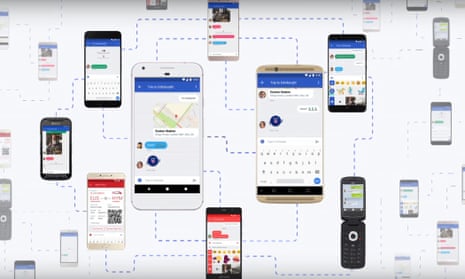

Google has unveiled a new messaging system, Chat, an attempt to replace SMS, unify Android’s various messaging services and beat Apple’s iMessage and Facebook’s WhatsApp with the help of mobile phone operators.

Unlike traditional texting, or SMS, most modern messaging services – such as Signal, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger or Apple’s iMessage – are so-called over-the-top (OTT) services, which circumvent the mobile phone operator by sending messages over the internet.

Google’s Chat is different. Users will not need to download another chat app or set up a new account. Instead of using OTT, it is based on rich communication services (RCS), a successor to SMS (short message standard), which has been used by people all over the world since 1992 and is still the fallback for most.

RCS has been in the works since 2007, steered by the GSMA mobile operator trade body. Various mobile phone operators have offered their own versions, typically called “advanced messaging” or similar, but they haven’t usually worked with the outside world.

With Chat, Google is unifying all the disparate versions of RCS under one interoperable standard that will work across networks, smartphones and operating systems. In doing so it hopes to take the surefire nature of SMS – anyone can send anyone else with a phone a message without them requiring a specific account or app – and bring it up-to-date with all the features modern chat demands.

“The GSMA has been working for almost a decade to foster broader adoption of RCS as a way to compete with third-party instant messaging and voice apps, but adoption over the years has been patchy,” said Raghu Gopal from CCS Insight. “If Google is able to establish its RCS client as a truly universal and usable client on Android devices globally, it may offer a way to reduce Facebook’s stranglehold on messaging services.

“Google and operators must come to the realisation that it’s getting late in the game, and it will take something special to establish RCS as a global standard.”

For mobile phone operators the move offers one last chance to ensure they do not end up simply as dumb data pipes providing the internet access through which others offer the services users demand, be it voice, video or text chat.

Anil Sabharwal, Google’s lead on the project, told the Verge: “We don’t believe in taking the approach that Apple does [with iMessage]. We are fundamentally an open ecosystem. We believe in working with partners. We believe in working with our OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] to be able to deliver a great experience.”

Google’s special sauce in this effort is the Android Messages app, the company’s default text message app, which is bundled with the majority of smartphones not made by Samsung or Apple. It is here Google hopes that, having corralled the 55 or so mobile phone operators, it can make the experience competitive with the likes of Apple’s iMessage or Facebook’s WhatsApp, with read receipts, photos, gifs, videos and all the trappings.

Users will be able to download the Android Messages app on to any Android device that doesn’t come with it, while Samsung and others that currently use their own SMS app have pledged support for Chat. The only major manufacturer not currently on board is Apple.

Unlike many of the best messaging services, RCS, and by extension Google’s Chat, is not and will not be encrypted. Despite being sent over the internet, it will be carried by mobile phone operators and therefore subject to all the traditional communications regulations of search and surveillance.

Q&AWhat are the pros and cons of encryption?

Show

Without encryption, everything sent over the internet – from credit card details to raunchy sexts – is readable by anyone who sits between you and the information's recipient. That includes your internet service provider, and all the other technical organisations between the two devices, but it also includes anyone else who has managed to insert themselves into the chain, from another person on the same insecure wireless network to a state surveillance agency in any country the data flows through.

With encryption, that data is scrambled in such a way that it can only be read by someone with the right key. While some older and clumsier methods of encryption have been broken, modern standards are generally considered unbreakable even by an attacker possessing a vast amount of computer power.

But while encryption can protect data that it is vital to keep secret (which is why the same technology that keeps the internet encrypted is used by militaries worldwide), it also frustrates efforts by law enforcement to eavesdrop on terrorists, criminals and spies.

That's particularly true for “end-to-end” encryption, where the two devices communicating are not a user and a company (who may be compelled to turn over the information once it has been decrypted), but two individual users.

For users, they’ll see their regular SMS experience be enhanced with RCS once their phone operator switches on support; when all else fails, the service will fall back to SMS so there will be no fear that the text of the message is not getting through.

Getting people to use Chat will certainly be a “tough ask”, says Kester Mann, mobile operator analyst for CCS Insight. He said: “The messaging space is a tough market to crack, but if the support of Google, the GSMA and leading operators isn’t enough to give it a chance, then I can’t see RCS taking off.”

Google’s previous efforts to produce an iMessage beater, of which there have been many, have fallen way short of the billions of users Facebook has across its WhatsApp and Messenger apps. But none of Google’s failed apps have had the backing of phone operators or been oriented around a system millions already use.

“Things have become convoluted in the mobile industry,” Gobal said, “with Google – a provider of several over-the-top services – working to promote a technology designed to tackle the threat of such services.”