Tony Abbott’s paid parental leave (PPL) policy is perhaps the policy with which he is most entwined. His statements have been so fixed and constant that any drop or alteration to them would be a serious blow to his policy credentials.

As such it deserves close scrutiny. Does it really deliver its proposed benefits? Is it really fully funded?

Abbott continually (and rightly) asserts that paid parental leave is a productivity and participation measure. That is, it hopes to increase the number of women staying in the workforce and that, as a result, the overall labour force will be more productive. It is mentioned in the Liberal party’s Real Solutions policy document under the heading “Improving productivity by boosting participation”. So will it actually boost participation?

The Liberal party’s PPL scheme is pitched as being (in the oft-said words of Abbott) “fair dinkum”, because it will pay the full replacement wage (up to $150,000 per annum) of the mother for 26 weeks, rather than the current scheme, whereby the mother receives the minimum wage $622.10 per week for 18 weeks.

There are thus two differences between the two schemes: the length of leave and the amount of money paid.

The government chose its scheme on the back of a 2009 report by the Productivity Commission (PC).

It recommended 18 weeks of leave even though it acknowledged that most mothers preferred to spend at least the first 26 weeks with their baby before going back to work.

The PC chose 18 weeks because this period would allow those who do wish to take extra leave to “co-fund” the extra amount through annual leave or through savings. It argued around 90% of families would find this option “affordable”.

The PC noted however, that while more leave might be better, in terms of overall benefit to the economy, at some point the “benefits would not be worth the additional costs of forgone spending in other areas such as higher quality childcare or a better health system”.

This is an important point when you consider how essential childcare is for women returning to work (and thus participation in the labour force).

The PC also noted that “the impact of the scheme on leave durations ... is greater for lower income, more financially constrained families”. It was concerned mostly about women who earn less because “they often have low representation in privately negotiated paid parental leave schemes”.

The Liberal party’s policy is of most benefit to those on high incomes, but the biggest issue of paid parental leave is actually for women on low incomes. Currently about 35% of all working women earn the minimum wage or less, but those workers only constitute 16% of working women with paid parental leave entitlements.

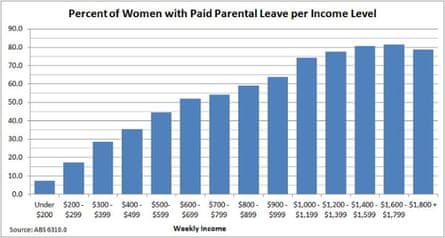

The higher you earn, the very much more likely you are to have a job with paid parental leave:

Clearly the benefits of a government providing parental leave at replacement income levels decline as the income of the mother increases – because it is more likely that their employer is already offering parental leave.

The PC found that a scheme such as the current one in place would “mean that the labour supply effects would be greatest for lower income, less skilled women – precisely those who are most responsive to wage subsidies and who are least likely to have privately negotiated paid parental leave”. This means the spending of government money would get the biggest productivity and participation bang for its buck by paying the minimum wage rather than a replacement wage.

So what did the Productivity Commission say about the participation benefits of the Liberal party’s scheme?

It found that that a scheme with “full replacement wages for highly educated, well-paid women would be very costly for taxpayers”. Now you might think that is OK if it improves participation, after all that is the aim of the scheme. However the PC noted that such women already had a “high level of attachment to the labour force” and that (as the above graph shows) such workers already had “a high level of private provision of paid parental leave”.

All up, the PC concluded with damning understatement that PPL “would have few incremental labour supply benefits”. It may provide a small boost to participation but it is certainly not worth the cost.

It should probably give you some pause when your party’s big-ticket policy for improving productivity and participation in the labour market has the Productivity Commission saying at best its benefits would be “few”.

Especially when we get to the cost.

When it was first introduced the scheme was to be offset by a “modest” 1.7% increase in the company tax rate of those earning over $5m. By the 2010 election the levy was down to 1.5% and the cost was rising from $4.3bn for 2012-13 to $4.5 bn for 2013-14.

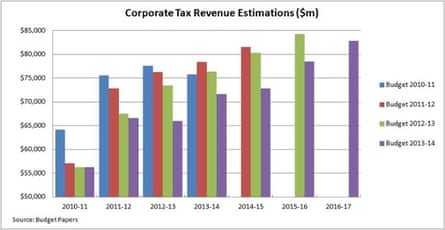

The problem, however, is since then company tax revenue has rather collapsed:

Back in the 2010-11 budget, corporate tax revenue for this current financial year was forecast to be over $75bn; in this year’s budget it was forecast to be only $71.6bn. The writedowns from the 2011-12 budget are even more severe. Back then, $81.5bn in company tax revenue was expected to be raised in 2014-15; now, the Treasury is expecting just $72.8bn.

Clearly a 1.5% levy on the top 3,200 companies is not going to deliver what was expected back in the 2010 election. And yet the 1.5% levy remains the only stated means the opposition has to pay for the scheme.

The rumours now are that the opposition might put off the scheme until the final year of the next term (if they win) or maybe cut out state public servants.

But at present they have a productivity and participation policy that doesn’t do much to lift either, and one that is supposed to be paid for by a bucket of money that has become a touch more shallow.

Given how inexorably linked this particular policy is with Tony Abbott, and given Andrew Robb stated in May that it was “fully funded”, it might be time we started seeing the costings. At present, analysis of the policy finds it lacking on both the costs and the benefits.