Abstract

Summary

Daily consumption of 50 g of dried plum (equivalent to 5–6 dried plums) for 6 months may be as effective as 100 g of dried plum in preventing bone loss in older, osteopenic postmenopausal women. To some extent, these results may be attributed to the inhibition of bone resorption with the concurrent maintenance of bone formation.

Introduction

The objective of our current study was to examine the possible dose-dependent effects of dried plum in preventing bone loss in older osteopenic postmenopausal women.

Methods

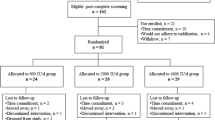

Forty-eight osteopenic women (65–79 years old) were randomly assigned into one of three treatment groups for 6 months: (1) 50 g of dried plum; (2) 100 g of dried plum; and (3) control. Total body, hip, and lumbar bone mineral density (BMD) were evaluated at baseline and 6 months using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Blood biomarkers including bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BAP), tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP-5b), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and sclerostin were measured at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. Osteoprotegerin (OPG), receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), calcium, phosphorous, and vitamin D were measured at baseline and 6 months.

Results

Both doses of dried plum were able to prevent the loss of total body BMD compared with that of the control group (P < 0.05). TRAP-5b, a marker of bone resorption, decreased at 3 months and this was sustained at 6 months in both 50 and 100 g dried plum groups (P < 0.01 and P < 0.04, respectively). Although there were no significant changes in BAP for either of the dried plum groups, the BAP/TRAP-5b ratio was significantly (P < 0.05) greater at 6 months in both dried plum groups whereas there were no changes in the control group.

Conclusions

These results confirm the ability of dried plum to prevent the loss of total body BMD in older osteopenic postmenopausal women and suggest that a lower dose of dried plum (i.e., 50 g) may be as effective as 100 g of dried plum in preventing bone loss in older, osteopenic postmenopausal women. This may be due, in part, to the ability of dried plums to inhibit bone resorption. This clinical trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02325895.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- TRAP-5b:

-

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-5b

- BAP:

-

Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase

- 25-OH vitamin D:

-

25-hydroxy vitamin D

- IGF-1:

-

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- hs-CRP:

-

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- RANKL:

-

Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand

- OPG:

-

Osteoprotegerin

- SOST:

-

Sclerosteosis gene

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- P1NP:

-

Procollagen type 1N-terminal propeptide

- CTX:

-

Collagen type 1 C-telopeptide

References

Colón-Emeric CS, Saag KG (2006) Osteoporotic fractures in older adults. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 20(4):695–706

Looker AC, Melton LJ, Harris TB, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA (2010) Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005–2006 compared with NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 25(1):64–71

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A (2007) Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22(3):465–75

Sambrook PN, Chen JS, Simpson JM, March LM (2010) Impact of adverse news media on prescriptions for osteoporosis: effect on fractures and mortality. Med J Aust 193(3):154–6

Reid IR (2015) Short-term and long-term effects of osteoporosis therapies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11(7):418–28

Cúneo F, Costa-Paiva L, Pinto-Neto AM, Morais SS, Amaya-Farfan J (2010) Effect of dietary supplementation with collagen hydrolysates on bone metabolism of postmenopausal women with low mineral density. Maturitas 65(3):253–7

Moyer VA (2013) Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 158(9):691–696

Ferrari CK (2007) Functional foods and physical activities in health promotion of aging people. Maturitas 58(4):327–39

Deyhim F, Stoecker BJ, Brusewitz GH, Devareddy L, Arjmandi BH (2005) Dried plum reverses bone loss in an osteopenic rat model of osteoporosis. Menopause 12(6):755–62

Arjmandi BH, Lucas EA, Juma S, Soliman A, Stoecker BJ, Khalil DA, Smith BJ, Wang C (2001) Dried plums prevent ovariectomy-induced bone loss in rats. JANA 4(1):50–6

Bu SY, Lucas EA, Franklin M, Marlow D, Brackett DJ, Boldrin EA, Devareddy L, Arjmandi BH, Smith BJ (2007) Comparison of dried plum supplementation and intermittent PTH in restoring bone in osteopenic orchidectomized rats. Osteoporos Int 18(7):931–42

Franklin M et al (2006) Dried plum prevents bone loss in a male osteoporosis model via IGF-I and the RANK pathway. Bone 39(6):1331–42

Arjmandi BH, Khalil DA, Lucas EA, Georgis A, Stoecker BJ, Hardin C, Payton ME, Wild RA (2002) Dried plums improve indices of bone formation in postmenopausal women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 11(1):61–68

Hooshmand S, Chai SC, Saadat RL, Payton ME, Brummel-Smith K, Arjmandi BH (2011) Comparative effects of dried plum and dried apple on bone in postmenopausal women. Br J Nutr 106(06):923–930

Mühlbauer RC, Lozano A, Reinli A, Wetli H (2003) Various selected vegetables, fruits, mushrooms and red wine residue inhibit bone resorption in rats. J Nutr 133(11):3592–3597

Vinson JA J, Zubik L, Bose P, Samman N, Proch J (2005) Dried fruits: excellent in vitro and in vivo antioxidants. Am Coll Nutr 24(1):44–50

Rendina E, Hembree KD, Davis MK, Marlow D, Clarke SL, Halloran BP, Lucas EA, Smith BJ (2013) Dried plum’s unique capacity to reverse bone loss and alter bone metabolism in postmenopausal osteoporosis model. PLoS One 8(3):e60569

Hooshmand S, Kumar A, Zhang JY, Johnson SA, Chai SC, Arjmandi BH (2015) Evidence for anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties of dried plum polyphenols in macrophage RAW 264.7 cells. Food Funct 6(5):1719–25

Bu SY, Hunt TS, Smith BJ (2009) Dried plum polyphenols attenuate the detrimental effects of TNF-alpha on osteoblast function coincident with up-regulation of Runx2, Osterix and IGF-I. J Nutr Biochem 20(1):35–44

Rendina E, Lim YF, Marlow D, Wang Y, Clarke SL, Kuvibidila S, Lucas EA, Smith BJ (2012) Dietary supplementation with dried plum prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss while modulating the immune response in C57BL/6J mice. J Nutr Biochem 23(1):60–8

Hooshmand S, Brisco JR, Arjmandi BH (2014) The effect of dried plum on serum levels of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand, osteoprotegerin and sclerostin in osteopenic postmenopausal women: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr 112(1):55–60

Szulc P, Bauer DC, Eastell R (2013) Biochemical markers of bone turnover in osteoporosis, in primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp 297–306

Bolarin D (1996) Biochemical markers for the assessment of skeletal growth in children. Nig Quart J Hosp Med 6:256–261

Gundberg C, Looker AC, Nieman SD, Calvo MS (2002) Patterns of osteocalcin and bone specific alkaline phosphatase by age, gender, and race or ethnicity. Bone 31(6):703–708

Simonavice E, Liu PY, Ilich JZ, Kim JS, Arjmandi BH, Panton LB (2014) The effects of a 6-month resistance training and dried plum consumption intervention on strength, body composition, blood markers of bone turnover, and inflammation in breast cancer survivors. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 39(6):730

Seeman E, Nguyen TV (2015) Bone remodeling markers: so easy to measure, so difficult to interpret. Osteoporos Int.

Mubarak A, Swinny EE, Ching SY, Jacob SR, Lacey K, Hodgson JM, Croft KD, Considine MJ (2012) Polyphenol composition of plum selections in relation to total antioxidant capacity. J Agric Food Chem 60(41):10256–62

Hooshmand S, Arjmandi BH (2009) Viewpoint: dried plum, an emerging functional food that may effectively improve bone health. Ageing Res Rev 8(2):122–127

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable assistance of the following students at San Diego State University: Mariana Beleche, Sofie Blicher, Jayme Brisco, Bich Thuy Callens, Zachary Clayton, Amanda Cravinho, Jennifer Cullison, Sofia Garcia, Jackie Gaylis, Montserrat Gonzalez, Mairi McLachlan, Tasnim El Mezain, Rose Miller, Ivette Navarro, Dawn Ortiz and, Yenina Vereda. This project was supported by the SDSU Research Foundation grant no. 242409 and a grant from the California Dried Plum Board (grant no. 57114A). The authors thank the California Dried Plum Board for providing us with dried plums and we gratefully acknowledge Nutrisystem, Inc. supplying calcium and vitamin D supplements for the study. The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: SH, MK, and BHA designed the research; SH, DM, and PS conducted the research; SH, MK, and SCC analyzed data; MEP performed statistical analysis; SH, DM, PS, SAJ, and BH wrote the paper; MK, SAJ, and BHA had substantial involvement in manuscript revision before submission; SH had primary responsibility for final content. All authors edited and approved the final version. Shirin Hooshmand, Dina Metti, Pouneh Shamloufard, Mark Kern, Bahram H. Arjmandi, Sheau C. Chai, Sarah A. Johnson, and Mark E. Payton declared that they had no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The Institutional Review Board at San Diego State University approved all procedures involving human subjects. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hooshmand, S., Kern, M., Metti, D. et al. The effect of two doses of dried plum on bone density and bone biomarkers in osteopenic postmenopausal women: a randomized, controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 27, 2271–2279 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3524-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3524-8