event. When I have been assigned to investigate an in-custody or officer-involved death, I will often call the family right away.

It’s important to me to reach out to them, to tell the people who are awaiting answers from me that I am qualified to do the job I am trained for; that I will hide nothing from them; that everything I do on their behalf will be part of the public record; and to give them some idea of how long the process might take.

When the report is finished, I meet with family members or their attorneys to discuss the findings and explain the medical diagnoses I have come to. This solemn conference takes place behind the scenes, months after the incident, and is never reported in the news media – but it is probably the most important part of my job.

As a doctor and a civil servant, I take my public role seriously. I strive to with all my ability, training and effort to answer any questions that person’s family may have. I know that others in my field strive with the same effort. It’s why we went into our field of medicine. We are servants of the public – not of the state, not of any single law firm, and not of the police.

Magazine: The Aftermath in Ferguson

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine