William Browning | January 15, 2014

Here There Be Alligators

In the rivers and swamps of Mississippi, something huge lurks below the surface

In September, a man named Lee Turner caught something very big in Bayou Pierre, near the Mississippi River. He and three others were in a boat when they spotted it moving slowly across the top of the water. One of them was close enough to toss a treble hook over its back and pull. The hook was seven inches long and attached to a deep-sea fishing line. One of its steel points pierced hard, leathery skin. The moment it did, an alligator vanished into the depths.

Alligators are best hunted at night, when they are most active, and for a while Turner’s hunting party sat in darkness, shining a spotlight along the water, waiting. When it resurfaced, “it sounded like a whale,” Turner said. They turned and saw it, as wide as an office desk, behind the boat.

It stayed up long enough to draw a breath, then went under again and acted as the 17 and a half foot long boat’s pilot as it moved through its underwater world, pulling the four hunters along. It emerged several times to breathe, then would disappear again and tighten the line.

A man holding a rod and reel with a hook embedded in an alligator dictates nothing. He only holds on. These hunters did so for two hours.

The last time the alligator came up its mouth was open and it bit at the boat’s gunwale. One of the hunters picked up a .410 bore shotgun, aimed at the back of the animal’s head and squeezed the trigger. Not long after that, after three other hunters in the area came over to help, the group dragged its dead body onto a sandbar. Turner told me it was then that he knew they had “got a giant.”

It was as long as two men and went on the books at 741.5 pounds, the heaviest caught in Mississippi history.

They loaded it into the boat and traveled the river toward a ramp, where they put the boat on a truck trailer and drove to Canton, Miss.

A biologist with the state’s Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks checked the alligator’s size the following day. It was as long as two men and went on the books at 741.5 pounds, the heaviest caught in Mississippi history.

Alligators are predatory, cannibalistic and efficient hunters. They move deliberately and have armor-like skin. Their jaws are traps. In terms of the food chain, in the swamps and waterways where they live, nothing looks down on them. Occupying a stretch of the country between Texas and the Carolinas and farther south, the reptiles are the same as those that once shared space with dinosaurs more than 150 million years ago. Their brains would fit in a tablespoon, and unless bothered, they are relatively quiet. They can live longer than 50 years.

When I first heard about what Turner caught, my imagination got away from me. I had this haunting vision of it floating in that bayou every night for a half-century, hunting its prey. Sitting in my office cubicle, wearing loafers, this unsettled me.

Not long after that, Dr. Francisco Vilella, a biologist at Mississippi State University, told me alligators typically eat turtles, fish, crabs, birds, beavers and raccoons. Then he added, “Pretty much anything that swims by and they can handle.”

And I pictured a 700-pounder ripping my arm off at the shoulder.

***

Beth Trammell with the 723.5-pound male alligator her party captured. (Photo courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

Beth Trammell with the 723.5-pound male alligator her party captured. (Photo courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

I am from Mississippi. Old rivers bracket the state. The Mississippi runs down the western border, the Tombigbee meanders along the eastern side, and minor rivers and creeks crisscross the middle. Alligators live in almost all of them.

When I was young, our parents let us teenage boys loose in these rivers and creeks. A perfect spot had a sandy bottom and decent current. But if pine straw caked the bottom and the water grew green and stagnant near the bank, no one cared. In the heat of summer, the swimming holes were always cool.

We went to Black Creek, Bogue Homa Creek, Okatoma Creek and the Bouie River. When we got old enough to drive we left our parents behind, but still cut paths to creeks, usually with six-packs of beer. At Shelton Creek, a flat, natural rock surface spread out beside a shaded pool of deep, dark, cool water. This became my favorite spot. The unknown attracts us all and on many Saturdays I caught my breath and let my hands use the rock to push me farther and farther down into the water. I wanted to reach the bottom, to feel what was deep and untouched, but can’t recall ever making it. No one worried about alligators.

Today, I live beside the Tombigbee in the northeast corner of the state, where there are fewer alligators than in the southern end. Still, a game warden told me if someone went on the Tombigbee near my home at night with a flashlight, it would be nothing to find 50 or 60 pairs of alligator eyes glowing back. Fishermen see them all the time.

I am not much of a fisherman. But the closest I have ever come to a wild alligator, as far as I know, was one day in the mid-1990s when my father and I put his boat into Lake Columbia, in southwest Mississippi, and went fishing for bass. We started at daybreak. By midday we had no luck and decided to try the lake’s far side, where a forest met the water’s edge and where we had seen no one fishing that day.

While coming toward a cut of land that jutted out into the water, I saw what looked like an old, black garbage bag on the shoreline. The sun shone off of it in a dull way that made me think it had been there a while. It looked wet and had odd angles, like it was twisted. About the time I shut the motor off and we began coasting, I realized it was not a bag but an alligator, probably 8 feet long and as wide as a car tire in the middle. We were heading straight toward it.

it came over me that there was something powerful and out of our control in the water and my blood pressure rose.

For a few moments that alligator sat stone-still as our boat moved silently through the water. It was sunning itself. We got close enough to see that its eyes were open. Then, without warning, it moved with a frog’s sudden grace, running itself off the shoreline into the water in front of the boat and disappearing. There was hardly a splash. I was mesmerized.

My father was not. He said over his shoulder, “Go.” When I did not, his voice grew more direct and forceful, and he said, “Get us out of here. It wouldn’t be nothing for that thing to turn this boat over.” With that, it came over me that there was something powerful and out of our control in the water and my blood pressure rose. Tasting fear, I cranked the motor and we left. I did not look back, but my thoughts were where it had gone, under the water.

Somewhere, that alligator was gliding away. I was sure its eyes were looking up.

Turner caught his alligator in south Mississippi. Because it was the fifth record-setting catch during Mississippi’s 10-day annual alligator season, and because of the menacing place alligators hold in our minds, the news spread far and fast. Media outlets around the world ran stories with pictures. The words “monster” and “beast” were in the headlines. Australia and Canada called. England and China called. The world knew of the vast Mississippi River, but had never considered the enormous gators that lived under its surface.

In the middle of the ruckus, Ricky Flynt, an alligator expert with the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks, spoke on camera with a TV station. He is an earnest man, with a serious manner, and toward the end of his interview, while footage of Turner’s alligator rolled, he said, “I believe we’ve got alligators in Mississippi in the 900- to 1,000-pound range. Whether an alligator hunter can be successful in getting them in … is another story.”

It sounded like a challenge, but a warning, too.

***

Hunting Regulations

Persons eligible: Only residents of the State of Mississippi who are sixteen (16) years of age or older may apply for an Alligator Possession Permit. Non-residents may participate as alligator hunting assistants.

Bag limit: Each person receiving an Alligator Possession Permit will be allowed to harvest two (2) alligators four (4) feet in length or longer, only one (1) of which may exceed seven (7) feet in length.

Capture and Dispatch Methods:

a. Use of bait or baited hooks is prohibited.

b. Alligators must be captured alive prior to shooting or otherwise dispatching the animal. It is unlawful to kill an unrestrained alligator.

c. Restrained is defined as an alligator that has a noose or snare secured around the neck or leg in a manner that the alligator is controlled.

d. Capture methods are restricted to hand-held snares, snatch hooks, harpoons, and bowfishing equipment.

e. The use of fishing lures or other devices (with hooks attached) for the purpose of catching alligators in the mouth is prohibited.

f. All alligators must be dispatched or released immediately after capture and prior to being transported.

g. Any alligator that is captured with a harpoon or bowfishing equipment must be reduced to the bag and may not be released.

h. Firearms used for dispatching an alligator are restricted to long-barreled, shoulder-fired shotguns with shot size no larger than No. 6 and bangsticks chambered in .38 caliber or larger. No pistols are allowed.

i. All shotguns and bangsticks must be cased and unloaded at all times until a restraining line has been attached to the alligator.

j. No other firearm or ammunition may be in possession of the permittee or hunting party.

Catching an alligator

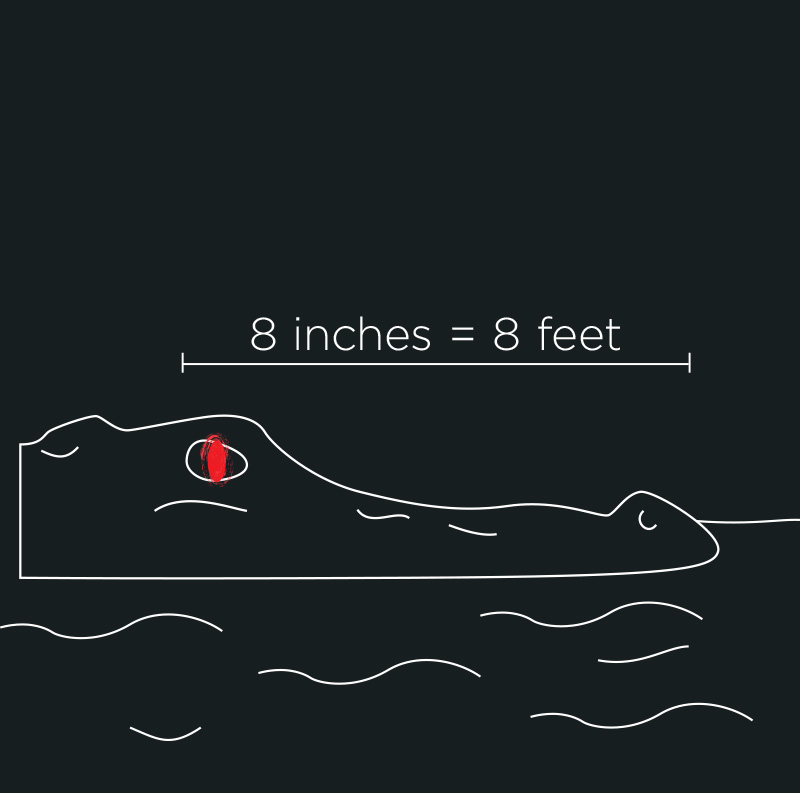

Estimate its length

The snout length (the distance between the nostrils and the front of the eyes) in inches can be translated into feet to estimate the total body length.

Capture it

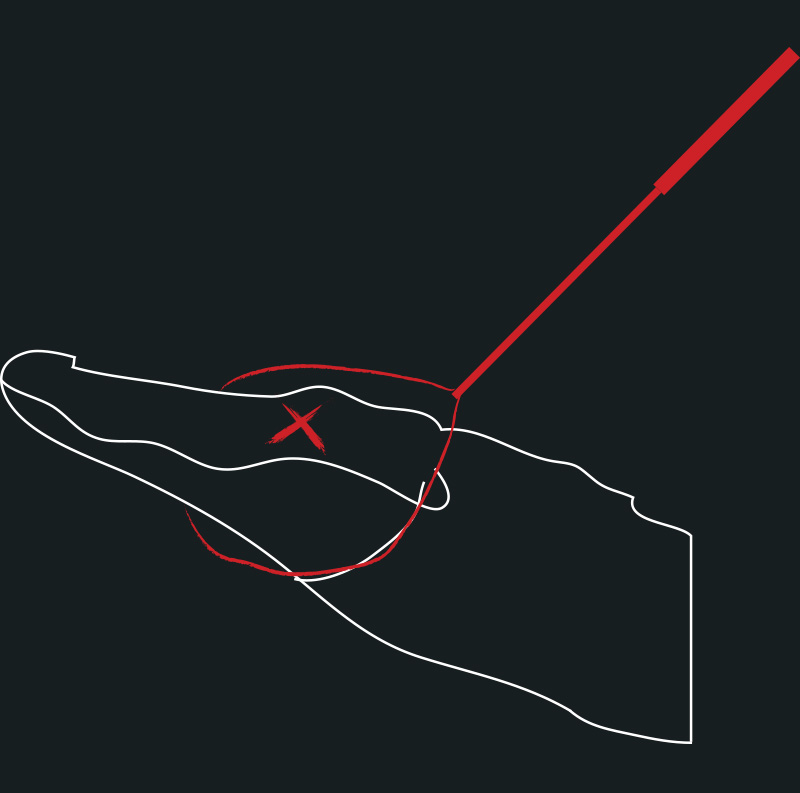

The use of bait and hook is illegal. Legal methods: Snatch Hooks (hand thrown or rod/reel), Harpoon (with attached line and/or buoy), Snare (hand or pole type), Bowfishing equipment (with attached line and/or buoy).

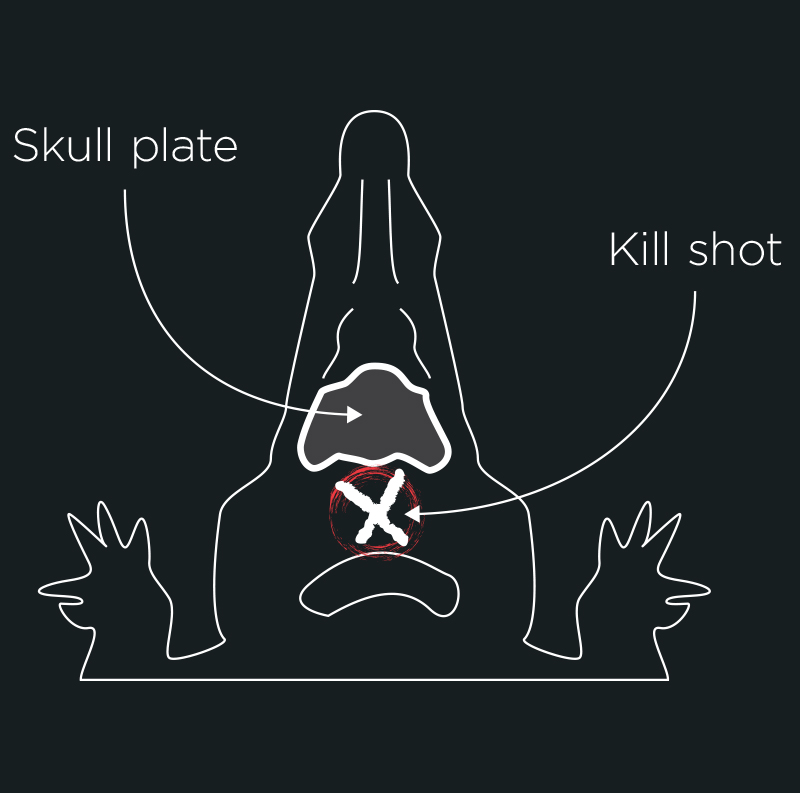

Dispatch it

Use a shotgun or bangstick once the alligator is restrained and controlled with a snare. To safely and humanely dispatch the alligator, aim for the center of the spine directly behind the skull plate.

As long as people and alligators have shared Mississippi, there have been people who hunted the creatures. Spanish explorers called them el lagarto, which means “the lizard,” and that morphed into what we call them today.

The Choctaw believed an alligator told the creator the best water was where cypress trees grew in bayous, so the creator placed the alligator there. Native Americans saw them as mysterious, respected hunters. In a northern Mississippi plain in the 1930s, an archaeologist was poking around a native burial ground when he found the remains of a human skeleton covered with turtle shells. On top of it all was an alligator skull.

In the late 1960s, because of illegal hunting, they were an endangered species. In an effort to replenish their numbers, and to help control the beaver population, Mississippi wildlife officials drove horse trailers loaded with 3,500 baby alligators from Louisiana to the Mississippi State Fairgrounds.

The babies were handed out in bags to landowners, who took them across the state and released them into the waters.

It worked.

By the late 1980s, they were no longer endangered. The last census, in 2000, suggested there were roughly 48,000 in the state’s fresh water. That was a conservative estimate, Flynt said, and it is safe to assume there are even more today. They are prevalent enough that the state legislature gave the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks the specific authority to deal with alligators. Flynt says the agency gets 300 to 500 phone calls a year.

since 2005, the state has allowed its residents a few days each year to kill them.

The program mainly handles what it calls “nuisance” alligators, which for the most part are young alligators that sometimes wander into backyard swimming pools or neighborhood ditches. Still, they routinely attack dogs and other pets that roam near water because of their resemblance to their natural prey.

“Yes, a gator will grab a dog if one ends up in their dining room,” a wildlife official said.

For most of the year, it is still illegal to possess or hunt alligator. But since 2005, the state has allowed its residents a few days each year to kill them.

Almost everyone in Mississippi is a hunter of some sort, and the alligator hunts are open to the public. There are a limited number of permits given out via an application process and far more people apply than receive them. It is not uncommon for applicants to wait several years between hunts. The men and women randomly chosen fan out across the state in groups because one person, acting alone, cannot catch an alligator. At least not a big one. It is an exhausting, exacting endeavor.

For safety and sporting reasons, you are not allowed to shoot them until you have secured a part of an alligator’s body with a snare, a loop of wire attached to a pole. To get a snare attached, you have to be within a few feet of the alligator, and to get close, most hunters begin with a rod and reel and treble hook.

“It’s more alligator fishing than alligator hunting,” Flynt said.

Hunters like Lee Turner and his friends gather on boats and go out at night looking to spot the gators floating in the water, waiting for their next meal. Midnight hunts are the norm. When a spotlight reveals a set of glowing eyes, a hunter casts a hook over the body, jerks it into the skin and holds on. An alligator can stay beneath the water for an hour. After they go under, you let them wear themselves out. Perhaps you try to get another hook or two set. This can last hours.

When they tire and raise to the surface, you slip on the snare. This is tricky. Alligators are surprisingly quick. Hands have been chewed up.

Once a snare is on, you are allowed to shoot them with a shotgun loaded with birdshot. A biologist, describing an alligator’s toughness, said they are built with “bullet-proof bone and skin.” But at the base of their skulls there is a soft spot of tissue, their lone weak spot, and the place to take aim at point-blank range. Then comes the part that typically takes the longest: getting the massive body, all dead weight, loaded into a boat.

they are built with “bullet-proof bone and skin.”

Because so many steps are involved, many things can go wrong, and usually do. This often begins early in the process, when an alligator that is hooked tries to escape, and the splashing and cheering and maneuvering begins. Flynt calls this a “Chinese water dance.” A prehistoric thing weighing several hundred pounds fighting for its life can be messy. Add into this several adrenaline-filled hunters gathered in a small boat, a loaded gun, several different fishing lines, the absence of sunlight, and drinking (which is illegal but known to occur), and things rarely go as planned.

“It is truly an adventure,” Flynt said. “There is an element of danger involved. It can be very dangerous.”

That is part of the appeal. The hunters who apply for tags are not professionals or wildlife experts, like Steve Irwin, the late Australian known as “The Crocodile Hunter” for catching the alligators’ more aggressive, saltwater-tolerant cousin. They are mostly just middle-class Mississippi natives who grew up beating around the outdoors, hunting deer, quail and ducks. Though alligator meat can be battered and fried, it is tough and hardly worth the fight. That’s not why people hunt them.

It is a pursuit undertaken mainly for the novelty and thrill. One hunter said, “It’s not like a deer is going to jump in the stand and bite you.”

During the season, Ben Mask, who is 32 and works for Tupelo, Miss., Light and Water, caught an alligator in Tibbee Creek in northeast Mississippi.

“They can hurt you,” he said. “That makes it fun.”

Mask’s alligator weighed 620 pounds. Big, but no record. Usually, a single shot to the soft spot is enough to kill. The one Mask caught proved resilient, though, and it took two shots. His hunting party then shot it a third time, as well. I asked why.

“Insurance,” he said.

***

Dustin Bockman's hunting party with their 727-pound catch. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

Dustin Bockman's hunting party with their 727-pound catch. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

The 2013 hunt began at noon on Aug. 30 and ended at noon on Sept. 9. Approximately 920 hunters received permits and more than 2,600 people went out searching for alligators. Exactly 671 were killed. Every single record the state keeps track of was broken.

Exactly 671 were killed. Every single record the state keeps track of was broken.

The first one fell early.

On the opening night, Brandon Maskew, a 27-year-old who goes by “Boo” and works for a trucking company in Laurel, Miss., took his three-person party onto the Pascagoula River. It runs through the state’s southeastern corner for about 80 miles before emptying into the Gulf of Mexico.

In a marsh not far from the Gulf, Maskew came across a gator and hooked into it. The “process” went well and only took about 40 minutes. When it was over, the party had caught a female alligator that was 10 feet long and weighed 295.3 pounds — both records for the gender.

The next morning, Maskew and Allen “Big Al” Purvis, who went on the hunt, took a picture standing beside the alligator. It hung, suspended in the air, by industrial-strength straps attached to a front-end loader.

In that photograph, Purvis has on a “Tequila Sunrise” T-shirt and Maskew, in cut-off cargo pants, has his right arm locked around Purvis’ neck. They are all smiles.

The tone of the next nine days had been set.

Lee Turner stands next to his record-setting 741.5-pound gator. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

Lee Turner stands next to his record-setting 741.5-pound gator. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

That weekend, shortly after midnight on Sept. 1, Beth Trammell, a first-time hunter from Madison, Miss., was hunting in the Yazoo Diversion Canal in Issaquena County. This is the state’s eastern edge, part of the Mississippi Delta. Trammell’s party landed a 723.5-pound male alligator.

It broke the state’s previous size-record for a male by more than 25 pounds. But it only stood for an hour and a half.

While Trammell’s hunting party was pulling their alligator in, a 27-year-old UPS driver named Dustin Bockman was a few miles south hunting the Big Black River in Claiborne County. Bockman, a bachelor, is a native from Vicksburg and went hunting in shorts and a T-shirt — you do not need camouflage to hunt gators.

This was not his first time. “Anything you can kill, I’ve killed it,” he told me.

Bockman’s brother and best friend went into the Big Black River with him. They chose that river because they fish there regularly and always see alligators.

Alligators move across the surface with their eyes and top half of their snouts, and maybe a third of their body, showing above the water. As they swim — their powerful tails and feet propeling them along — it is hard to judge their size.

“We had no idea they were as big as they are,” Bockman said. Alligators you see are usually small, like the one Bockman caught as a child. He grew up near the Big Black River and one day, when he was kid, he spotted a 5-foot long alligator walking a neighborhood road and he caught it. The local paper took his picture.

Although most hunters use a rod and reel to snag a gator, Bockman took a different approach. He dropped a handful of glow sticks, the kind people wave at concerts, into an empty 3-liter water jug, and he tied the jug to a rope attached to an arrow in a crossbow. The plan was to shoot an alligator with the arrow and, after it went under, trail the light of the glow sticks along the Big Black River.

They rode the river for an hour. Bockman said in that time, shining a spotlight around, they saw hundreds of eyes on the water. Most disappeared as soon as the light found them and the boat crept along, powered by a quiet trolling motor.

They turned into a slough and hunted a swampy area. But they didn’t spot “a big one,” Bockman said, so they turned back toward the river. As they approached the river, they passed one that held their attention. It was floating, and Bockman pulled the boat along behind it, and followed. He wanted to be within 10 feet before pulling the crossbow’s trigger.

It took hours to get that close. Bockman described it as a game of cat and mouse. He remembers that when the boat got close enough he said, “Oh my God.” When he shot — the arrow lodged behind its left shoulder — the alligator went under and began pulling the boat along, upstream, and then downstream, and then back again, slowly. Every now and then it dropped to the bottom and sat still. Each time the boat stopped, the crew’s excitement grew.

After several hours, the alligator grew tired and surfaced long enough for Bockman to get the boat beside it. They got a snare on it, but it kept wanting to slip off and Bockman, fearing the gator would be lost, picked up his brother’s .16-gauge shotgun. He stuck the barrel into the water and fired a shot toward the alligator’s soft spot. When he did, water flew high in the air and the pressure peeled the barrel back.

“I looked like Elmer Fudd,” Bockman said.

Lee Turner with his 741.5-pounder. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

Lee Turner with his 741.5-pounder. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

He shot again. The second shot killed the reptile. Then the work began.

The three men wrapped their arms around the animal’s leathery skin and pushed and pulled and tugged for four hours, trying to get the body out of the water and onto a sandbar. Somehow, they needed to get it in their boat, but couldn’t lift it alone, and if they left it on the bank, who knew what might happen. So, as the mosquitoes bit them, they waited. By the time some other hunters happened by and helped them get it loaded in the boat, Bockman’s party had been on the water for 12 hours.

Flynt met them to inspect the gator. It weighed 727 pounds and set the new record for a male alligator caught in the state.

It stood for six days.

Lee Turner broke it. He is a 30-year-old resident of Madison, a suburb of Jackson. He works for a shipping company and is married with a 1-year-old child. He is tall with a big smile.

He grew up in Quitman, in east Mississippi, near the Chickasawhay River and his father was in the oil business. They had a farm. “I’ve been hunting ever since I was old enough to go with my dad,” Turner said. There were alligators in the reservoir near where he grew up. They ignored them while waterskiing.

“They don’t really bother you,” he said. “They kind of stay in the shadows.”

Turner took John and Jennifer Ratcliff, experienced gator hunters, and Jimmy Greer, a friend, on his hunt. At 9 p.m. on Sept. 7, they put a boat into the Mississippi River at a public ramp near Port Gibson. They had two spotlights, four deep-sea fishing lines, a couple of snares and a .410-bore shotgun.

“I was hoping to catch a 10-foot gator,” Turner told me. “That would have been great.”

They spotted an alligator immediately. It was gliding around near the ramp and about 5 feet long. Turner went after it — it was his first time, his eyes were wide — but it got away, and they headed up river.

Alligator hunters who receive tags actually get two. One is for an alligator shorter than 7 feet; one is for one longer than 7 feet. Not long after heading north, Turner’s party caught an alligator that was 7 feet 3 inches long. The process took about a half-hour –— “It didn’t put up too much of a fight,” Turner said. They got it into the boat, secured its jaws shut with Duct tape, and took some pictures. But they wanted a big one. So they released it and continued up river.

Three hours in, they had spotted about 30 alligators, but none big enough to chase. They turned into Bayou Pierre, a small tributary of the Mississippi River known for its warm water. When they did, they spotted two near the bank, and they looked big, but Turner kept moving.

Eventually they caught a “runt,” Turner said, that was 6 feet 10 inches long. It took only 20 minutes to get in. That took care of one tag.

They wanted to go deeper into the bayou but saw lights up ahead bouncing around on the water. Not wanting to disturb another hunting party, they turned back toward the Mississippi. Near the river, they spotted the two big ones they had seen earlier. One turned to get farther into the bayou. The other headed for the river.

Turner followed.

As they inched closer and closer, the alligator, sliding along the surface with a spotlight lighting its back, appeared bigger and bigger. Turner said at one point he turned toward John Ratcliff and said, “That’s a big gator.”

Ratcliff, who seven years ago held the record for the biggest alligator, responded, “Ain’t but one way to find out.” Then he took a rod and reel and threw a line. The alligator, hooked, went under. It stayed down for about 10 minutes before surfacing behind the boat.

“We heard it before we saw it,” Turner said.

After the group laid eyes on the animal up close, and were confronted with the size of what they were attached to, Ratcliff spoke first. He said they needed a plan.

“No matter how prepared you are,” Turner said, “when you get one on the line everything goes haywire. It always crumbles.”

“No matter how prepared you are, when you get one on the line everything goes haywire. It always crumbles.”

The party managed to get three more lines hooked into it. Because of its massive size, the gator broke three. Turner held the last one. He had to lean back to offset the force, like battling a tuna at sea, as the animal pulled the boat along.

Eventually, it went to the bottom in water about 12 feet deep. It had been two hours since Ratcliff got the first hook in and the group, after securing three more hooks into the animal’s side, waited.

When it finally came up again, it was agitated and that is when it began biting at the fiberglass boat. Turner said they did not feel like it was trying to attack them, but was just panicked, confused and scared. Still, Ratcliff, sensing urgency, said it needed to be shot, and soon.

Ratcliff was near the edge of the boat trying to work his nerve up to slip on the snare. His wife was holding a spotlight. Turner was holding the line. So Greer picked up the shotgun and walked to the edge, beside Ratcliff, who jerked a snare down around the animal’s head. Greer leaned out over the water with the alligator beneath him, aimed at the exhausted animal, pulled the trigger.

It only took one.

When alligators die they lose buoyancy, and Turner said the moment the shot rang out the rods with lines attached to it each “fell into a U shape” as the alligator sunk to the bottom.

After the four of them got it pulled halfway onto a sandbar, the Ratcliffs took the boat down the river looking for help. Turner and Greer sat with their catch. It was about 2 a.m.

Three other hunters helped get it loaded into the Turner party’s boat and they drove back to Port Gibson. With the alligator riding in the boat, they went to Canton, a middle Mississippi town near where Turner works. A friend of his who owns a backhoe met them there and helped lift the alligator into the back of a pickup.

They went to a weigh station off of Interstate 55 to see how much it weighed. By then, the sun had risen and as they waited to get on the scales, about 50 people who happened to be passing by stopped to stand beside the gator in the truck bed, and they all took pictures. It cost Turner $10 to weigh it.

Flynt came and made the 741.5-pound weight official. By the time Turner crawled into bed that night he had been up nearly 48 hours.

That same day a 33-year-old banker named Ben Walker caught an alligator in the Yazoo River, a Delta waterway that runs from Greenwood to Vicksburg. It was not as heavy as Turner’s, but at 13 feet 7 inches, was the longest in state history. To get it out of their boat they used a truck wench and stored it in a walk-in freezer until Flynt could verify the record.

Walker plans on getting the alligator’s head mounted — it will cost about $1,000 — and hanging it at his father’s cabin beside the Yazoo River. It is fitting place, he said. He feels sure the animal “left a footprint” in the area, eating pigs and deer.

Bockman, who told me people on his UPS route call him “gator man” now, is having a pair of boots and a new wallet made from his alligator’s hide. He also wants to mount the head. He will get a piece of driftwood from the Mississippi River and fix the head to it, along with the broken barrel of the shotgun that killed it, and the empty water jug.

Turner sent his alligator to Florida with a trapper he met through the Ratcliffs. He is going to use the money he gets for its hide to have the head mounted. He isn’t sure where it will go, though, because his wife doesn’t want it inside their home. That is OK with Turner. He already has a deer head, a turkey and two squirrels on the wall.

There just isn’t room for an alligator.

***

Ben Walker and his group with their 13'7" alligator, the longest in state history. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

Ben Walker and his group with their 13'7" alligator, the longest in state history. (Courtesy of Ricky Flynt)

I asked the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks how many unprovoked alligator attacks have occurred in the state. Florida has attacks occasionally, and there have been fatalities there, though rarely.

Mississippi officials told me no such attacks have ever been reported. This struck me as odd.

Then I remembered something Walker said. Before becoming a banker, he was a wildlife biologist.

“They’re going to stay away from us as much as possible. They associate humans with danger.”

“You’re not going to step on an alligator the way you might step on a water moccasin,” he said. “They’re going to stay away from us as much as possible. They associate humans with danger.”

In that way, we’re a lot like gators, because we associate danger with them.

Near where I grew up, beside an old two-lane highway going just outside a south Mississippi community called Brooklyn, someone once kept an alligator chained up in front of their home.

It was a rural oddity, something that made everyone shift to one side of the car when you drove past in the hope that it would be there, sitting still, like frozen from another time. Most often, though, it wouldn’t be. That chain was long and on a pulley system, and there was a pond nearby, and that alligator stayed out of sight a lot. It mostly lived in the imagination.

A few weeks ago, I learned the man who chained that alligator was named Carnes Archer and I wanted to understand why he kept a gator. When I learned Archer died several years ago, I was referred to John Dearman, a friend of the family who lives in the area.

This is what he told me:

One day in August of 1957, Archer caught an alligator in the water not far from where the Black Creek meets Red Creek. It was a female about 7 feet long. Archer brought it home and chained it up, where it became something of a local attraction. Archer fed it road kill.

Over the years it grew to be 14 feet long. Had it been one of the alligators caught in the wild and killed this season, it would have been a record.

When people stopped to stare, Archer would ham it up with his pet, which everyone called “Chomper.” He would rattle the chain, and when the alligator lurched near him, thinking it was going to be fed, Archer would lay down beside it and pretend to take a nap.

“He was the only person who could do that,” Dearman said.

I asked Ricky Flynt about “Chomper” recently. He said the state was aware of the situation, and after receiving a handful of complaints, wildlife officials investigated. In 2009, after Archer had passed away, the state asked Archer’s son for paperwork that could document how the alligator came to be chained up in his father’s front yard in Brooklyn.

After that, Flynt said the alligator suddenly “came up missing.”

I called Archer’s son to ask him about that, but he didn’t call me back. Brooklyn is the kind of place where people keep their secrets and do not appreciate journalists poking around with questions. No one knows where the alligator went, if anywhere.

According to Dearman, it died in 2011. He says the family did not have its head mounted, but instead buried it on Archer’s property.

At least that’s what he said.

All I know is, the next time I find myself passing through, I plan on slowing down, leaning over in my truck and taking a good, hard look, just to be sure.