Death in the clouds: The problem with Everest’s 200+ bodies

iStock

iStockThey lie frozen in time, thousands of metres above sea level. The grim death toll on Everest is becoming impossible to ignore, says Rachel Nuwer.

“But when I say our sport is a hazardous one, I do not mean that when we climb mountains there is a large chance that we shall be killed, but that we are surrounded by dangers which will kill us if we let them.”

- George Mallory, 1924

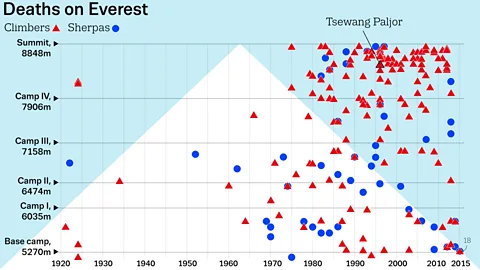

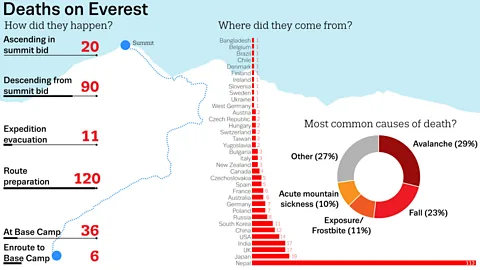

No one knows exactly how many bodies remain on Mount Everest today, but there are certainly more than 200. Climbers and Sherpas lie tucked into crevasses, buried under avalanche snow and exposed on catchment basin slopes – their limbs sun-bleached and distorted. Most are concealed from view, but some are familiar fixtures on the route to Everest’s summit.

Perhaps most well-known of all are the remains of Tsewang Paljor, a young Indian climber who lost his life in the infamous 1996 blizzard. For nearly 20 years, Paljor’s body – popularly known as Green Boots, for the neon footwear he was wearing when he died – has rested near the summit of Everest’s north side. When snow cover is light, climbers have had to step over Paljor’s extended legs on their way to and from the peak.

(Read part one of this story, exploring who Paljor was and how he got there).

Mountaineers largely view such matters as tragic but unavoidable. For the rest of us, however, the idea that a corpse could remain in plain sight for nearly 20 years can seem mind-boggling. Will bodies like Paljor’s remain in their place forever, or can something be done? And will we ever decide that Mount Everest simply is not worth it? As I discovered in this two-part series, the answer is a story of control, danger, grief and surprises.

Nigel Hawtin

Nigel HawtinBefore answering those questions, however, it is worth asking something more fundamental: when death is all around, why do people gamble their lives on Everest at all?

Reaching the highest point on Earth once served as a symbol of “man’s desire to conquer the Universe,” as British mountaineer George Mallory put it. When a reporter once asked him why he wished to climb Everest’s 8,848m (29,029ft)-high peak, Mallory snapped “Because it’s there!”

Everest, however, is no longer the romantic, unconquered place it once was. Since Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary became the first men to stand on its summit in 1953, the mountain has been summited more than 7,000 times by more than 4,000 people, who have left a trail of garbage, human waste and bodies in their wake.

Rex

Rex“Climbing Everest looks like a big joke today,” says Captain MS Kohli, a mountaineer who in 1965 led India’s first successful expedition to summit Mount Everest. “It absolutely does not resemble the old days when there were adventures, challenges and exploration. It’s just physically going up with the help of others.”

For Sherpas and others hired to work on Everest, the reason they keep coming back is that it’s a high-paying job. For everyone else, however, motivations are often difficult to explain, even to oneself. Professional climbers often insist that their drive differs from that of the majority of clients who pay to climb Everest, a group that is frequently accused of the lowliest of motivations: bagging the world’s highest mountain for bragging rights. “Somebody once said that climbing Everest is a challenge, but the bigger challenge would be to climb it and not tell anybody,” says Billi Bierling, a Kathmandu-based journalist and climber and personal assistant for Elizabeth Hawley, a former journalist, now 91, who has been chronicling Himalayan expeditions since the 1960s.

But few would actually admit that they climb Everest only so they can boast about it later. Instead, Everest tends to assume a symbolic importance for those who set their sights on it, often articulated terms of transformation, triumph over personal obstacles or the crown jewel in a bucket list of lifelong goals. “Everyone has a different motivation,” Bierling says. “Someone wants to spread the ashes of their dead husband, another does it for their mother, others want to kill a personal demon.”

“In some cases, it’s just ego,” Hawley adds. “In fact you have to have a certain amount of ego to get up the damn thing.”

As for professional climbers, whose love of mountaineering extends well beyond Everest, psychologists have tried to weed their motivations out for decades. Some concluded that high-risk athletes – mountaineers included – are sensation-seekers who thrive off thrill. Yet think for a moment about what climbing a mountain like Everest entails – weeks spent at various camps, allowing the body to adapt to altitude; inching up the mountain, step-by-step; using sheer willpower to push through unrelenting discomfort and exhaustion – and this explanation makes less sense. High altitude climbing, in fact, is a slog. As Matthew Barlow, a postdoctoral researcher in sports psychology at Bangor University, Wales, puts it: “Climbing something like Everest is boring, toilsome and about as far from an adrenaline rush as you can get.”

A climber himself, Barlow suspected that sensation-seeking theory has long been misapplied to mountaineers. His research suggests that, compared to other athletes, mountaineers tend to possess an exaggerated “expectancy of agency”. In other words, they crave a feeling of control over their lives. Because the complexities of modern life defy such control, they are forced to seek agency elsewhere. As Barlow explains: “To demonstrate that I have influence over my life, I might go into an environment that is incredibly difficult to control – like the high mountains.”

Flirting with mortality, in other words, is part of the appeal. “If you can escape death or dodge fatal accidents, it allows you the illusion of heroism, even though I don’t think it’s truly heroic,” says David Roberts, a mountaineer, journalist and author based in Massachusetts. “It’s not like playing poker where the worst that could happen is you lose some money. The stakes are ultimate ones.”

Rex

RexBarlow and colleagues also found that mountaineers believe that they struggle emotionally, especially when it came to loving partner relationships. They may compensate for this by becoming experts at dealing with emotions in another, more straightforwardly terrifying realm. “The emotional anxiety of everyday life is confusing, ambiguous and diffuse, and you don’t know the source of it,” Barlow says. “In the mountains, the emotion is fear, and the source is clear: if I fall, I die.”

In her decades interviewing mountaineers, Hawley, too, has noticed this tendency. “In some cases, climbers just want to get away from home and responsibilities,” she says. “Let the mother take care of the son that’s sick, or deal with little Johnny who got in trouble at school.”

Many of the climbers Barlow and his colleagues included in their study – especially professional ones – also exhibited what psychologists refer to as counterphobia. Rather than avoid the things they fear, they feel compelled to face-off with those elements. “It’s a misnomer that climbers are fearless,” Barlow says. “Instead, as a climber, I know I will be afraid, but the key bit is that I approach that fear and try to overcome it.”

Like a junkie who’s got his fix, mountaineers usually report a transfer effect from their experience – a feeling of satiation immediately after returning from a peak. “For me, coming back from a climb physically exhausted but mentally relaxed is the dream,” says Mark Jenkins, a journalist, author and adventurer in Wyoming.

To continue to sate that desire, mountaineers thus set their sights on increasingly challenging peaks, routes or circumstances, and as the world’s highest mountain, Everest has a natural place in that progression. “You have to up the ante, which over time leads to greater and greater risk taking,” Barlow says. “If the transfer effect is never enough for you to stop, then ultimately you likely die.”

Given all this, climbers must decide for themselves if their passion is worth potentially losing their lives – and abandoning their loved ones – for. “On my own volition, I accept the risk and suffering, and that there is no external benefit to society,” says Conrad Anker, a mountaineer, author and leader of the North Face climbing team. “But as long as one is clear and transparent with your family and wife, then I don’t think it’s morally incorrect.”

Some, however, do get their fill. Seaborn Beck Weathers, a pathologist in Dallas who lost his nose and parts of his hands and feet – and very nearly his life – on Everest in 1996, was originally attracted to climbing precisely because of a paralysing fear of heights. As he described in his book, Left for Dead, facing off in the mountains with that fear proved to be an effective (albeit temporary) antidote for his severe depression. Everest was his last mountaineering experience, though, and that close call with death saved his marriage by causing him to realise what was truly important in life. Because of that, he does not regret it. But at the same time, he would not recommend anyone to climb Everest.

“My view has changed on this fairly dramatically,” he says. “If you don’t have anyone who cares about you or is dependent on you, if you have no friends or colleagues, and if you’re willing to put a single round in the chamber of a revolver and put it in your mouth and pull the trigger, then yeah, it’s a pretty good idea to climb Everest.”

Nigel Hawtin

Nigel HawtinWar zones aside, the high mountains are the only places on Earth where it is expected and even normal to encounter exposed human remains. And of all the mountains where climbers have lost their lives, Everest likely carries the highest risk of coming across bodies simply because there are so many. “You’ll be walking along, it’s a beautiful day, and all of a sudden there’s someone there,” says mountaineer Ed Viesturs. “It’s like, wow – it’s a wakeup call.”

At times, the encounter is personal. Ang Dorjee Chhuldim Sherpa, a mountaineering guide at Adventure Consultants who has summited Everest 17 times, was good friends with Scott Fischer, a mountain guide who died in the 1996 disaster on Everest’s south side. After his death, Fischer’s body remained in sight. “When you’re passing by and you see your friend lying there, you know exactly who it is,” he says. “I try not to look, but my eyes always go there.”

“People are somehow able to walk by these bodies and continue climbing by rationalising to themselves that whatever happened to this person will not happen to me,” says Christopher Kayes, chair and professor of management at the George Washington University in Washington DC.

Some, however, are not able to continue climbing. In 2010, Geert van Hurck, an amateur climber from Belgium, was making his way up Everest’s north side when he came across a “coloured mass” on the ground. Realising it was a climber, Van Hurck quickly approached, eager to offer any help he could. That was when he saw the bag. Someone had placed a plastic bag over the man’s face to prevent birds from pecking out his eyes. “It just didn’t feel right to climb any further and celebrate at the summit,” Van Hurck says. “I think maybe I was seeing myself lying there.” He would almost certainly have summited, but returned to camp, shaken and upset.

Rex

RexHis decision to turn back, however, is rare. Hundreds of climbers have passed corpses en-route to their summit, often without knowing who they are. Indeed, almost immediately after Paljor died, uncertainty has surrounded his remains. Some even doubt that the body belongs to Paljor at all, thinking it more likely to be his climbing partner, Dorje Morup. But for whatever reason, Paljor’s identity has largely stuck, even if most climbers today know the remains only as Green Boots, and the place where he rests as Green Boots’ Cave.

That enclave, located at about 8,500m high and sheltered from the wind, is a popular resting point for climbers on their way back from the summit, who may sit down there to catch their breath or have a snack. “It’s pretty grisly that they named that cave after him,” says amateur mountaineer Bill Burke, the only person to have climbed the highest mountain on every continent after age 60. “It’s really become a landmark on the north side.”

In 2006, the cave – and Green Boots – earned even more infamous renown when a British climber named David Sharp was discovered huddled inside, on the brink of death. The story was widely circulated by the media, which claimed that some 40 climbers passed Sharp by, who died later that day, without offering aid. As is so often the case, however, much of the story’s nuance was lost in those reports; in fact, most climbers did not notice Sharp, or assumed that he was simply resting. Others accused of ignoring his plight were not informed until it was much too late to help.

Sharp’s body was removed from sight a year later at the request of his parents, but Paljor, whose moniker was further solidified by the incident, remained.

Rex

RexWhat to do with bodies on the mountain depends on a number of factors, including the wishes of the deceased and his or her families, and where the death took place. Some make arrangements for their body to be returned to their family, if possible. Burke did not discuss those details with his wife, but he did ensure that his body would be delivered to her, should the worst happen. “It’s not something you dwell on,” he says. “I knew I needed repatriation insurance so I got it, but I didn’t give it a lot of thought.”

Returning a body to a family costs thousands of dollars, however, and requires the efforts of six to eight Sherpas – potentially putting those men’s lives in danger. “Even picking up a candy wrapper high up on the mountain is a lot of effort, because it’s totally frozen and you have to dig around it,” says Ang Tshering Sherpa, chairman and founder of Asian Trekking, a company based in Kathmandu, and president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association. “A dead body that normally weighs 80kg might weigh 150kg when frozen and dug out with the surrounding ice attached.”

Typically, though, mountaineers who die on a mountain wish to remain there, a tradition co-opted from seafarers more than a century ago. “But when we have 500 people stepping over a body ever year, that’s no longer acceptable,” says Jenkins, who had to navigate four bodies when he was last on Everest. “That’s disgraceful.”

When a body does become a well-photographed fixture of the mountain, families are often the ones who suffer most. “One day you’re waving goodbye at the airport, and the next is, ‘Oh, dad’s called Green Boots and they’re walking past him,’” says Greg Child, a mountaineer and author in Utah.

Paljor’s brother Thinley recalls the moment he discovered the nickname, along with photos, in 2011: “I was on the internet, and I found that they’re calling him Green Boots or something,” he says. “I was really upset and shocked, and I really didn’t want my family to know about this.”

“Honestly speaking, it’s really difficult for me to even look at the pictures on the internet,” he says. “I feel so helpless.”

Funeral rights

To avoid this, remains are usually “committed” to the mountain – that is, they are respectfully pushed into a crevasse or off a steep slope, out of sight. When possible, they might also be covered with rocks, forming a burial mound. But Dave Hahn, a mountain guide at RMI Expeditions who has reached Everest’s summit 15 times, emphasises “the time to move a body is when the accident happens.” Afterwards, “not to get grotesque, but they become attached to the hill.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut even for a fresh body, those respectful acts can take hours and require the effort of several fit climbers. The question remains of whose responsibility that task should fall to, especially as more bodies have built up over the years, and glacial melting due to climate change has caused others to appear.

Some have stepped up. Since 2008, Dawa Steven Sherpa, managing director of Asian Trekking and Ang Tshering’s son, and his colleagues have led yearly clean-up efforts on the mountain, removing more than 15,000kg of old garbage and more than 800kg of human waste. As such, whenever a body or body parts emerge from the melting, ever-dynamic Khumbu glacier, his team is seen as the de facto removal crew. So far, they have respectfully disposed of several bodies, four Sherpas – one of whom they knew – and one Australian climber who had disappeared in 1975. “If at all possible, human remains should get a burial,” Dawa Steven says. “That’s not always possible if a body is frozen into the slope at 8,000m, but we can at least cover it and give it some dignity so people don’t take pictures.”

A mother’s end

One particular story of a body’s recovery illustrates both the human cost, and the lengths that it can take to show the dead the proper respect.

Francys Distefano-Arsentiev died on Everest in 1998, and came to be known as “Sleeping Beauty”. Her son, Paul Distefano recalls just how distressing it was seeing photographs of his mother’s body online. “It’s like being really embarrassed, like being called on by your teacher but not knowing how to read. It’s horrible.”

Rex

RexWhen he was 11, Paul’s mother, a world-class climber, had set her sights on becoming the first American woman to climb Everest without bottled oxygen. “I don’t know why she decided she had to do it without oxygen, but I think she felt like she needed to prove something,” Paul says. “I think she also felt invincible because she was with Sergei, my stepdad. His nickname was ‘the snow leopard’ because he was so agile.”

The day before Francys left, she dropped by Paul’s school in Telluride, Colorado, and told him, “I’m going to leave this up to you.” In one of the most vivid memories he has, he remembers telling her, “If I tell you you can’t go, then at some point you’ll be an old lady in a rocking chair saying, ‘Dang, I should have done that.’ I don’t want to be the one to take that from you.”

That night, however, Paul had a nightmare: two mountaineers, a complete whiteout, snow surrounding them like attacking bees. When he woke up, he phoned his mother, telling her that he had changed his mind. “You know Paul,” she replied, “we talked yesterday, and you’re right: I have to do this.”

“I don’t think science can really explain why people want to climb these mountains,” he says. “In the end, the whole reason my mother climbed was because she had to.”

On May 22, 1998, Francys reached her goal and made Everest history. But on her descent from the peak, something went wrong. She and Sergei were forced to spend the night in the death zone and became separated. The following morning, Sergei suffered a fatal fall while attempting to rescue Francys, who had collapsed at around 8,850m (29,000ft). Climbers Ian Woodall and Cathy O’Dowd came across Francys at 05:00 and gave up their summit bid, staying with her for over an hour in subzero temperatures before they were forced to descend to ensure their own safety. Sometime later that morning, Francys succumbed to frostbite and exhaustion.

When Paul’s dad sat him down on a sunny afternoon and delivered the news, Paul felt like he had been hit with a sledgehammer. Yet he was hardly surprised. “To be honest, I already knew,” he says. “When someone that close to you dies, it’s strange and unexplainable, but you just know.”

Today, Paul harbors no resentment toward his mother. “I love her and wish she could be a part of my life, but she’s not,” he says. “Her death is certainly something I’ll always be dealing with, although in some ways it’s a blessing that my mom died doing what she loved.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYears passed, and Francys remained on the mountain. But Woodall, who had stayed with her in her dying hours, had become haunted by his inability to save her and deeply bothered by the fact that her body had become a landmark.

In 2007, Woodall, with O’Dowd’s support, returned to Everest specifically to remove Francys’ body from sight. “It was an opportunity to say goodbye,” he says. “But most importantly, to get her out of sight.”

After one false start, Woodall and Phuri Sherpa, who usually works on Everest but who volunteered to help, hiked up to the spot where he remembered leaving Francys – a steep slope, set at about a 60-degree angle and covered by broken shale. The original plan was to create a rock cairn for her, but to Woodall’s dismay, he found the area buried in four feet of snow. “There was no sign of her at all, just a huge, unstable snow slope,” he says.

The two began to dig. Thanks to a mix of luck and memory, they found Francys on the second try. A rock grave was no longer an option, but they had just enough rope to lower her body over the mountain’s edge. After wrapping her stiff remains in an American flag and saying a few words, they sent her on her way – likely to the same place where Sergei lies. All told, it took them five hours. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, much harder than going to the summit,” Woodall says. “But I felt strongly enough about it to get off my backside and do something about it.”

Paul, however, only learned of this development through the media, and at first felt some resentment for not being informed. “I was like, ‘Dude, that’s my mom!’” Eventually, though, he realised that Woodall and O’Dowd, having witnessed the final moments of his mother’s life, had forged their own special connection with Francys. “My mother and I are bonded by blood, and Ian, Cathy and her are bonded by death,” he says. “I feel that they had just as much a right to move her as we did, and my family honours their effort.”

“I wish they had asked me, I do, but more so I wish to make a connection with them and meet them,” he continues. “Hopefully that time will come.”

Rachel Nuwer

Rachel NuwerAfter reading about Woodall’s efforts to remove Francys’ body, Thinley contacted him about the possibility of doing the same for his brother Paljor. “What I find a bit odd is that Paljor was with a large Border Police team in ’96 but then they just packed up and went home and left him there,” Woodall says. “What’s more is, subsequently, the Indian Border Police has done other Everest expeditions and have gotten to the summit, but still left him there.”

The ITBP, however, says that Paljor’s body is hopelessly stuck, and that anyway, they can’t guarantee that it actually belongs to Paljor – or even to an Indian for that matter. “Some say it’s an ITBP body, some say it’s Indian and some say it’s a foreigner’s body,” says Deepak Pandey, an ITBP public relations officer in Delhi. “Our team saw it but we were not able to confirm if it’s our body or not.”

Accepting that he would get no help from the ITBP, Thinley offered to pay for Woodall’s mission to move Paljor, but had underestimated how much such a trip costs – in the $70,000 range. Woodall, meanwhile, had depleted his own funds in his effort to move Francys. “If I had the opportunity to go back, Paljor would be my number one priority,” he says. “But I really can’t afford to do it again on my own.”

“I just pray that my mom will never know about the Green Boots thing,” Thinley says. “She would be very, very, very upset. I can’t even imagine.”

Thinley had all but given up hope on putting his brother’s remains to rest. But last year, without warning, Paljor vanished.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAdventurer Noel Hanna made this discovery in May 2014, when he was surprised to find not only that Green Boots’ cave was devoid of its familiar resident, but also that many of the bodies on the north side – one stretch of which is sometimes referred to as “rainbow ridge,” for the colourful down suits of its many fallen climbers – seemed to have vanished. Hanna estimates that, previously, up to 10 bodies were visible on the push to the summit, but in 2014 he only counted two or three. “I would be 95% certain that [Paljor] has been moved or covered with stones,” Hanna says.

In keeping with Everest tradition, however, the circumstances surrounding the removal of the remains are not entirely clear. Hanna suspects that it could have been the Chinese Tibetan Mountaineering Association and the Chinese Mountaineering Association, which manage Everest’s north side. Five weeks prior to undertaking his climb, he had suggested to officials at a dinner that they move the bodies. “Apparently nobody had pointed that out to the person in charge before,” he says.

I asked Li Guowei, the deputy director of the foreign exchange department at the Chinese Mountaineering Association, for more details. He said that he was eager to provide answers to questions about the efforts, but that any media communications must be conducted through official channels. After more than a month of trying, however, he conceded that he did not think the request would receive approval from officials in Tibet any time in the near future.

“Their approach is very Chinese,” says Dawa Steven, who regularly works with them. “They don’t tell us what they’re doing and they don’t want the publicity.” The Chinese also do not like private teams to conduct their own clean-ups, he says. “From my perspective, it seems like it’s a matter of national pride.”

Relatives, however, do not seem to have been informed, as this news came as a surprise to Thinley. When I told him what I had heard, he paused for moment. “That’s a relief,” he finally said. “Thank you for telling me.”

Return to the mountain

Amid all the death, the pollution, the overcrowding and the increasingly questionable merit of reaching the summit, will people ever decide the mountain simply is not worth it anymore?

Not likely, if the past is anything to go on.

Just as the 1996 tragedy did nothing to quell people’s interest in Everest, the back-to-back horrors of the past two years seem to have had little effect. After the 2014 avalanche, many Sherpas vowed not to return to Everest until working conditions – including life insurance policies – were improved. For most, either out of economic necessity or choice, the sentiment to stay away from the mountain seems to have been short lived.

Ang Dorjee, for example, opted out of the 2015 season after losing three lifelong friends in the avalanche, but he now plans to return in 2016. “I was a bit scared, so I skipped the season,” he says. “But time passes, and I’ve been doing this all my life.”

“Nobody’s ok with what happened,” adds Dawa Steven. “The last few years have been very traumatising for a lot of the Sherpas.” But of the 63 Sherpas he has on payroll, none have tendered their resignation. “No one has said ‘I don’t want to climb anymore,’ although some have gotten pressure from their wives and parents to stop,” he says.

The same dynamic is playing out among Western guiding companies and leaders. Hahn has always defended Everest, but is now considering a break from the mountain. “I used to see the media stories that came out and they’d be only about death and destruction, and I’d say, ‘Well, my mountain is not about death,’” he says. “But the last two years have brought such a huge loss of life that it’s become hard for me to continue to make that argument.”

Yet Everest has a way of drawing people back in. Seven years ago, Mountain Madness, a company based in Seattle, suspended its guided climbs on Everest for an indefinite period of time, citing overcrowding and a surplus of inexperienced mountaineers. “We were trying to decide if we wanted to take a stance and say, ‘Hey, look, we just don't support what’s happening on Everest,’” says Mark Gunlogson, the company’s president. Next year, however, Mountain Madness plans to return. “It’s more due to client demand as opposed to us trying to get back into the game,” Gunlogson says.

“Everest hasn’t lost its mystique for me, or for many others who go back year after year,” Burke says. “Even having been there six times, I love climbing that mountain. I love going there. I’m almost addicted to it.”

For years to come – perhaps forever – Everest will no doubt continue to do what it has for decades: capture the imagination, provide the backdrop for dreams and personal triumphs, and take a few lives in the process. Green Boots may at last be at rest, but there is no guarantee that his cave will remain empty for long.

Read part one of this story, exploring who Paljor was and how he got there.

David Breashears/GlacierWorks

David Breashears/GlacierWorksProduced by filmmaker and campaigner David Breashears, for GlacierWorks (external site).