On Monday night, Utah’s governor signed into law a bill that makes Utah the only state in the union to allow the firing squad as a method of executing condemned inmates.

One other state, Oklahoma, allows for death by firing squad but only if the lethal injection process is ruled unconstitutional by a court.

Why the firing squad?

Since 2011, the Europe-based manufacturers of the most common execution drugs have refused to sell them to American prisons. They flat-out disagree with the practice, and hope that cutting off the source of the drugs will eventually lead the US to stop executing people.

The Guardian’s Ed Pilkington reported on the boycott at the time: “Though the new restricted list covers the only two drugs currently used in American death penalties, the fear is that intrepid states will find a way round the controls by using other sedatives not on the list.”

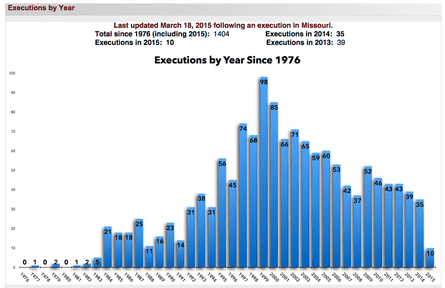

And he was right. Since the ban, some states have simply stopped executing people, and by 2013 the number of executions in the US hit its lowest point since 1994. Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, New Mexico, Maryland and New York have all passed legislation to end the practice in the last decade. Pennsylvania’s governor instituted a moratorium in February to investigate the state’s capital punishment system.

That leaves the handful of states that still execute people – largely Florida, Texas, Missouri, Georgia and Oklahoma – struggling with a dwindling supply of drugs and turning toward other methods. They have most often chosen compounding pharmacies, companies that cook up made-to-order cocktails that resemble the drugs they used to get from the European companies. And they have done so secretly, as states pass laws to protect the makers of the drugs from public disclosure. (The Guardian has sued in several of those states.)

Or, they do what Utah did on Monday, and take another route entirely. “We would love to get the lethal injection worked out so we can continue with that but if not, now we have a backup plan,” Utah state representative Paul told the Associated Press.

But the firing squad?

Though it may seem a relic from the distant past, it was only 10 years ago that the state actually did away with the shooting people to death. Inmates sentenced before 2004 were given the option to choose the firing squad over lethal injection, which is how in 2010 Ronnie Lee Gardner became the last person executed in the US by firing squad.

Ray first proposed the firing squad bill last May, a month after Oklahoma’s botched execution of Clayton Lockett.

“It sounds like the wild west, but it’s probably the most humane way to kill somebody,” Ray said.

Is it more humane?

Ronnie Lee Gardner’s brother, Randy, says no. “There’s no humane way to execute anyone,” Randy Gardner told NBC news on Monday. “I had the opportunity to see my brother after four bullets hit his chest, and I could have put my hand in anyone of the holes. It didn’t look very humane to me.”

“He was tied down with a hood over his head. Terrorists around the world and Isis, when they execute people, that’s what they do.”

Last year, Ed Pilkington spoke with Deborah Denno, a Fordham University professor who specialises in execution methods:

Denno has studied the history of the firing squad in the US, and found that in most of the cases in which it was used it was relatively quick and effective. In 1938, a “human experimentation” was carried out on a 42-year-old inmate who was executed by firing squad, with his heart monitored using electrocardiograph tracing. The results showed that his heart was electrically “silent” within a matter of 20 seconds.

The only known case of a botched execution by firing squad, in 1951 in Utah, appears to have been an act of vengeance on the part of five trained marksmen pulling the trigger. They targeted the wrong side of the prisoner’s chest, apparently intentionally, and he bled to death.

Are there other options?

Tennessee, which last executed someone in 2009, is considering bringing back the electric chair, though its death row inmates have sued.

Oklahoma, too, is looking to the electric chair, which it is only allowed to use if lethal injection is found unconstitutional. Last year, after Clayton Lockett’s botched execution, the corrections department and a history museum were in disagreement over who, exactly, owned Old Sparky.

Oklahoma also joins Missouri in exploring the return of the gas chamber, which has a rather gruesome track record of its own. A 1992 New York Times article recounted the death of Eugene Harding as he lay there “gasping, shuddering and desperately making obscene gestures with both strapped-down hands”, a death so drawn out it led Arizona to switch from the gas chamber to lethal injection.

Compare that with the scene in Arizona last summer, when Joseph Wood took one hour and 58 minutes to die by lethal injection. “I saw a man who was supposed to be dead, coughing – or choking, possibly even gasping for air,” wrote one witness.

A top American judge has recently called the decision to move from traditional methods such as the firing squad, electric chair, gas chamber and hanging to lethal injection a mistake. “Subverting medicines meant to heal the human body to the opposite purpose was an enterprise doomed to failure,” Alex Kozinski wrote.

Why don’t we just stop executing people?

Ending the death penalty would be the easiest way to solve the problem, yes. And several states have enacted de facto moratoria in the last few years.

Public support for the death penalty was at its highest in the late 1990s, when 80% of Americans said they favoured the execution of convicted murderers. (That’s also when actual executions neared their highest.)

By 2013, support had declined to about 60% in Gallup’s annual survey, and the results remained unchanged last year, even after three lengthy botched executions made headlines.

What happens now?

In Utah, there are currently eight prisoners on death row, but no executions scheduled for the next two years. So while the governor made headlines for signing the law on Monday, it won’t actually be putting anyone in front of that new firing squad for a while.

All eyes are currently on the US supreme court, which in April will hear a lethal injection challenge brought by four death row inmates in Oklahoma, one of whom has already been executed. The inmates are challenging the use of a sedative called midazolam, which was used in all three of last year’s botched executions.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor has said she is “deeply troubled” by the botched midazolam executions. “It is true that we give deference to the district courts. But at some point we must question their findings of fact, unless we are to abdicate our role of ensuring that no clear error has been committed,” she wrote, a week before the court agreed to hear what amounts to the most high-profile challenge to American executions in decades.

If they rule against the continued use of midazolam, it’s likely Utah won’t be the last state to revisit the use of the firing squad.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion