How Bosnia is helping identify Cypriots murdered 50 years ago

- Published

In the 1960s and 1970s, hundreds of Cypriots disappeared. Now, there is a renewed effort to find out what happened to them - mass graves are being dug up and a laboratory in Sarajevo is helping to identify the bodies.

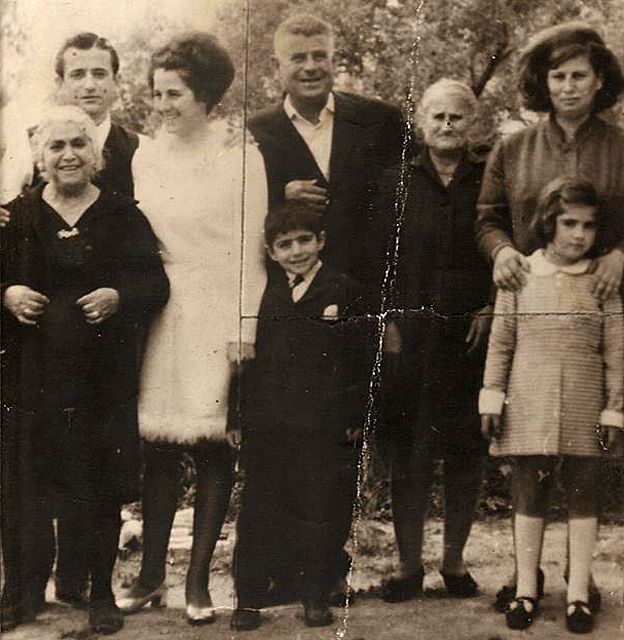

Forty years ago, Maria Georgiadis (above in the white dress), lost her whole family - her mother, her father, her sister and her brother. But she has never been able to lay their bodies to rest.

Georgiadis, a Greek Cypriot, was 28 years old at the time and was living in the capital of Cyprus, Nicosia, with her husband and two young children.

The rest of her family lived 10km away in Kythrea, but in August 1974 after a Greek-inspired coup and intervention by Turkish troops, their village became part of a Turkish-Cypriot enclave.

For two months, she tried to find out what had happened to her relatives. Eventually her fears were confirmed when she saw their names listed in a local newspaper - they had all been killed.

Chrystala (her mother, back row second from right), Andreas (her father, middle back row) Melitsa (her sister, back row far right) and Christy were four of 2,001 Greek and Turkish Cypriots who went missing in the early 1960s and 1970s - like hundreds of others, their bodies still haven't been found.

"It's as though something is missing. For a long time I was waiting for a knock on the door, for them to come in. Now I just want them to be in one place, where I can go and place some flowers," says Georgiadis.

Today, aged 69, with children and grandchildren of her own, she wants a proper funeral and a grave to visit where she can light a candle.

For years, the issue of the missing in Cyprus was mired in politics, and with little communication between Greek and Turkish Cypriots it wasn't until 2007 that they could even agree on an official list of who had disappeared.

Since then the UN-backed Committee of Missing Persons (CMP) - made up of a representative from both communities as well as UN representative Paul-Henri Arni, has been leading the search for burial sites and organising the excavation, exhumation and identification of bodies.

Since 2007, 571 bodies have been found, identified and returned to their families. That means the relatives of a further 1,430 missing Cypriots still wait for news.

"These things are very sensitive. We are dealing with people who didn't fall from a bicycle, but people who were killed… So it's normal that it takes a lot of time," says Arni.

With time running out for the remaining relatives, there is a renewed push to identify burial sites and speed up the identification of remains.

"I've seen women raped, detainees tortured, people losing limbs, their house, their country. All these sufferings of war can heal with time, but not if your son or father doesn't come home for dinner for 30 or 40 years. It's the only wound of war that gets worse with time," he says.

The CMP recently decided to tap into the expertise developed at a laboratory in Sarajevo. The centre in Bosnia Herzegovina specialises in extracting DNA from bone samples and matching them with genetic material from living relatives.

Run by the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), this laboratory was set up in 1996 after the war in the former Yugoslavia left 40,000 people missing.

The ICMP helped to identify almost 30,000 of them using DNA techniques, and since then has shared expertise with scientists in conflict zones and places hit by natural disasters around the world.

Now, as bodies are exhumed in Cyprus, bone samples are sent to Sarajevo for DNA matching.

In the conflicts in both countries, killers dumped bodies in mass graves, and then to try to hide their crimes, moved them, sometimes several times, to different sites. Remains were mixed up and the only way to reassemble the broken bodies so they could be identified was to use DNA.

In the former Yugoslavia, even when families buried incomplete bodies, further agony could follow when additional remains were then recovered.

"One lady described the hell of burying her son, one bone at a time," says Adam Boys, at the ICMP.

"It's heart breaking. They say, 'My son went away alive, and I want him back alive,' they can't accept it."

"One mother has in her fridge a jar of Nivea cream, wrapped up for protection in plastic bags. The only evidence her son exists is the fingerprint he left when he was taking cream out of the jar."

The CMP in Cyprus has family counsellors to support relatives over the years as they wait for news - each time a potential burial site is discovered, hopes are raised.

Georgiadis has been to five excavations. "Every time… my heart was beating in my breast and I was asking will it be now? But nothing. Still I hope that before I die I will be able to bury them.

"I have told my children, "If they are found after I die, please put their remains with me.'"

In January this year a mass grave was uncovered at a Cypriot stone quarry in Pareklissia near Limassol - families lined the hills above the site, hoping to see the bones of the men and teenage boys who had been abducted, taken from a bus and killed 40 years earlier.

So far, 35 bodies have been recovered from this site and partial remains sent to the Sarajevo laboratory for analysis.

"The skull is a very important body part to relatives," says Ziliha Uluboy, a clinical psychologist with the CMP.

"It's the face. When they don't see this they feel very bad."

In Cyprus, the CMP arranged immunity from prosecution for those who come forward with information about where the bodies of the missing are hidden.

But evidence is hard to come by. In some cases those involved in the killings are still alive and many people are afraid to talk.

As the decades pass, the physical landscape changes too, and it becomes harder and harder to locate hidden graves as memories fade and new building alters and sometimes obscures completely, burial sites.

One woman on the island, Sevgul Uludag, is credited by both the Greek and Turkish communities as having had a vital role, over the past 12 years, in finding the missing.

An investigative journalist with a popular blog, she carries two mobile phones - one for Turkish Cypriots and the other for Greek Cypriots to call her, anonymously, with information.

Uludag receives thousands of calls a year about possible burial sites - she alerts the CMP and investigations begin. She has helped locate hundreds of bodies.

But this voluntary, unpaid work has put her at risk and she's had death threats from people who carried out the killings and those trying to protect them.

"They said, 'We will shoot you from behind, we will break your legs, arms, cut your tongue. A car will come and hit you.' But I persisted because I knew once the barrier broke, information would flow in and it would bring relief to people," she says.

For Uludag, the fate of the missing people in Cyprus and the families waiting for them must not be reduced to just numbers.

"These are human faces, human feelings, Turkish Cypriot families, Greek Cypriot families - the same."

Cyprus divided

• 1960 - independence from British Rule leads to power sharing between Greek Cypriot majority and Turkish Cypriot minority

• 1963 and 1964 - inter-communal violence erupts

• 1974 - Cypriot President, Archbishop Makarios, deposed in a coup backed by Greece's military junta - Turkey sends troops to the island

• UN estimates that 165,000 Greek Cypriots fled or were expelled from the north, and 45,000 Turkish Cypriots from the south - 2001 officially people recorded missing

• 1975 - Turkish Cypriots announce establishment of their own state in the north, recognised only by Turkey

• 2007 - The Committee on Missing Persons in Cyprus begins excavations and exhumations of graves - 571 people identified by August 2014

After 44 years, Turkish Cypriots, Veli Beidoghlou and his sisters, Sifa and Muge, were, finally, able to lay their father, Arturo Veli, to rest.

In May 1964, when Veli Beidoghlou was just four, his father was abducted leaving their young mother a widow.

He had been the manager of Barclays Bank in what's now the abandoned town of Varosha near Famagusta.

In 2005, Sevgul Uludag told Beidoghlou that the CMP was excavating a mass grave down a dry well, in what used to be orange groves in the southern part of Famagusta.

Arturo's body was discovered with five others. He had been shot three times. One bullet wound was clearly visible in his head - the others were in his pelvis and torso.

The family knew it was him immediately - his wedding ring was still on his finger and they also recognised the tie hanging round his neck. But it took three years to work through the formal identification process.

Finally, in 2008, the family was able to bury Arturo in Nicosia cemetery, his grave alongside the other murdered men who'd been dumped down the same well.

For their mother, the discovery of his body was a deep shock.

"In the beginning she didn't want to believe it. There were flashbacks and memories freshened up, a lot of sadness - even though, at the same time it brings the relief of knowing," says Muge.

For Veli Beidoghlou too, finding their missing father has closed one chapter but opened another. "I know why he died, but I still want to know exactly how it happened," he says.

More from the Magazine

Varosha, where Arturo Veli worked, was once a popular seaside resort that attracted the rich and famous. Its residents fled 40 years ago and the place is now a ghost town.

Bereavement Without a Body is broadcast on BBC World Service at 19:30 BST on 1 October. You can also listen on iplayer or download the Health Check podcast here.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.