On Friday, one of the softer voices in the savage feud between City Hall and the police department explained in bare terms why Mayor Bill de Blasio" class="company-link">Bill de Blasio is not bridging the divide.

Mr. de Blasio does not even think there is a rift, Michael Palladino, the president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, complained.

“Based on my own life experiences, in order to address or fix a problem, you first have to acknowledge that problem exists and at this point, I’m not convinced the mayor acknowledges that,” Mr. Palladino told Geraldo Rivera on WABC.

A half century ago, the likes of Mr. Palladino were raging against—and lamenting—another tall liberal mayor who ran on a platform of overhauling the NYPD. Like in 2015, 1965 saw a collision between an aggressive, reform-minded executive and a police force with a burgeoning hatred for the new mayor who rode a progressive wave to power.

“It is very reminiscent of John Lindsay,” said George Arzt, a Democratic consultant who covered the Lindsay administration as a reporter for the New York Post.

To the people old enough to remember the at once ambitious, glamorous and exceedingly chaotic two terms of Mayor John Lindsay, the first year of Mr. de Blasio’s tenure is an eerie echo of that hopeful yet maddening era of the city’s history. Once more, police unions are in open revolt against a proud progressive who is trying to bring new reforms and oversight to the department. Once more, a black and Hispanic electorate is applauding a lanky white mayor with an Ivy League pedigree as a bloc of white, outer borough voters seethe.

Mr. de Blasio’s New York, of course, is not Lindsay’s. The city Lindsay governed from 1966 to 1973 grappled with skyrocketing crime, crippling labor strikes, white flight and the erosion of a manufacturing base that long powered the local economy. In a sense, the dynamics Mr. de Blasio confronts today are in a shrunken, more manageable form than the unrest Lindsay was forced to contend with in his wild eight years.

For all the talk of Mr. de Blasio losing control of New York and his police force, he enters his second year of his office in a far stronger position than Lindsay, a liberal Republican in a Democratic town, ever knew—though one of the last unabashed progressives, a true believer in a big, activist government that could remake society, to lead the city had plenty in common with Mr. de Blasio, who stands around an inch taller than Lindsay at about six-foot-five.

When Mr. de Blasio wants to reference the mayors of the past, he goes way back to Fiorello La Guardia, a hero of liberals everywhere, or David Dinkins, the gentlemanly Democrat Mr. de Blasio worked for in the early 1990s. Lindsay is never mentioned.

To anyone who lived through the Lindsay years or studied him, that’s not exactly a surprise.

“Lindsay was very controversial and so there’s a lot of associations he would rather avoid. Lindsay was a very polarizing figure,” said Joseph Viteritti, a professor at Hunter College and the editor of “Summer in the City: John Lindsay, New York, and the American Dream.” “There’s no great benefit for Bill de Blasio politically to identify with Lindsay.”

Case in point: a spokesman for Mr. de Blasio would not answer any questions about Lindsay, including whether Mr. de Blasio drew any lessons from his time in office. But one Lindsay confidante who knows Mr. de Blasio well said the mayor has studied the old New York that the Lindsay administration once dubbed “Fun City.”

“When I talk to de Blasio personally, and other people from the [Lindsay] administration speak to him, he’s made it a big point to talk about that history,” said Sid Davidoff, a lobbyist and a longtime administrative assistant to Lindsay. “He’s very interested in the history of the Lindsay administration. He has been quite clear in asking very pointed questions about what happened in that era.”

****

Lindsay, a strapping Yale-educated congressman from the Upper East Side, earned the enmity of the overwhelmingly white, Irish police unions when he called for civilian oversight of the NYPD in his first campaign speech in May of 1965. For the critics today that say Mr. de Blasio is the first mayor to enrage rank and file officers about something other than contracts, Lindsay’s political career offers a striking correction to that argument.

In a boiling decade when the civil rights movement was in full swing and police were clashing with African-Americans across the nation, Lindsay believed the NYPD needed a Civilian Complaint Review Board to serve as a check on their power and show the public, particularly minorities, that a white police force could be held accountable by unbiased people outside the department. The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, then led by John Cassese, vociferously opposed a CCRB. Mr. Davidoff recalled meeting cops that year and finding some with William F. Buckley Jr. pins inside their coats—demonstrating their outright support for the Conservative Party mayoral candidate and budding intellectual icon of the right.

“In those days, it’s a little hard to realize today, the CCRB was really a very narrow issue that largely came out of the civil rights movement. Lindsay was unusually early, particularly for a white political leader, to advocate for it,” recalled Jay Kriegel, a senior adviser at Related Companies and former special counsel to Lindsay.

“It generated enormously negative reactions from police. In the summer of 1965 at a City Council hearing, 5,000 cops showed up to protest at City Hall,” he added.

Lindsay, like Mr. de Blasio, courted voters of color and would go on to forge an unusually close bond with marginalized blacks and Puerto Ricans—in the 1960s, Puerto Ricans were the only significant Hispanic minority in New York City. Cassese fumed to the Daily News that Lindsay was “not acting as the mayor of all the people. He seems to be acting as the mayor of a portion of the populace … to the detriment of all the other people that live in this town.”

Cassese, like today’s PBA President Patrick Lynch, could be even more blunt: “I am sick and tired of giving in to minority groups, with their whims and their gripes and shouting. Any review board with civilians on it is detrimental to the operations of the police department,” he said.

The PBA hated Lindsay’s CCRB so much they forced a referendum on the board in 1966. It was soundly defeated in a popular vote, a major blow to the debonair progressive. Police would subsequently stage slowdowns much like the one Mr. de Blasio is confronting now and some cops even refused to go on patrol in the winter of 1970 and 1971. When Lindsay attended the funeral of a slain NYPD officer in 1972, he was booed.

Working class, outer borough whites, never warm to the patrician mayor who eagerly walked the streets of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant, grew to despise Lindsay. The depth of their rage may have been captured best in New York Magazine, where Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill, themselves the sons of the outer boroughs, wrote about how white New Yorkers were ready to revolt.

“The working-class white man,” Mr. Hamill wrote, “does not like John Lindsay, because he feels Lindsay is only concerned about the needs of blacks; he sees Lindsay walking the streets of the ghettos or opening a privately-financed housing project in East Harlem or delivering lectures about tolerance and brotherhood, and he wonders what it all means to him.”

On issues of race, Lindsay was often ahead of the curve for an elected official, but this spelled doom at a time when whites had far more political clout than blacks. With the help of a black New York City Housing Authority chair, Simeon Golar, Lindsay attempted to erect public housing in the white, middle class enclave of Forest Hills, Queens. Residents furiously battled the Lindsay administration and a young lawyer named Mario Cuomo was called in to mediate the dispute.

Opinion polls reveal a yawning racial divide in 2014 and 2015 quite similar to what Lindsay knew: minorities cheer Mr. de Blasio while whites, particularly those beyond the brownstone belt, desert the Democrat. In a December Quinnipiac University poll, only 32 percent of whites approved of Mr. de Blasio’s performance. 70 percent blacks gave him a thumbs up. Many pundits believe that gulf could widen.

“They really hate de Blasio out here,” one eastern Queens Democrat confessed. “They don’t feel like he does anything for them or cares about them. It’s really bad.”

Like in Lindsay’s era, Mr. de Blasio’s politics aren’t squaring with the slice of the electorate that didn’t power his stunning campaign victory in 2013. In neighborhoods like Bayside, Riverdale, Bay Ridge, Howard Beach and Tottenville, policies like building affordable housing, handing out municipal identification cards and knocking down the city speed limit five miles per hour are not palatable. For the homeowner with a car and a drivers license, rising property values aren’t so awful, a falling speed limit is an inconvenience and another I.D. card is just redundant.

To residents there, Mr. de Blasio is an imperious Park Slope liberal, pandering to the allegedly anti-police protesters who swamped bridges and highways after a white police officer was not indicted in the death of Eric Garner, a black man, last July. They don’t want to hear their mayor utter “black lives matter” or talk about the caution his biracial son must take when dealing with police.

They are nostalgic for Michael Bloomberg and Rudolph Giuliani. They grumble about the “bad old days” coming back, even with crime at record lows. They usually have a neighbor, a friend or a relative who is a disgruntled cop.

Errol Louis, the host of NY1’s Inside City Hall and a newspaper columnist, suggested in the Daily News that Mr. de Blasio do more to incorporate these people into his vision, even if they didn’t vote for him and don’t welcome his activist approach to government.

“The band of City Hall insiders needs to be greatly broadened, with more representation from the mostly white, working-class communities in the Rockaways, Staten Island, Bayside and other enclaves that feel neglected, ignored and shut out,” he wrote.

****

Police officers have literally turned their backs on Mr. de Blasio three times and NYPD union leaders blame him for creating an environment, through his public comments and actions, that led a mentally unstable man to murder two cops last month.

The union leaders want Mr. de Blasio to apologize. Mr. de Blasio and his allies don’t think they have anything to apologize for. “I respect the question but the construct is about the past and I just don’t want to do that. I think this is about moving forward,” Mr. de Blasio defiantly told reporters when asked about the possibility of an apology.

Lindsay’s own problems with the city’s labor leaders, which far outstripped the NYPD acrimony Mr. de Blasio can’t seem to escape, do illustrate another parallel between the two mayors: each had a difficult time relating to those who disagreed with them.

Lindsay, like Mr. de Blasio, was a deeply principled progressive reluctant to cede any ground to his opponents. His refusal to negotiate with Michael Quill, the irascible president of the Transport Workers Union, led to a devastating transit strike on the first day of his first term.

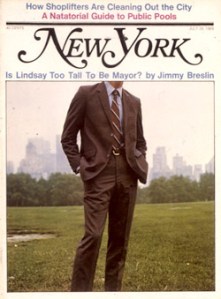

“He was talking down to old Mike Quill, and when Mike Quill looked up at John Lindsay he saw the Church of England. Within an hour, we had one hell of a transit strike,” Mr. Breslin wrote in a 1969 New York Magazine story titled “Is Lindsay Too Tall To Be Mayor?”

The two mayors flanked themselves with like-minded liberals. Lindsay’s early administration was youthful and reformist like he was; Mr. de Blasio, a staunch Democrat, made it clear last year only people who shared his values could work in City Hall.

“Mayor Bill de Blasio has a lot of advisers that think like he does,” said Joseph Lhota, a deputy mayor under Republican Rudolph Giuliani and Mr. de Blasio’s GOP opponent in 2013. “It’s very important to get a multitude of approaches so you’re not surprised when someone has a different point of view or when the public moves in a different direction.”

To critics, self-righteousness is another shared trait of both men. Mr. de Blasio, in the tone of a peeved parent, has lectured reporters repeatedly about how they cover news, whether it was the scandals that forced a top aide, Rachel Noerdlinger, to resign, or the mass protests roiling the city after the Garner grand jury decision. Lindsay, enraged at criticism by City Hall reporters, banned the press from the main-floor washroom, according to the New York Times.

****

The Dinkins administration resurrected Lindsay’s CCRB decades later and it still stands today, joining the new NYPD inspector general as another form of oversight that the police unions resent but must accept. The NYPD may not be much more content than it was under Lindsay–or Dinkins or Giuliani, for that matter–but the city and its racial composition has changed drastically in 50 years.

The white electorate, so united in their anger against Lindsay, has shrunk, and New York is a now a minority majority city. These minorities vote.

Rising rents threatens the ability of the working class to live here, but the economy is still strong and the city’s population continues to grow. For all the unrest that came after the grand jury decisions in Ferguson, Mo. and Staten Island, the intensity of this decade pales in comparison to Lindsay’s 1960s, when cities, ever plagued with race riots and gun violence, could be volatile and frightening places to live.

After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, Lindsay drove up to 116th Street in Harlem to tell people how sick and sorry he was that King had died. It seemed to work, and New York avoided the cataclysmic riots that consumed cities like Newark and Los Angeles.

A year later, Lindsay struggled mightily to win re-election, losing the Republican primary to John Marchi, a Staten Island state senator who made it his life’s work to break his home borough away from the rest of the city. Lindsay eked out a victory on the Liberal Party line, besting Marchi and the conservative Bronx Democrat Mario Procaccino.

His apologized for mistakes of his first term, like mishandling the clean-up of a snowstorm, and branded the New York City mayor the second toughest job in America. With the city’s fiscal situation deteriorating and his popularity fading in the early 1970s, he briefly ran for president as a Democrat and decided against seeking a third term. He died in 2000.

As Mr. Viteritti, the editor of “Summer in the City,” pointed out, Lindsay was always in the precarious position of drawing power from a nonwhite bloc that only constituted about a third of the city. The calls for law and order from a white majority outweighed the racial injustices Lindsay hoped to cure. The NYPD, unlike today, was systemically corrupt and far more trigger-happy.

“Even with this fight with Bill de Blasio and the police department, with all the rhetoric going back and forth, popular opinion is much more reasonable today,” Mr. Viteritti said. “They understand the dilemmas of police and there’s also a greater understanding that the department has to reconsider the way it does business. The public is much more reasonable than it was in the days of John Lindsay.”