This week the largest comics festival in France announced its 30 nominees for what many consider the most prestigious prize in comics, the Grand Prix. Not one nominee was a woman.

Usually there are at least few women on the longlist for the Angoulême International Comics Festival (known in French as the Festival international de la bande dessinée or FIBD). Last year’s list included only Marjane Sartrapi. In fact, in the festival’s 43-year history, there has only been one female Grand Prix winner: Florence Cestac, who got the prize in 2000. But this year, there was a swift reaction.First, inspired by the French group BD Égalité, or Women in Comics Collective Against Sexism, 12 nominees dropped out of consideration, among them Daniel Clowes, Riad Sattouf, Brian Michael Bendis and Chris Ware. FIBD then added six women to the original list of 30 nominees. Then it dropped the list altogether, declaring that academy members could vote for whomever they chose, and the festival would “submit to the absolute free will” of its members.

To make matters worse, in a remarkably tone-deaf interview, the executive officer of the festival, Franck Bondoux, claimed that there was a very simple reason no women were included among the nominees. Discrimination was not to blame, he said. Instead, it was because of a lack of qualified women. “The Festival likes women, but cannot rewrite the history of comics,” he said.

Bondoux cited the history of art in support. “If you go to the Louvre,” he said, “you will find few women artists.”

Yet the art world knows there are historic reasons for a lack of women in the limited period that the art at the Louvre represents. Women were barred from the academic training that was considered necessary for success. But when you look at the modern artistic landscape, it’s impossible not to see that the art world is trying to correct this oversight.

“For over 100 years, we have seen the presence of women in the American comics,” Caitlin McGurk, the associate curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library (which houses the largest collection of comics and comic-related history in the world), said.

“For the first half of the 20th century, many female cartoonists wrote under ambiguous or masculine names, just to increase their likeliness for publication.”

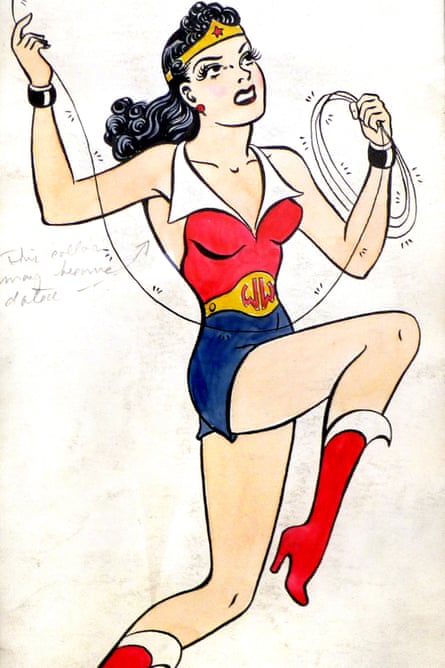

McGurk has many examples: June Mills, who went by a version of her middle name, “Tarpé”, when she created the great Miss Fury in 1941. Miss Fury, in fact, was the first female action hero created by a woman, predating Wonder Woman.

“The early days of the comic strips saw national syndication for artists like Grace Drayton, Rose O’Neill, Nell Brinkley, Ethel Hays, and more who created, published and thrived even under their given name in the first few years of the 1900s,” McGurk continued.

She also cited Edwina Dumm, the first female political cartoonist in the United States, who was working long before suffrage had even been extended to women, and Lou Rogers, the art director for Margaret Sanger’s groundbreaking and controversial Birth Control Review.

Women were also a substantial presence in the underground comics movement, he said. “How can we dismiss the liberating works of Trina Robbins, Joyce Farmer, Carol Tyler, Roberta Gregory, Diane Noomin?”

“And so many who have followed in their footsteps – from Lynda Barry to Phoebe Gloeckner, Marjane Sartrapi and more. These women paved the way for the substantial variety of female cartoonists whom we see working in the field today – their presence is not a token anomaly.

“What frightens and disappoints me most about the lack of recognition these women have received, however, is actually the lack of education and historical familiarity present in those who are given the power to bestow such acknowledgements.”

Tom Spurgeon, the writer of the Comics Reporter and the executive director of the Cartoon Crossroads Columbus, an American comics festival, certainly disagreed with Bondoux’s pronouncement.

“It’s actually very easy to rewrite the history of comics.” Spurgeon said. “It happens all the time. You rewrite history by putting people on these lists. That history failed Angoulême is a terrible, cynical argument to make. The listmakers weren’t even asked to look at history. They were asked to survey the present. Zero for 30 is a dismal reading of the present.”

Spurgeon is right. Off the top of my head, I can give you the names of a dozen female comics writers deserving of a lifetime achievement award right now. There are the women of the Japanese manga collective Clamp, whose work ranges from the mythic shojo (girls manga) RG Veda to the seinen manga (adult men’s manga) Chobits. Their output dwarfs all but the most prolific of creators, with their influence seen in comics and cartoons worldwide.

There’s also Alison Bechdel, whose 30 years of weekly Dykes To Watch Out For strips stand next to her two bestselling graphic novels, her MacArthur Genius award and the Broadway musical based on her work.

And closer to the festival’s home there’s French comics titan Claire Bretécher whose work skewering outdated gender stereotypes has appeared in French humor magazines, in 23 published collections and on French television. (She received a special award from FIBD in 1983, but has never been given the actual Grand Prix.)

Other areas of the comics world have managed to get past attitudes like Bondoux’s. The Eisner Awards, awarded at the San Diego Comic Con since 1988 and often referred to as “the Oscars of the comics industry”, had its first female winner in 1992, when Karen Berger won for her work as editor on Sandman.

In fact, many modern comics festivals have fallen over themselves to award female comics creators. Just in the last year, an all-female slate swept the Ignatz awards at the Small Press Expo in Maryland. If anything, the number of female award winners at festivals in the last few years has been overwhelming.

In fact the one bright light to this whole affair is that Bondoux’s blind spot to women’s contributions to comics history may end up costing FIBD more than just their reputation. As author Bart Beaty pointed out, the Grand Prix winner stands for more than just merit. It’s risky for any festival to ignore 50% of the population when it comes to its greatest prize.

Even a prestigious festival may have problems attracting a modern audience with such retrograde ideas. To represent the best of comics today, people whose history may have been ignored or discounted needs to be included. Hopefully Bondoux and the FIBD will see this controversy as a reason to change course and embrace the diversity of comics, past and present.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion