Trump Abandons the Secret Code of 'Voter Fraud'

In telling an anecdote about alleged illegal votes, the president broke one of the unwritten rules of his party.

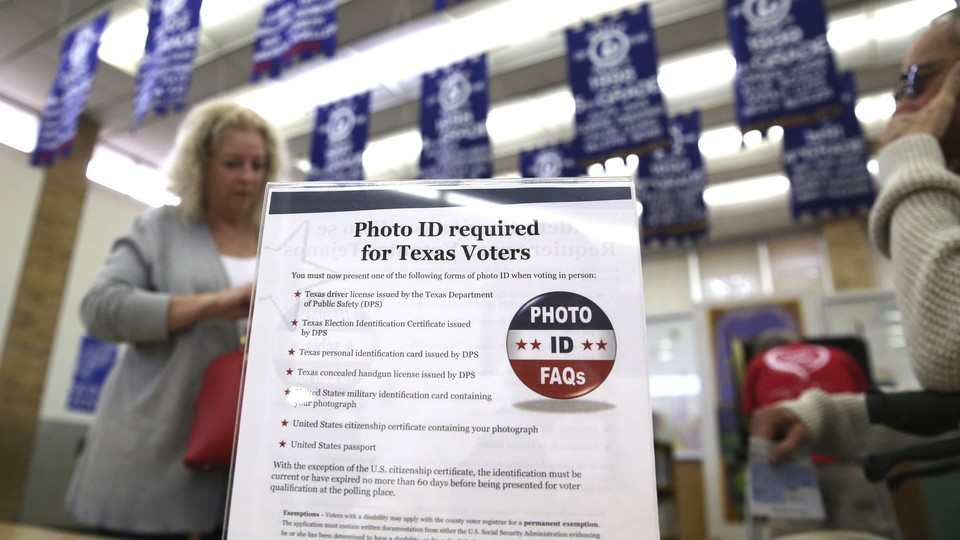

There’s a long history of using false claims of voter fraud to justify voter suppression. The practice has enjoyed a resurgence as of late, especially since the Supreme Court weakened federal oversight of voting laws in 2013, states like North Carolina and Texas have used trumped-up charges of voter fraud to implement voting laws and voter ID that have since been determined to be racially discriminatory.

These arguments exist within a tradition of using the specter of fraud to legally suppress votes on a racial basis. But for decades that tradition has relied on a wink and a nod—openly stating the discriminatory intent of laws that had the clear effect of disenfranchisement could be legally troublesome. The dog whistle is the key.

Just days into his term, President Donald Trump opened a new chapter in this long history, using the White House pulpit to make claims of massive voter fraud, and calling for changes in voting law. But in relaying an anecdote to congressional leaders intended to support his wholly unsubstantiated claims of millions of fraudulent votes from undocumented immigrants, Trump directly referred to the perceived ethnicity and nationality of suspect voters, instead of actual suspicions of fraudulent acts. In doing so, Trump broke the longstanding taboo of relying on racial insinuation to carry the implied threat of suppression.

The story, as reported in the New York Times, is bizarre. According to multiple sources, at a reception for House and Senate leaders Trump relayed a story meant to back his wild claims of fraud. That story involved German golfer Bernhard Langer. Three sources claim that Langer—a German citizen ineligible to vote in the United States—saw voter fraud by people he presumably believed to be undocumented immigrants, while trying to vote unsuccessfully himself. Another source contradicts this account, saying the story was relayed to Langer by a friend who was eligible to vote. But both accounts agree that Trump’s take from Langer was that a group of voters presumably of Latin American origin “did not look as if they should be allowed to vote,” as paraphrased by the newspaper. This was a bullhorn where we’d usually expect a more savvy dog-whistle.

As recently as the latest election cycle, the dog whistle was king. Republicans sounded the alarm early and often about reports of mass in-person voter fraud, despite no evidence that it exists. Republicans also rallied around the suspicion of undocumented immigrants registering to vote—again, a claim that remains unsubstantiated. Both of these claims that themselves invoke a certain threat of people of color and immigrants voting were used to justify voter suppression. Although the courts struck down some of the most egregious voting laws like North Carolina’s with its racial “surgical precision,” on the whole there were more voting restrictions in place in 2016 than in previous elections. Further, those laws were likely just a prelude to a slow dance of legal challenges that could seriously weaken the Voting Rights Act under a Trump administration.

Trump himself played along with the voter-fraud game on the campaign trail. Without evidence, he repeatedly claimed that there were millions of cases of voter fraud in favor of Democrats. He also implied that he might not accept the results of the election as legitimate based on that falsehood, though he later reversed that position after he won the election. But Trump did play by the rules of the dog-whistle game in using the cover of voter fraud to advocate for policies with histories and implications steeped in racism, such as poll-watching and intimidation in Democratic strongholds in neighborhoods of color.

Despite the apparent contradiction of claiming a legitimate victory and also maintaining a claim that millions of people cast votes illegally, Trump carried these claims into office, becoming the first president to demand an investigation into an election he won.

The genesis of these claims seems largely rooted in ego and perhaps a touch of distraction—Trump has been clearly rankled by losing the popular vote, and a focus on vilifying an out-group of minorities for tainting an election could serve as a badly-needed pressure valve amid swirling allegations of Russian interference on his behalf. But Trump has also tied these claims of voter fraud to the larger Republican aim of “strengthen[ing] up voting procedures.” In clarifying statements, White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer outlined that the investigation would focus on states and places that did not vote for Trump. How much distance is there between such an investigation and an imposition of draconian voter rules on communities of color? Historically, not much.

The game that Spicer is playing here relies on the things unsaid as much as the things said. In the wake of the Voting Rights Act and 52 years of changes in polite society since, naked voter suppression through outright violence and legal mechanisms openly targeted at black Americans has become anathema. The rabid segregationists of old were no longer tolerated, but the campaign to reduce the voting power of minorities—especially in the shadow of the old Jim Crow—continued apace, and picked up steam, respectability, and a sheen of intellectualism along the way. And the campaign continued so in a manner where intent no longer mattered.

After the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision rolled back federal oversight in southern elections for the first time since the civil-rights era, it’s no coincidence that many of those states moved immediately to restrict voting; and in North Carolina introduced the legislation on the same day as the decision. Emboldened by United States Chief Justice Roberts’s declaration in the Court’s opinion of that case that the country has changed since 1965, those states seemed intent on proving Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinion that the law’s protections themselves had been the source of those changes, and not an eradication of the underlying instinct to disenfranchise.

Armed with that decision, so long as they don’t mention race and stick to the script of things like “ballot integrity,” conservatives can likely convince friendly courts and a friendly Department of Justice that increasingly restrictive voting laws do not violate the 14th and 15th Amendments, despite the clear racially-disparate impact that things like voter ID laws do have. As long as they play the dog-whistle game, the road appears to be open.

Trump has since attempted to back up his claims with misrepresented data from a Pew study, as well as some unreleased reports from voting app VoteStand and its founder Gregg Phillips, a company that does not have comprehensive access to voter data and a person who has not been established as a credible source or expert on voting in any way. In other words, he’s corrected his position back to the standard Republican talking points of using unsubstantiated, shoddy, or willfully misinterpreted data to support claims of fraud, and thus an agenda of more restrictive voting laws that only discriminate in effect, not in intent. But in his story about Bavarian golfers and “Latin American” voters, Trump perhaps inadvertently ushered in a new era. One of the strongest unofficial powers of the office is to set and maintain norms, and if the leader of America is open in using racism to advance racially-disparate policy, his party at the least should feel emboldened.

Maybe Trump just isn’t a deft enough politician to grasp the importance of maintaining the cloak of colorblindness in his calls for voter integrity. But the deeper implication is that such a cloak may no longer matter. After winning an election steeped in some rather overt appeals to racism and hatred of immigrants, why should the new president feel inclined to blunt his language? Underlying all the bemoaning of political correctness in his rhetoric is the Rosetta Stone of Trumpism: that Trump wants to be able to say the thing again. And with that comes a whole new world of possibilities for voter suppression.