Why Sandy Has Meteorologists Scared, in 4 Images

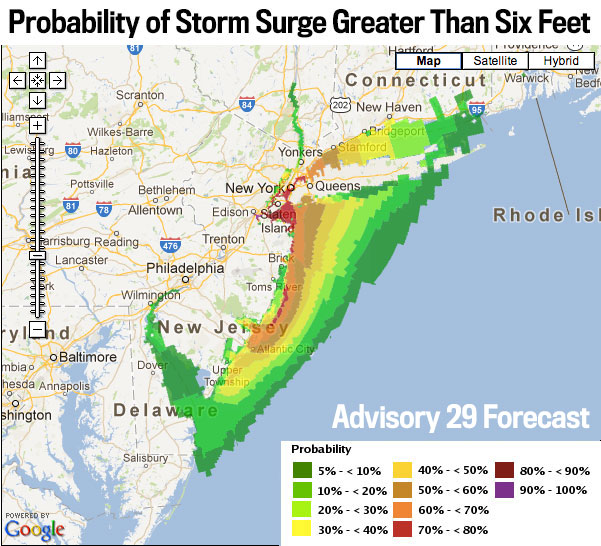

She's huge. She's strong and might get stronger. She's strange. She's directing the might of her storm surge right at New York City.

Update 10/29, 4:49pm: The Eastern seaboard has battened down the hatches. Hurricane Sandy is expected to make landfall in New Jersey in the next few hours, but flooding has been reported in Atlantic City and pieces of New York during this morning's high tide cycle. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority already shut down rail, bus, and subway service in NYC, as did Washington DC's authorities. All eyes are on the 8 o'clock hour, when the storm surge from Sandy will combine with a very high tide to create maximum water levels. In the worst case scenario, the storm surge will hit precisely at the moment the tide peaks at 8:53pm. In that scenario, New York City, in particular, could sustain substantial damage, especially to its transportation infrastructure.

The good news, if there is any, is that the forecast hasn't worsened much. It is what it has been, which is grim. Meteorologist Jeff Masters put it in simple terms. "As the core of Sandy moves ashore, the storm will carry with it a gigantic bulge of water that will raise waters levels to the highest storm tides ever seen in over a century of record keeping, along much of the coastline of New Jersey and New York," Masters wrote today. "The peak danger will be between 7 pm - 10 pm, when storm surge rides in on top of the high tide."

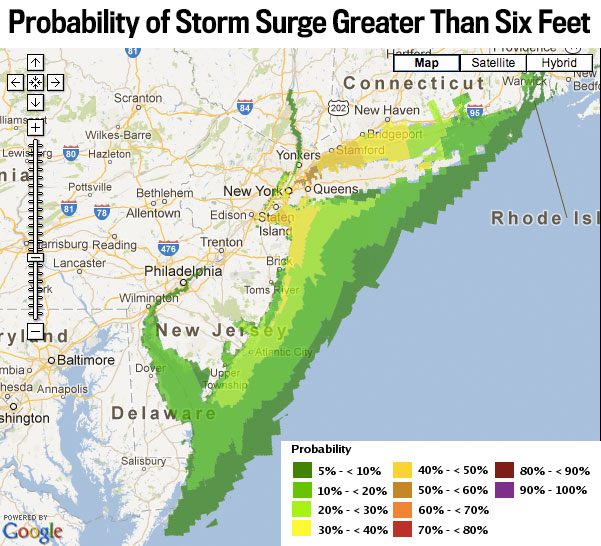

Here's the latest map of the prospective storm surge tonight. You can compare it to the image at the bottom, which shows what the forecast was yesterday.

Hurricane Sandy has already caused her first damage in New York: the subway system will be shut as of 7pm tonight. Meteorologists are scared, so city planners are scared.

For many, the hullabaloo raises memories of Irene, which despite causing $15.6 billion worth of damages in the United States, did not live up to its pre-arrival hype.

By almost all measures, this storm looks like it could be worse: higher winds, a path through a more populated area, worse storm surge, and a greater chance it'll linger. The atmospherics, you might say, all point to this being the worst storm in recent history.

I've been watching weather nerds freak out about a few different graphs over the last several days, which they've sent around like sports fans would tweet a particularly vicious hit in the NFL. You don't want to look, but you also can't help it.

Dr. Ryan Maue, a meteorologist at WeatherBELL, put out this animated GIF of the storm's approach yesterday. "This is unprecedented --absolutely stunning upper-level configuration pinwheeling #Sandy on-shore like ping-pong ball," he tweeted. It shows how cold air to the north and west of the storm spin Sandy into the mid-atlantic coastline. (Nota bene: his models also show very high winds at skyscraper altitudes.)

This morning, the Wall Street Journal's Eric Holthaus (@WSJweather), tweeted the following map. "Oh my.... I have never seen so much purple on this graphic. By far. Never," he said. "Folks, please take this storm seriously." The storm is strong *and* huge. And when it encounters the cold air from the north and west, it will develop renewed strength thanks to that interaction, a process known as "baroclinic enhancement."

"According to the latest storm surge forecast for NYC from NHC, Sandy's storm surge is expected to be several feet higher than Irene's. If the peak surge arrives near Monday evening's high tide at 9 pm EDT, a portion of New York City's subway system could flood, resulting in billions of dollars in damage," Masters concluded. "I give a 50% chance that Sandy's storm surge will end up flooding a portion of the New York City subway system."

Update 1:06pm: To get a taste of how forecasters are feeling, here is The Weather Channel's senior meteorologist, Stu Ostro:

History is being written as an extreme weather event continues to unfold, one which will occupy a place in the annals of weather history as one of the most extraordinary to have affected the United States.

On Twitter, Alan Robinson pointed out that I left out another scary map, the rainfall forecast, which shows the storm "sitting over the Delaware and Susquehanna watersheds." Much of the damage that Irene caused came from flooding rivers. However, there is one key factor militating against similar damage, Jeff Masters of Wunderground says. Irene hit when the ground was already very wet. Sandy is striking when ground moisture is roughly average. Here's Masters whole statement:

Hurricane Irene caused $15.8 billion in damage, most of it from river flooding due to heavy rains. However, the region most heavily impacted by Irene's heavy rains had very wet soils and very high river levels before Irene arrived, due to heavy rains that occurred in the weeks before the hurricane hit. That is not the case for Sandy; soil moisture is near average over most of the mid-Atlantic, and is in the lowest 30th percentile in recorded history over much of Delaware and Southeastern Maryland. One region of possible concern is the Susquehanna River Valley in Eastern Pennsylvania, where soil moisture is in the 70th percentile, and river levels are in the 76th - 90th percentile. This area is currently expected to receive 3 - 6 inches of rain (Figure 4), which is probably not enough to cause catastrophic flooding like occurred for Hurricane Irene. I expect that river flooding from Sandy will cause less than $1 billion in damage.