It wasn’t just that Rachel Whiteread was moving house, it was that she was leaving Shoreditch, east London, the last artist standing, responsible for turning off the lights. “Shoreditch, my great love,” she sighs, wistful. She left a year ago, relocating with her husband and two sons to north London, a journey that takes half an hour in the car but, probably, around a decade in therapy.

To enter her new studio in Camden, visitors must squeeze through a low doorway cut into a garage, then carefully descend a single-file staircase. And then, from that tiny darkness, you go through a final door and stand, blinking, in a church of a space, an almost triple-height room that smells of coffee and cultivated peace. On the walls are casts in paper. When Whiteread moved in, she tried to get rid of as much of her collected ephemera as possible. She was left with a single plan chest of drawings, and it weighed on her. So she bought three shredders and turned the lot into papier mâché, which she cast on corrugated iron. Today they hang beside her desk, an abstract archive of a 30-year-old career.

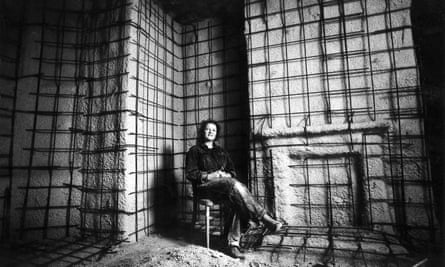

It’s 24 years since Whiteread, then 30, cast the last remaining property in a demolished terrace in Bow, east London, in liquid concrete, sparking debates about the upheaval of the East End, the politics of “regeneration”, and the point of contemporary art. On the day in 1993 that Whiteread became the first woman to win the Turner Prize, the decision was made to demolish the house.

That afternoon she got a call from Bill Drummond of the K Foundation telling her she had been voted their worst artist in the world, and had won a prize of £40,000, double the Turner Prize money. They blackmailed her, she said. If she didn’t leave the Turner party to receive the cash, it would be destroyed. She accepted, donating some of the money to young artists and the rest to Shelter; a televised interview from the following day shows her wide-eyed and knackered, and unready for such attention. Along with Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst, Whiteread became one of the Young British Artists who gave contemporary art in the 1990s that mass appeal. Though she shudders at the thought, they made art fashionable.

A side effect of that Brit Art boom, with its grimy glamour, was that a spotlight fell on east London where they worked, helping transform it into the “hipster” biodome it is today. As she talks about leaving the area, it’s easy to doodle connections between Whiteread’s process of casting buildings – inverting a home (complete with outlines of fireplaces, windows and staircases) and turning it into a machine for not living in– and the process of gentrifying Shoreditch. What was, in the 1990s, a diverse community of artists and immigrants is today mainly empty apartment blocks, bars and the odd branding agency.

“Twenty years ago we bought and converted an old synagogue, but the area changed. Nobody lives there now,” Whiteread says. “They call it the ‘art effect’. Foxtons sniff around the artists, because they’re resourceful people, pioneers, who find the interesting seed of a place, and that energy and creativity grows until they price themselves out.”

She wears a buttoned-up navy worker’s jacket, her hand resting inside, on her collar bone. “We gradually got sick of buskers at three in the morning, coach parties surrounding our house, the constant fight about what would be built opposite us. The studio vibrated – it wasn’t good for my mental health. So we moved to find some peace. And we miss it, but not as much as we thought we would.”

She sips her coffee. “I’m affected by my environment, and I love the new light, the quiet, not feeling under siege by… youth.” Does she feel guilty? She snorts. “Guilty! For changing Shoreditch? No. We bought a weird building that had been empty for years, and it took people like us to work out a way of living there.”

She’s been spending a lot of time back in east London this week, as she installs a permanent piece at the Museum of Childhood. It’s a place she’s loved all her life – she remembers the long drive in her dad’s car to Bethnal Green from Ilford, to marvel at the doll’s houses in their glass cases. From Essex the family moved to north London, where at seven years old she helped build a studio in the basement for her mum Pat, a feminist artist. Despite an A Level attempt at science, Whiteread found herself following in her mother’s footsteps, and went to Brighton, and then the Slade, to study art.

“Over the years,” she says, “through my interest in sculpture and architecture I started to buy the odd doll’s house, then thought about lighting them, and it became a bit obsessive – I started to see doll’s houses everywhere. These amazing parcels arrived from eBay, the extraordinary way people packaged them. And when I unwrapped them, it became a village.” She donated the work to the museum, where it will live in a dark corner, a hillside of crates, the houses lit from within. “It’ll be a spectacle,” she promises. A quieter, more intimate spectacle than her huge plaster sculptures, but one that similarly reverses a space, the tiny lights revealing emptiness. “Doll’s houses can be really creepy, of course, these ones even smell like real houses, that mustiness. Some look like there are people buried in the back garden, they’re not sweet in any way. It’s a sinister village. Which means, when you walk in, hopefully you’ll remember it for ever.”

Whiteread is still close to many of her 90s contemporaries – they have a running joke about building an old people’s home for YBAs. But her chuckle turns into a groan. “Artists now live a very different life to the ones we lived. We had no expectations, we played hard and worked hard. Now they expect a career, they expect fame. I stopped teaching because of that. It seemed students were only interested in being famous.” Perhaps the YBAs did to art what they did to Shoreditch. “We made it look too easy,” says Whiteread. “Art was slower then, and better because of it. It wasn’t immediate. You couldn’t ‘yes or no’ something on Instagram. You had to travel to see it, which makes for a more thoughtful response.”

Are there any great artists emerging now? She scrunches her nose. “I don’t know. I rarely go round the galleries these days, partly because I’m sick of it. I just like my own stuff!” She doesn’t say this with malice. And she’s done plenty to support new artists, taking on a series of “protégés” whose lives she’s helped shape. In a pleasing twist, her role was recently reversed when her mentor Phyllida Barlow found success much later in life, “So I was able to repay the kindness, and help her.”

Whiteread has just submitted a proposal with her husband Marcus Taylor for the Holocaust memorial in London: they want to cast the existing monument to slavery, and in the space underneath install sound pieces, the walls whispering their memories. There’s also a huge piece she’s working on for the American embassy, the cast of a flatpack house, though she’s devastated it’s taken so long – she wanted it installed when Obama was in power. After filling the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern with 14,000 plastic boxes in 2005, she’s currently preparing for her Tate retrospective later this year. “Please don’t call it a retrospective,” she says – there is too much death implied. “I can only think about it if I call it a ‘survey’.” We walk through her studio, and I touch a set of oversized metal cutlery – enlarged from a doll’s house set, wobbly and uncomfortable.

The odd thing about what she calls her “shy sculptures” – a cast house on an island in New York, one in Norway, another in Norfolk, two in the desert – is that rather than their massiveness, the inversion makes you realise how small a home is, its limits. Whiteread doesn’t do many interviews, and she is reluctant to talk about something even as dinner-partyish as housing, but she will say: “I’m interested in homes, in the politics of housing, but I’m no expert. I simply think it’s everyone’s fundamental right to have a roof over their head. We should be helping everyone to make a life – London can absorb many groups of people.”

Her reticence sets her apart from other artists of her generation, with their broadcasting careers and lives that face outwards. “Art was never seen as a career when I was studying. Damien [Hirst] had a lot to do with changing the way people thought about it, with his ability to spin anything. People like Grayson Perry, who I shared a studio with back when he was still struggling, great show-offs who want to be in the media all the time… It’s not for me. Damien is a bit quieter now, but you see the residue of him. Tracey [Emin] too, these are people who have done a lot to be out in the world spinning a tale, making art an attractive proposition.”

She smiles shyly. “Early on I did a lot of TV, with a crew following me round, but I can’t be arsed with it now. I could have been the person that got the year-long contract with Channel 4, but I like being in the studio.” Does that media attention affect the work? “Well, in the end it must, mustn’t it – you’re always on show. I see Grayson making his Brexit pot online and I think… OK.” OK? A shrug. “People do what they need to do. I always think of Tracey as the girl in the playground shouting ‘Me me me!’ I’m very fond of her, but she plays on that and it seems to work. People love her for it.”

She is comfortably silent for a moment and, of course, it’s this silence, against the noise of her contemporaries, that people love her for. The political poetry of her work, her continuing crawls around the spaces we fill, the quiet, concrete search for home. “The mystery of being an artist is quite important I think, the privacy. I need and enjoy that, and spend time keeping hold of that.” She looks up at the window, then across, at her new cast of a window, and she’s had enough of being interviewed. She wants to get back to work. “It’s just… the way I am.” She looks at me. “Done?”

Rachel Whiteread’s Place (Village) is at the V&A Museum of Childhood from 25 March (vam.ac.uk)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion