Fake news is why you exist. And 12 tools that can help

Okay. Basic question.

“If I asked you to describe what you do every day as a social studies teacher, what would I hear?”

Let me rephrase that a bit.

“If I asked you to describe what you should be doing every day as a social studies teacher, what would I hear?”

Here’s my point. I think that we can get so caught up in the everyday that we sometimes forget why we exist. Grading papers. Taking roll. Going to meetings. Calling parents. Trying to keep middle school kids from setting things on fire. That’s a typical day in your life. I get that.

But I’m going to suggest today that we need to keep our eyes on the prize.

What’s the prize? Why do we exist?

The National Council for the Social Studies College, Career, and Civic Life Standards does a pretty good job of summing it up:

(We are all) bound by the common belief that our democratic republic will not sustain unless students are aware of their changing cultural and physical environment; know the past, read, write, and think deeply; and act in ways that promote the common good. The goal of knowledgeable, thinking, and active citizens . . . is universal.

Now more than ever, students need the intellectual power to recognize societal problems; ask good questions and develop robust investigations into them; consider possible solutions and consequences; separate evidence-based claims from parochial opinions; and communicate and act upon what they learn. And most importantly, they must possess the capability and commitment to repeat that process as long as is necessary.

Need a short answer?

Kids who can think critically, using a variety of corroborating and supporting evidence in order to solve authentic problems so that the world is a better place.

Sam Wineburg distills it down even more:

I know you know this. Consider this a gentle reminder that there is a confusing world out there and it doesn’t really care whether your kids are able to “thoughtfully engage in information seeking and gathering.” In fact, I’m going to suggest that there are many out there – I’m looking at you fake news guy – who would actually prefer that your kids don’t possess those kinds of skills at all.

As we become more aware of the prevalence of fake news and sketchy journalism, it’s more important than ever for us to stay focused on our task of preparing students to be effective evaluators of evidence.

I love that teachers and students can access primary sources from the Library of Congress and National Archives. I love that we can read all sorts of secondary sources online including up to the minute coverage of events around the world. But this sort of access doesn’t mean much if students aren’t able to tell the difference between these valid sources and the huge amount of unintentional and intentional misinformation available online.

A recent Quartz article by Marie Myung-Ok Lee highlights why our task is so vital:

Today, in a time of economic uncertainty, many students are being encouraged to skip history and other liberal arts classes in favor of a practical STEM focus. But (the rise of fake news during) this election has shown that nothing could be more practical for Americans than a deep immersion in our country’s history.

Do we want higher education merely to produce workers, or do we want students equipped with the skills to understand, question, create? History does much more than prepare people to become professional historians. It teaches us how to think – that is, how to do the high-level analysis that is essential for an informed society. It requires analysis of data and deep research, as well as the use of archival and primary sources. Such skills are absolutely critical in an era that is increasingly characterized by the relentless bombardment of information.

And it’s not just fake news – paid protesters in Austin, Texas, criminal activity in a DC pizza parlor, a KKK Minnesota sheriff, or the Pope supporting President-Elect Trump – being peddled as actual events. (Before we go further, though, a definition of terms. A recent Leonard Pitts article suggested that fake news should “not to be confused with satirical news as seen on shows like ‘Saturday Night Live’ and ‘Last Week Tonight.’ Fake news is not a humorous comment on the news. Rather, fake news seeks to supplant the news, to sway its audience into believing all sorts of untruths and conspiracy theories, the more bizarre, the better.”)

It’s not just fake news, it’s our inability to detect and evaluate historical claims as well.

Take, for example, the history textbook titled Our Virginia: Past and Present by Joy Masoff. The Civil War chapter included a statement that “thousands of Southerner blacks fought in Confederate ranks, including two battalions under the command of Stonewall Jackson.” This myth of the Confederate black soldier tracks back to the late 1970s and “a small group of Confederate heritage advocates who hoped to distance the history of the Confederacy from slavery.”

The argument? If free and enslaved men fought as Confederate soldiers, than it would be impossible to suggest that the Confederacy fought to protect the institution of slavery. No historian supported these claims. The publisher and Masoff later claimed to have found the information on a Sons of Confederate Veterans website. There are scores of sites claiming the same thing containing “primary sources” that appear legitimate. This sort of online content packaged as historical fact present our students with the same challenges as fake news sites.

A recent Stanford study measured students’ ability to assess evidence and information, describing the results as

dismaying, bleak, and a threat to democracy.

Researchers spent a year asking over 7800 middle, school, high school, and college students to evaluate online information presented in Tweets, comments, and articles. And it’s not like Stanford was asking kids to do any sort of high level analysis. They were looking for the ability (what researchers called a reasonable bar) of “telling fake accounts from real ones, activist groups from neutral sources, and ads from articles.”

So how’d they do? Students displayed a

stunning and dismaying consistency in their responses.

Many assume that because young people are fluent in social media they are equally savvy about what they find there. Our work shows the opposite.

Some basic findings based on the research:

- Most middle school students can’t tell sponsored ads from articles.

- Most high school students accept photographs as presented, without verifying them.

- Many high school students couldn’t tell a real and fake news source apart on Facebook.

- Most college students didn’t suspect potential bias in a tweet from an activist group.

- Most Stanford students couldn’t identify the difference between a mainstream and fringe source.

(You can explore examples of what students were asked to do with sample responses to get a more in-depth view at the study’s executive summary.)

Sam Wineburg, part of the Stanford History Education Group, commented on the research:

What we see is a rash of fake news going on that people pass on without thinking. And we really can’t blame young people because we’ve never taught them to do otherwise.

We can do better. We need to do better.

Part of the solution, of course, is to teach kids to read like fact checkers. Similar sorts of things we’re already asking them to do with primary sources and other sorts of evidence. So kids need to be sourcing, contextualizing, and corroborating online information much the same way. This becomes especially important as we ask kids to use online search engines such as Google that don’t rank search results by reliability. (And whose search algorithms are being gamed by a variety of unreliable sources.)

Wineburg continues:

The kinds of duties that used to be the responsibility of editors, of librarians now fall on the shoulders of anyone who uses a screen to become informed about the world. And so the response is . . . to teach them how to thoughtfully engage in information seeking and evaluating in a cacophonous democracy.

So. What to do?

Keep your eyes on the prize. Develop lessons and units that create students who “can think critically, using a variety of corroborating and supporting evidence in order to solve authentic problems so that the world is a better place.” Training kids to think historically not only helps kids make sense of the past but also prepares them to better evaluate the present.

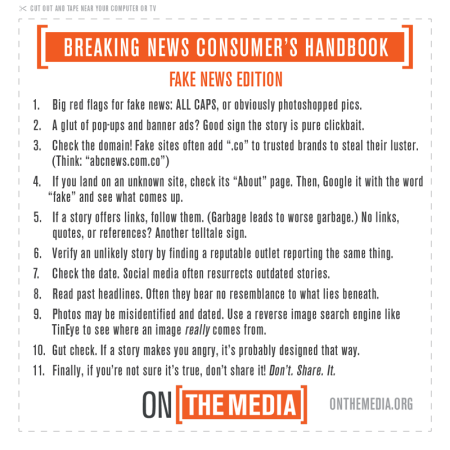

Need some specifics? Check out these handy tools:

I would probably start with this chart that Vaness Otero, an attorney in Denver, developed. It’s a helpful visual that could be a geat way to start the conversation about historical thinking and evaluating evidence.

Of course, I can hear some of you already.

The chart is biased. That source should be over here. Or there. Or not on the chart at all.

But that’s kind of the point. Part of the historical thinking process is corroboration. So you or your kids disagree with where your favorite news source is placed? Find evidence at multiple sources from the middle third of the chart that support and corroborate the information that I can get from your favorite. If the only place students can find supporting evidence is from the same right or left third of the chart as the original article, it’s likely an article that can’t be trusted.

Have kids select a news event and ask them to take screenshots from websites from different quadrants to compare and contrast how the same event is covered. Send kids to the Newseum Front Pages site for different newspapers to corroborate and refute. (The NewseumEd site has all sorts of handy tools .)

Perhaps have students do close reading exercises of articles from different thirds of the chart – picking out and charting the adjectives and descriptive language found in each, color coding where each of those words were found. Talk about what inflammatory, sensational, and emotional mean. Have students swap charts and ask them to highlight the inflammatory, sensational, and emotional words on their partner’s chart. Then swap back and have the original student label the color coded words by the news source. Where on the chart does this news source fall? Is there a connection between where on the chart the news source falls and the number of inflammatory, sensational, and emotional words connected to that source?

Then head to an article by Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew titled Why Students Can’t Google Their Way to the Truth. They provide three simple steps that professional fact checkers practice and that the rest of us need to perfect:

- Landing on an unfamiliar site, the first thing checkers did was to leave it

If undergraduates read vertically, evaluating online articles as if they were printed news stories, fact-checkers read laterally, jumping off the original page, opening up a new tab, Googling the name of the organization or its president. Dropped in the middle of a forest, hikers know they can’t divine their way out by looking at the ground. They use a compass. Similarly, fact-checkers use the vast resources of the Internet to determine where information is coming from before they read it. - Second, fact-checkers know it’s not about “About”

They don’t evaluate a site based solely on the description it provides about itself. If a site can masquerade as a nonpartisan think tank when funded by corporate interests and created by a Washington public relations firm, it can surely pull the wool over our eyes with a concocted “About” page. - Third, fact-checkers look past the order of search results

Instead of trusting Google to sort pages by reliability (which reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how Google works), the checkers mined URLs and abstracts for clues. They regularly scrolled down to the bottom of the search results page in their quest to make an informed decision about where to click first.

You’re going to find some helpful definitions and suggestions for evaluating information at How to Outsmart Fake News in Your Facebook Feed.

The News Literacy Project is an awesome place for teaching tools. Their stated mission – “an innovative national educational program that mobilizes seasoned journalists to work with educators to teach middle school and high school students how to sort fact from fiction in the digital age” is perfect for what we’re trying to do here. Use their tools and the following worksheets as part of your lesson design:

Richard Byrne of Free Technology For Teachers shared a Real or Fake Google Search Challenge developed by Dan Russell that can help students use search tools more effectively.

KQED has a nice article with a lesson plan and resources at The Honest Truth about Fake News . . . and How Not to Fall for It.

Truth, truthiness, triangulation: A news literacy toolkit for a “post-truth” world is a great post from Joyce Valenza on the School Library Journal’s website. You find video clips, handouts, and suggested activities.

Melissa Zimdars, an associate professor of communication and media at Merrimack College in Massachusetts, published a Google Doc with some tips and a six step process for evaluating online news sources.

This multiple page Google Doc, from Howard Rheingold, titled Crap Detection Resources has over 100 online tools that can help detect bias in a variety of mediums. (Full disclosure – Rheingold seems to be unaffiliated but has written several books on Internet / digital literacy and his list looks useful. I’ll let you and your students decide how useful.)

Updated resources:

Identifying Fake News: An Infographic and Educator Resources from EasyBib

How to Choose Your News lesson plan and video from TedEd

Evaluating Sources in a ‘Post-Truth’ World: Ideas for Teaching and Learning About Fake News from the New York Times Learning Network

Newsela Text Set: The Phenomenon Of Fake News

PBS – How to Teach Your Students About Fake News

Adapt and modify any or all of these tools. Because we can and need to do better.

——

Updated with new tools 2/7/2017. Find them at the bottom of the post.

Great resource. Thanks so much for sharing this.

Hope it’s useful!

glennw

Excellent information! Thanks for putting this together.

Great source of information to sift through the nonsense. Where I’ve seen as a prevalent symptom of fake news is that commentators or partisan groups on social media will repost without fully identifying the source.

Jack,

You’re right! We all jump too fast when reposting or forwarding things. One of the simplest things we can teacher ourselves and our kids is to count to ten first.

Have a great weekend!

glennw