If Peter McNeish had done nothing more than organise the Sex Pistols’ June 1976 gig at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall with his college friend Howard Trafford, then he could still reasonably have claimed to have made a vast impact on the face of rock music. Hastily arranged by two students who had no idea what they were doing, and sparsely attended (“I think there were about 42, 43 people there,” McNeish later recalled, “and I’m not sure whether that’s counting me and Howard or even the Sex Pistols”), it is nevertheless among the most influential gigs in British pop history. The question of who precisely was there is so vexed that an entire book has been devoted to tracking audience members down, but among those who did turn up were future members of Joy Division, the Fall and the Smiths, as well as Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, all of whom seem to have been immediately galvanised by the performance. “A friend who was with me said, ‘Jesus, you could play guitar as good as that,’” recalled Bernard Sumner. “We formed a band that night,” said Peter Hook.

So did McNeish and Trafford: by the time the Sex Pistols returned to Manchester six weeks later, they had changed their names – Trafford became Howard Devoto, McNeish Pete Shelley, tellingly the name his parents would have given him had he been born a girl – recruited a bass player and drummer, and were acting as the Pistols’ support act under the name Buzzcocks. By the end of 1976, they had recorded their first release, the Spiral Scratch EP. It remains the essential document of punk rock hitting the provinces, of the Sex Pistols’ big idea being twisted into something else by people outside of London.

Packed with smart, witty, sardonic ideas – not least Shelley’s two-note guitar solo on Boredom, both a screw-you to accepted mid-70s notions of musicianship and evidence of his love of Krautrock’s minimalism – its four songs hurtle by breathlessly, nearly stumbling over themselves, as if the band are consumed by urgency, a belief that their window of opportunity is about to pass. It was recorded live, its cover was a Polaroid photo and the band and manager, Richard Boon, released it themselves. It wasn’t the first independently released record in British rock history, but because it appeared when it did, it became the most influential. Its release inspired a wave of punk and post-punk independent labels, and, by default, an entire genre: what we now call “indie” music begins with Spiral Scratch.

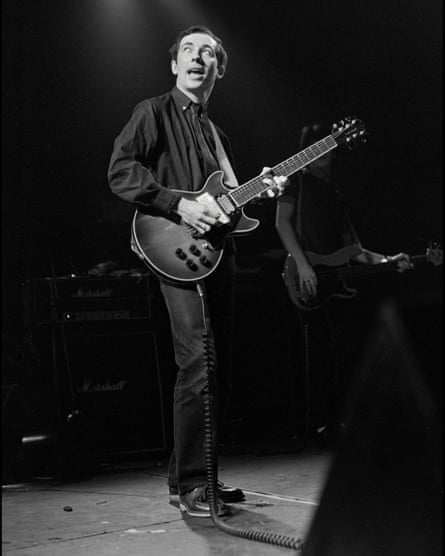

Buzzcocks’ story should have ended there: in a very punk move, frontman and lyricist Devoto almost immediately quit the band, declaring punk “old hat”. Instead, Shelley became their lead singer, which changed the way Buzzcocks sounded entirely. Devoto’s voice had been a nasal post-Johnny Rotten sneer, but Shelley sang in an arch, camp north-western accent that seemed to drawl even when the music behind it rattled along at breakneck pace, and proved perfect for delivering withering put-downs when punk crowds became too tumultuous. “Oh my God,” he sighs as a Leeds audience erupt into violence on the live bootleg Razor Cuts, “you’re so bloody boring.”

At first, the band continued ploughing through the songs they had written while Devoto was on board, including their next single, Orgasm Addict, a gleefully vicious portrayal of a compulsive masturbator. But gradually, Shelley’s solo material came to the fore. Despite a pre-punk background in experimental music – some Throbbing Gristle-ish electronic recordings he’d made in 1974 were released in the early 80s as an album called Sky Yen – he specialised in compact, perfectly constructed pop songs. And his specialist subject was love, almost invariably unrequited. Perhaps understandably, given the atmosphere of violence and machismo that quickly surrounded the punk scene, Shelley never came out as gay or bisexual, but something about his songs – always genderless, so his audience had no idea whether the subject was a man or a woman – and the way he sang them, let the sharper listener know about his sexuality. Behind I Don’t Mind, What Do I Get? or Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) lurked the distinct implication that he’d been spurned because the object of his affections was a straight man: “I always wanted something I never could get,” he protested on Everybody’s Happy Nowadays.

Complex but immediate, packed with melodic hooks and waspishly funny lines, they were the kind of songs that artists spend their whole careers striving towards. Shelley just wrote one after the other as if it was the easiest thing in the world: Love You More, Promises, Fiction Romance, Sixteen Again, Get on Our Own, Nostalgia. In the process, he piloted Buzzcocks through perhaps the greatest run of singles of any punk band: by mid-1978, they were such a regular fixture on Top of the Pops that their sound could be the subject of a hit parody, Jilted John’s Jilted John. Indeed, his pop songs were so good that they tended to overshadow Buzzcocks’ more experimental side, where Shelley’s love of Can was given free rein: the tense repetitions of ESP, the juddering instrumental Late for the Train and, especially, Moving Away from the Pulsebeat, the thunderous closer of their 1978 debut album, Another Music in a Different Kitchen.

This experimentation was more to the fore on their third album, 1979’s A Different Kind of Tension – on Hollow Inside, he pared his writing down to two cyclical lines – but the album was only patchily brilliant and, by then, Buzzcocks’ star was fading: incredibly, what may be Shelley’s greatest pop single, You Say You Don’t Love Me, failed to make the charts at all. It was probably a mistake to invite Joy Division to be support act on the subsequent tour: things moved fast in the post-punk world, and their sparse sound and the unprecedented sight of Ian Curtis in full flight had the unfortunate side effect of making Buzzcocks look, as their erstwhile frontman would have put it, old hat. They soldiered on for three more ignored and underrated singles, contributed one final flash of concise pop brilliance, I Look Alone, to a compilation released by Rough Trade, one of the labels they had inspired into existence, then split up.

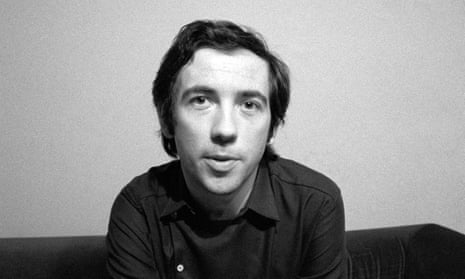

Shelley’s post-Buzzcocks career was frustrating. He made two strong solo albums that fitted with the contemporary vogue for electronic pop. The brilliant title track of the first, Homosapien, should have been a huge hit, but this time he went too far in tipping the wink to listeners and the song was banned by the BBC for “explicit reference to gay sex”. Today, its suggestion that gender and sexuality are fluid, malleable things – “I don’t want to classify you like an animal in the zoo” – seems less shocking than remarkably prescient. Heaven and the Sea, from 1986, showed his pop smarts were still intact, but he wasn’t suited to making a glossily produced mid-80s rock album.

Ironically, it arrived just as Buzzcocks’ 70s records had become hugely influential. In 1986, as “indie music” ceased being a reference to a means of distribution and became a description of an identifiable sound, you couldn’t move for bands trying to emulate their distorted guitars, Shelley’s terse songwriting style and air of perpetual romantic despair. Rather than capitalise on it, Shelley formed Zip, a band who attempted to meld drum machines and electronics with punky guitars: they only released one single – Your Love, a far better record than its muted reception suggested – before he conceded to the inevitable and reformed Buzzcocks in 1989.

Initially just a touring concern, they resumed recording in 1993, with the album Trade Test Transmissions more or less picking up where they had left off. Their subsequent albums were far better than a reformed punk band doing the rounds in middle age had any right to be: 1996’s All Set co-opted Green Day producer Neill King, a sly acknowledgement of the band’s other vast influence on modern rock – they had effectively minted the pop-punk sound that made Green Day and Rancid millions. A project called Buzzkunst, in 2002, saw Shelley and Devoto reunited for an intriguing, angular electronic album, but the following year’s Buzzcocks came closest to matching their earlier glory, offering a noticeably darker, more mature take on their trademark sound.

Live, however, Buzzcocks always relied on their 70s catalogue. Pete Shelley had written songs that did the one thing no one at the time thought punk would do: they lasted, slipping their overtones of spittle-flecked confrontation to become universal, a beloved part of the musical landscape. These days, you’re never that far away from a DJ playing Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve) on BBC Radio 2, a notion that would have seemed hysterical when it was written. As it turned out, the moment that seemed so fleeting in 1976 that Buzzcocks needed to document it before it vanished – “your time’s up”, as one chorus on Spiral Scratch predicted – was anything but.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion