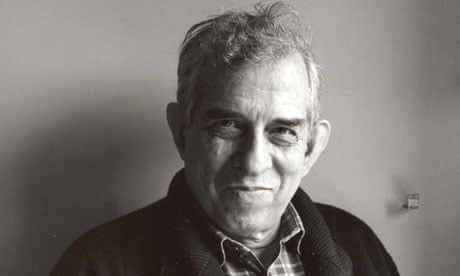

Aldo Clementi, who has died aged 85, was the last survivor of the great generation of Italian postwar musical avant-gardists. He was also its quietest and most self-effacing member, both personally and musically. After a hesitant start, he developed a technique that allowed him to produce works as calmly consistent in sound and technique as a Renaissance motet, and some would say just as beautiful.

He was born in Catania, Sicily, far from the centres of musical modernism. His talent was encouraged by his father, a keen amateur violinist. Aldo was a promising pianist, and in the salons of Catania he played the music that would one day be at the centre of his own, but mysteriously transformed: Bach, Schubert, Schumann and Mendelssohn. He also began to compose, receiving guidance from Alfredo Sangiorgi, a pupil of Arnold Schoenberg.

Clementi studied composition with Goffredo Petrassi, the great and still underrated master of Italian neo-classicism, at the Rome Conservatoire (1952-54), but emerged still unsure of his creative direction. The technical mastery and poised coolness of Petrassi and Stravinsky attracted him, but he was keenly aware that it was too caught up in the past for his present purposes.

By this time he had encountered the abstract painting of the Italian postwar school, and spent hours in the studios of Achille Perilli and others. He was inspired by the way their concepts and procedures yielded the "material" of the work, in a perfect closed loop, and imagined a music that would be similarly self-generating. This idea of a work that simply embodied the process that produced it was very much in the air at that time. In the 1960s it resurfaced in the US, in the early minimalist works of Steve Reich.

Attending the now-famous summer schools for new music at Darmstadt, in Germany, from 1955 onwards, helped Clementi out of his impasse. He hung back from embracing the hard-nosed serial procedures of Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, or the fierce leftwing polemics of Luigi Nono. Instead, he worked out a way of creating very dense, sustained sound aggregates, made out of a slowly circling tangle of mutually imitating contrapuntal lines. Each one is like a cut from a process that could continue circling indefinitely, presenting different facets to the listener as it rotates, in a way that Clementi compared to the mobiles of Alexander Calder.

The lack of highs and lows or any sense of forward movement reflected Clementi's distaste for rhetoric. He once declared, "Exaltation and depression have had their day: however you disguise them, they are modest symbols of a dialectic that is already extinct." Given that situation, the only thing left for music was to "assume the humble task of describing its own end, or at any rate its gradual extinction."

Silence would seem to be the inevitable end-point of such an attitude. In fact, Clementi's output became prolific from the 1970s onwards, and his music's quietism, far from being nihilistic, expresses a muffled joy. Philip Larkin's line about the particular beauty of trees in bud – "like something almost being said" – is very apt. To reach that state required a further epiphany, which came by chance in 1970. Clementi was asked to write a piece - B.A.C.H. for piano – using the name of JS Bach "translated" into musical notes. Clementi went further, embodying other material of Bach in a dense canonic weave, consuming and mysteriously transfiguring the originals.

Over the next three decades, Clementi infused this tender "pathos of distance" into all kinds of borrowed music, much of it taken from the classical repertoire that first claimed his affections as a child in Sicily (but not all – his Blues of 2001 for piano is based on a fragment of Thelonious Monk). The variety is enormous, ranging from delicate instrumental miniatures to a series of concertos for soloist, instrumental groups and toy carillons. All of them reveal Clementi's delight in creating a very exact sonorous world for each work, often bright and magical, sometimes tenebrous, as in Clessidra 2 (1996) for solo cello with piano, harp, vibraphone and celeste. Opera might have seemed to be beyond Clementi's reach, but he was keenly interested in the medium. His two music-theatre works – Es (1980) and Carillon (1992) – deal with two dramatic situations, perhaps the only two, that seem peculiarly well-suited to his idiom: inescapable obsession, and paralysis of the will.

These themes reflect his own situation, of a man driven to create in a world where creation had – in his view – become almost impossible. While some responded to this dilemma with gestures of despair, Clementi's modesty, irony and endless patience wrung from it a special kind of beauty. It is a heartening achievement, for which triumph is not too strong a word.

From 1971 to 1992, Clementi taught music theory at Bologna University. He is survived by his wife Brigitte, daughter Anna and son Mario.