The Rockies unfurled outside Kristen Yeckley’s passenger window, but she kept her eyes on the speedometer.

No more than 5 mph over the limit, she urged her mother. Hands at 10 and 2.

She had stayed up past 3 a.m., sobbing, praying, plotting the route back to Pinellas Park. The drive meant committing a federal crime with her 5-year-old son in the backseat.

Kristen kept imagining handcuffs, the fear on Tyler’s trusting face. If they were pulled over, she would use his medical records to plead for sympathy.

She and her husband, Joe, had saved up for their dream home with a backyard pool. They had comfortable jobs, poker nights, a college fund in their son’s name.

Then came Tyler’s diagnosis.

When doctors said he was out of options, Kristen and Joe vowed to do anything, even split up their family, to give Tyler a chance with a treatment Florida doesn’t allow.

That brought Kristen here, to the sloping road out of Colorado last summer, 2,000 miles from home — with vials of liquid medical marijuana buried in her mother’s suitcase.

♦

Worry first tugged at Kristen in the line to see Santa Claus.

“Do you think Tyler has a lazy eye?” her best friend had asked earlier that week in 2014. Kristen, then 30, said Tyler was just being a 4-year-old, making funny faces.

At Tyrone Square Mall in St. Petersburg, Santa reached for Tyler in his argyle vest.

Kristen saw it. Something was wrong.

“Okay, Ty, look here, look here,” she called out, hoping his right eye would straighten.

But it stuck, turned inward. The left squinted. His mouth scrunched into a half-smile.

The day after Christmas, Joe, then 33, took Tyler to an eye doctor.

“I thought he was cross-eyed,” Joe said. “It seemed to make sense.”

Hours later, an MRI revealed something far more worrisome. A lesion on Tyler’s brainstem.

♦

Tyler had arrived on Super Bowl Sunday in 2010, soft with peach fuzz. Kristen and Joe watched the game from the hospital bed. As the winning quarterback lifted his blond-haired boy to the sky, Joe did the same, eyes welling.

Kristen and Joe met in their mid-20s. She taught elementary school. He worked in finance.

They married on Sunset Beach and bought their house two years later, on a woodsy lot with a tangerine tree. As they tore off wallpaper, 2-year-old Tyler played hide-and-seek in the cabinets.

Pictures of him filled their phones: blue-eyed Tyler picking daisies for girls at school; Tyler a statue in a sea of wiggly kids, mouthing the syllables on the vowel chart. He built train sets, dreamed of driving the Disney monorail, the horn playing When You Wish Upon a Star.

“I’ve got a great idea,” he would tell his parents, before launching into a negotiation to sleep in their bed.

In mid-January of 2015, the family returned to Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital for another MRI.

Doctors now called the lesion a tumor. It was growing, fast, and they needed to operate.

♦

Tyler hadn’t yet started kindergarten or lost a tooth. He taught the days of the week to the stuffed animals piled on his bed.

Doctors avoided the word “terminal,” but the message was clear: Don’t waste the time you have left searching for solutions.

Kristen had wanted him to grow up with friends who were like siblings. Most weekends, their home became the gathering place for a tight-knit group of couples and their kids, Tyler’s closest friends.

At the end of January, not long before Tyler’s fifth birthday, the Yeckleys rallied them for a “bravery party.” As his friends painted, Tyler’s parents sat him on their bed.

“Tomorrow is probably going to be a bigger doctor’s appointment,” Kristen explained. “They’re going to try to fix your eye.”

She and Joe worried Tyler would emerge from surgery mute, paralyzed or tethered to a feeding tube, as the doctors had warned was possible. Tyler, upset he might miss a friend’s birthday party, started to cry.

Sullen, he joined the other kids and smeared a blob of blue paint on his paper.

“A monster,” he grunted, but then added a wobbly red smile.

Tyler awoke the day after surgery, hungry for mac and cheese. Surgeons had cut away about 30 percent of the tumor, but the rest reached like tentacles into his brain. They called it an anaplastic astrocytoma, a rare, aggressive cancer.

Doctors avoided the word “terminal,” but the message was clear: Don’t waste the time you have left searching for solutions.

“Stay off the computer,” Kristen recalled one doctor telling her, “And take your son to a park.”

♦

Kristen stopped teaching. Joe would keep them afloat financially.

They had always balanced each other. Kristen’s spontaneity and raspy laugh complemented Joe’s analytical, level-headed way. They were like a canoe, Kristen joked. Joe kept them powering forward, “and I am totally the direction.”

That winter, Joe called name-brand hospitals for second opinions. Radiation therapy would hold the tumor’s growth in check for a few months, but then what?

Tyler was at an age Joe had long looked forward to. He envisioned tee-ball games, Tyler dribbling down the soccer field. He had feared becoming a father, but now it was life without Tyler that was terrifying.

Tyler watched as Kristen disappeared into her bedroom for hours at a time.

“Why is Mommy crying?” he would ask.

“Without Tyler, my husband will never love me,” Kristen said to herself. “He’s just going to look at me and see Tyler, so how could he love me after this?”

♦

The idea surfaced one poker night.

As the Yeckleys’ friends fumbled over what to say, one mentioned reading about cannabis killing cancer.

Kristen began printing articles, highlighting line after line.

Lab studies showed promise. Marijuana’s chemical compounds had been shown to kill cancer cells in mice and rats, while protecting normal cells. Kristen noted two chemicals in particular: tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, responsible for the drug’s high; and cannabidiol, or CBD, which lacks psychoactive side effects.

One study said combining THC and CBD could make radiation therapy in human brain-cancer cells more effective.

But Kristen kept running into the same dead end. The federal government lumps marijuana with some of the most dangerous street drugs, making rigorous study prohibitive. It had never been seriously tested as a cancer treatment in U.S. patients.

She needed to see what it was like in Denver. She needed to know they had tried everything.

“There’s not a lot of evidence that it works, right?” said Dr. Peter Forsyth, chair of neuro-oncology at Moffitt Cancer Center. “But the more accurate statement is it just hasn’t been investigated thoroughly and properly to make a decision about whether it works or not.”

And it wasn’t available in Florida, where voters had rejected a push for medical marijuana in 2014. A law granting some patients access to a low-THC strain of marijuana, nicknamed Charlotte’s Web, had been tied up in Tallahassee. It wouldn’t become available for two years.

Meanwhile, Kristen read about Colorado, where voters had approved medical marijuana in 2000. Desperate families like hers were gathering there, calling themselves “refugees.”

She and Joe supported marijuana legalization. Kristen’s own father smoked it to ease muscle pain caused by multiple sclerosis.

Looking at the paltry research, Joe hesitated. This was their son.

He asked the doctors he had been calling if they would warn against using it.

“I just need to know one thing,” Joe asked. “Would it hurt him?”

One by one, they told him, “No.”

♦

Weeks after surgery, as Kristen prayed to see Tyler’s smile again, she devoured stories of impossible recoveries made possible by medical marijuana.

There was Cash Hyde, the boy whose Stage 4 brain cancer went into remission after his parents snuck cannabis oil into his feeding tube.

There was the “miracle baby” with oil on his pacifier whose brain tumor vanished.

And there was Charlotte Figi, the 6-year-old namesake of Charlotte’s Web, whose 300 seizures a week dwindled to three a month with cannabis oil.

No scientific proof linked their recoveries to marijuana, but Kristen clung to the possibility, her stack of printed stories growing alongside her panic.

“I’m going to watch him suffer. I’m going to watch him die,” she said. “I’m going to see my child getting robbed of the person that he was.”

A few days before Valentine’s Day, she called Joe at work, the words spilling out.

“I just feel like renting a car and going right now,” she said. She needed to see what it was like in Denver. She needed to know they had tried everything.

“If you’re the one that holds me back, Joe, I don’t know if I could live with you.”

“Go,” he said. “Absolutely, go.”

♦

Kristen set off with her mother that night, leaving Tyler with Joe at home.

She was determined to give Tyler a trial run of cannabis with his upcoming radiation treatment. But getting the card Colorado requires to buy medical marijuana would take weeks.

A friend’s boyfriend who already had a card agreed to help. He visited dispensary after dispensary, asking, “What would you give a 5-year-old with a brain tumor?”

Watch:

The Yeckley Family One Year Later

He walked out of one with $1,800 worth of golden cannabis oils in two dozen little bottles.

In the past two decades, 25 states have legalized medical marijuana, often by referendum. Critics call it “medicine by popular vote.”

What has emerged is a patchwork of laws that sidestep the scientific vetting normally required to bring medicine to patients, even as marijuana’s benefits and dangers remain cloudy. Many researchers clamor for more stringent study. The Drug Enforcement Administration vowed earlier this month to make researching marijuana easier, but significant bureaucratic and financial barriers remain.

Meanwhile families cling to anecdotes about a miracle cure for their children.

“Their families are devastated and exhausted trying to care for them and trying to provide the best possible medicine,” said Dr. Larry Wolk, head of Colorado’s health department, who estimates that several hundred out-of-state families have come hoping to help their children. “We just have to be really careful that we’re not throwing the door wide open and saying this is medicine and that there’s science to prove it, because it’s not either.”

It was a long shot, Kristen knew, but the oil in those vials gave her an antidote to her despair. She mapped the quickest route home to Tyler, through six states that ban broad medical use.

First came Kansas, where authorities are fighting to stem the flow of pot from Colorado. Crossing the border, Kristen and her mom became drug traffickers, risking hundreds of thousands in fines and years in prison. They stuffed ski jackets in the backseat. Just a mother-daughter trip to the mountains.

As they drove, sleek, unmarked sport utility vehicles barrelled up the rural highway, then matched pace next to their car. They held their breath as cops scanned their faces, then sped away.

♦

At home, unscathed, their clinical trial of one could begin.

Most kids are given anesthesia before radiation, but Tyler, now 5, said he didn’t need it. “That sounds easy,” he said.

When his playlist of pop anthems came on, Tyler knew not to wiggle under his pink PAW Patrol mask. As Katy Perry sang — I got the eye of the tiger, a fighter, dancing through the fire — Kristen watched on camera as he held perfectly still.

“I will never forgive you if our son dies. I’ll always think about: ‘What if I had done this?’ ”

The Yeckleys had been the first family ever to approach Tyler’s radiation doctor at Florida Hospital Tampa about using medical marijuana.

“She was very clear about what she wanted to accomplish for him, and that was okay with me,” said Dr. Harvey Greenberg.

Kristen wanted to make Tyler’s tumor disappear. Short of that, she hoped cannabis would curb the loss of appetite and nausea brought on by radiation.

At first, lethargic and dazed, Tyler vomited every day. Then Kristen started slipping drops of oil under his tongue.

Almost instantly, his nausea ceased.

♦

It seemed like Tyler was back, teasing Kristen, playing with his trains, his eyes straighter.

“There’s a peanut in my brain,” he would say. He called himself “Shrinker,” for what he wanted to do to it.

Joe and Kristen couldn’t know whether the cannabis oil was helping Tyler. Kristen’s gut told her it was, but their supply in Florida was temporary. Radiation’s benefits would be temporary.

So on the back porch with Joe in early March, she floated the idea of moving to Denver.

Joe didn’t know how moving would work. Would he quit his job, its demands the one thing keeping him sane? Could he find a new job, with health insurance, that would pay well enough for them to afford Denver? Their friends and family, their support network, the life they had built together were all in Florida.

With so much about the coming months still uncertain, they decided Kristen would go to Denver with Tyler when radiation ended. Joe would fly out as often as he could. Neither knew how long they might be apart.

“I never want to look back and say, ‘What if?’ ” Kristen told Joe. “I will never forgive you if our son dies. I’ll always think about: ‘What if I had done this?’ ”

♦

Kristen found a three-story walkup in Denver’s historic Capitol Hill neighborhood, the rent steeper than their mortgage. Tyler hung photos and played with his Disney monorail set. He and Kristen did art projects on the dining room table, like at home.

Here, after getting his drops, he crawled in bed with her each night.

Kristen filled their days with singalong sessions at the library, trips to the putt-putt course, museum visits. She taped words to the wall — “the,” “to,” “Mommy,” “Daddy” — and taught Tyler lessons about animals and states.

At Tyler’s new hospital, she felt she could be honest about why they had come to Denver. Doctors at Children’s Hospital Colorado don’t recommend medical marijuana, but neither do they discourage it.

“A lot of the families are frustrated because they don’t have the time to wait,” said Dr. Katie Dorris, Tyler’s pediatric neuro-oncologist at Children’s. “When they’re faced with a terminal diagnosis, they feel like they have to consider everything.”

Sometimes, though, a nagging anxiety crept in.

Am I being too selfish? Kristen worried. What if I’m robbing Joe of this time with our son?

She was used to homemade dinners and three plates at the table. She was used to Joe bursting through the front door, to Tyler squealing “Daddy!” and hugging his legs. At home, she knew, Joe was opening the door to an empty house.

Tyler didn’t understand why he had to be so far from his friends.

“If Mommy has this medicine in Florida, Mommy could get arrested,” Kristen explained.

“Why?”

“Because this medicine isn’t allowed in Florida. It’s a Colorado medicine.”

“I won’t tell anyone,” he promised.

♦

On Mother’s Day, a couple of weeks after the move, Kristen strapped Tyler into the car and drove to a Denver CVS.

Tyler desperately wanted a sibling, a sister. Joe and Kristen didn’t want to give that up. But this was not expected, not now.

Years before, they had been on vacation in Maryland when they realized Kristen’s inability to stomach a single blue crab heralded something else. When the pregnancy test came back positive, they rejoiced, terrified and elated.

This time, Kristen texted Joe a picture from across the country: Two lines on the pregnancy test. A yes.

Tyler asked a million questions. Joe and Kristen shared their joy over a long distance call.

Kristen bought Tyler a “ROCKIN’ BIG BRO” T-shirt and mirrored aviator sunglasses that covered his crossed eyes. They picked out a pink onesie and a blue skirt with tiny fabric flowers.

Each day afterward, Tyler put his hands on his mother’s belly.

“I hope you’re a girl,” he would say. “I can’t wait to meet you.”

♦

As the spring wore on, Kristen started having to carry Tyler up the stairs to their apartment. Instead of clambering out of the tub, he began reaching for her steadying hand.

How do I call Joe and say, “I think Tyler’s eye is turning in, I think he’s more lethargic”? Kristen worried. She could barely admit his worsening condition to herself.

When graduation photos of Tyler’s pre-K classmates popped up online, rosy-cheeked in their caps and gowns, Kristen felt a renewed sense of isolation.

For all of Colorado’s benefits, Kristen kept thinking, a parent shouldn’t be forced to live this way.

Something had to change, Joe told Kristen on a visit to Denver in late May.

“We’re doing one of two things,” he said. “Either you’re coming home, or I’m coming out here. I don’t want to be apart anymore.”

They weighed dozens of pros and cons in the days that followed, rehashing the sacrifices they were making, the risks of returning to Florida. They researched Denver real estate, jobs, neighborhoods, envisioning a life there.

Tyler listened to his parents talk.

He missed his friends at home, who were his safe ground, the ones who knew his new limits. Unlike some kids on the Denver playground, they would never ask him, “Why’s your eye like that?” They were the ones who knew why his smile was gone.

He chimed in with his own idea.

“Well, you and Daddy can live here, but I want to go home,” Tyler said. “I really want to be with my friends.”

♦

Tyler’s words weighed on Kristen.

In the back of her mind, she felt she wasn’t done with Colorado. The doctors in Denver were making plans and gave her a sense that there were options. But she didn’t have the will to keep telling her son no.

They’d return, she and Joe decided, when the apartment lease ran out in late June. Largely, though, they’d finish out the time apart, Tyler still asking about his friends, Kristen still hoping for a miracle.

Kristen spent one day in early June trying to find a moment to call Joe with updates from Tyler’s latest MRI without Tyler eavesdropping. She decided on a trip to the playground, where he would be distracted.

She settled in as Tyler scurried around, playful but clumsy, his vision doubled. He reached for the firefighters’ pole, trying to wrap his legs around it, but his grip faltered. Kristen watched as her son crashed to the ground.

Tyler, who never complained, screamed out in pain.

Kristen rushed to him, scooping him up from where he had landed on his foot. They had walked to the park, leaving her wallet behind. Calling an ambulance would cost hundreds. She was pregnant. Tyler was sobbing.

All of the people she would have called for help were thousands of miles away.

♦

Kristen stood in the living room and took it all in.

She and Tyler had flown to Florida for a planned visit in June. Raindrops streaked the windows. Lasagna bubbled in the oven. Tyler’s friends crashed through the room, raining foam bullets on their parents, shrieking, ducking and laughing.

Tyler knelt on the carpet in a blue cape, struggling to spring-load his Nerf gun. His foot was still healing after the playground fall, so he crawled like a toddler. “Mommy, mommy,” he pleaded.

Kristen tussled with him and grinned. “You’re T-Man, aren’t you?”

Joe laughed, begging them not to get a bullet stuck on the skylight.

Tyler giggled. Kristen looked up. “Already did.”

Later, the kids snuggled in a pile of blankets as Happy Feet splashed blue light on the walls. Kristen crouched beside Tyler, sleepy and faraway, and slipped the dropper under his tongue. Fourteen drops tonight.

She had needed to know that she’d given her son every chance before coming home. Now she felt sure. And after all of her efforts to recreate home in Denver, here was the real thing.

♦

Despite her late-night fears anticipating the trip home, Kristen, her mother and Tyler got through the white-knuckled drive undetected, their two-month Denver adventure come to an end. Along the way, Tyler tried on cowboy boots in Texas and collected rocks from each state, getting closer to his friends with each one.

Back in Florida, Joe often woke to Tyler by the bedside, clutching his blankie and stuffed puppy. Sometimes Tyler slept in the hallway outside their bedroom door until Joe acquiesced, sweeping his son into the bed with him and Kristen.

Tyler kept taking his drops. Their Colorado doctor was arranging a clinical trial to study the palliative effects of medical marijuana. Talk of the future spooled out, into August, September, Christmas, next year.

An early ultrasound showed the baby would be a boy, though Tyler still whispered his wish for a sister. Kristen and Joe chose the name Jayson, “the healer.”

Tyler’s parents weaned him from his oil for a Make-A-Wish Foundation Disney cruise in early July, worried about bringing it into international waters. He vomited a few times, but still had the energy to ride the Aqua Duck water slide and hunt down a signature from Pluto.

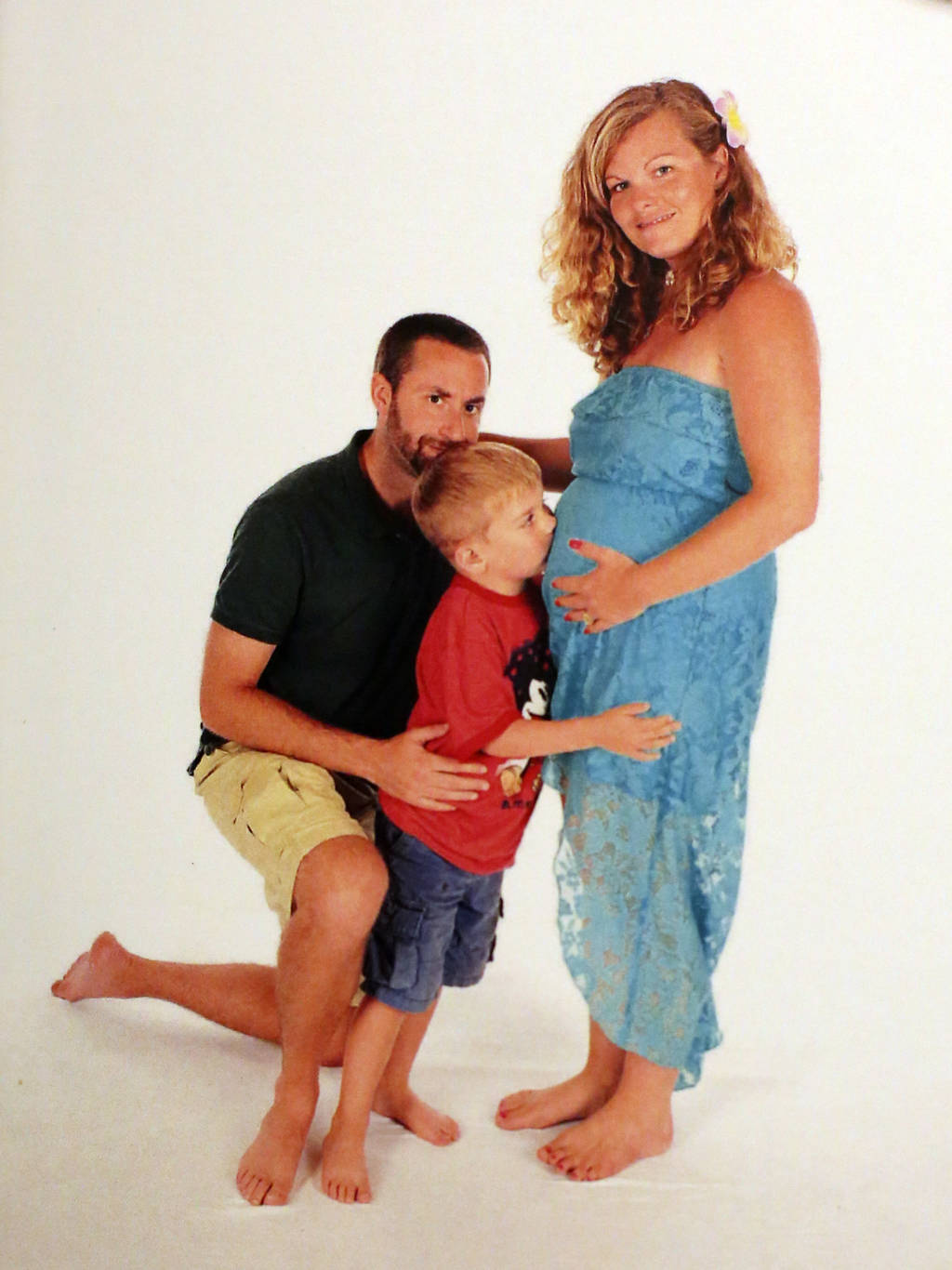

The Yeckleys returned with a new family portrait: Kristen’s blond hair pinned behind one ear, Tyler kissing her round belly, Joe crouched beside his son — the four of them.

♦

Tyler fell three times in the days after the cruise.

He tripped over his train tracks. He slurred, so tired he couldn’t make it through the day without napping for hours. Favorite games like Sorry didn’t interest him anymore. At night, his breathing became thick and raspy.

“It’s not going away,” Kristen said one morning in tears.

This can’t be happening, Joe thought.

Kristen spent one night searching: How do you know when it’s the end?

They took him to the emergency room. The cancer had spread.

Tyler would have to go into surgery to relieve pressure in his brain. Kristen remembers the scans, splattered with tumors.

♦

The hospital room was dark and still when Kristen woke early the day of her son’s surgery. Tyler was already awake. Kristen nudged Joe.

“What if there’s no tomorrow?” she asked. She needed this baby to know just how much Tyler was looking forward to his arrival.

Together, the three of them compiled a list on Joe’s laptop.

Why Tyler is excited to be a big brother.

- Play trains.

- Play school.

- Watch Disney movies.

- Take him on Jeep rides.

- Show him Chuck E Cheese.

- Sleepovers in his room.

♦

The oxygen machine purred at the bedside. Curled in the sheets, Tyler dozed in blue Mickey Mouse pajamas, a buoy afloat in the expanse of his parents’ bed. It was late July, seven months since the diagnosis. His small hand grasped Kristen’s finger.

With tired eyes, she bent close.

“Do you have to go potty? Thumbs up, thumbs down,” she asked, voice bright. “Do you want to walk? Thumbs up, thumbs down. Yes. Okay, let’s do it.”

She had been trying not to cry around Tyler, trying not to let him sense her grief and fear. The night before, after surgery, Tyler’s coughing had tilted into violent, unbearable rasping, his lungs straining to regain control.

“Are you ready, baby?” she said. “If you get in a lot of pain, squeeze my hand hard. Okay?”

Joe eased Tyler from the bed. Shades muted the sharp afternoon sun, casting the room in a dim blue. He held Tyler by the underarms and tried to waddle him to the bathroom.

Trailing tubes, Tyler kept coughing wet, weary coughs.

“Good job. Nice and slow,” Kristen said. “Look at those feet moving.”

♦

Kristen listened to her son’s slow breathing.

He had been in hospice care a few days. The day before, he had said, “I love you.”

“Are you scared?” she had asked. He gave a thumbs down.

“Are you tired of hearing that you’re brave?” Thumbs up.

She and Joe held him in their bed and knew he was listening.

“We want you to meet us in your dreams every night and ride the Aqua Duck, and if you get tired of that, you can meet us at the Disney campground,” they said. “In heaven, there will be no more cancer.”

She and Joe promised that Mommy and Daddy would take care of each other, even when it was very hard.

“Mommy can’t make you better anymore,” she said. “It’s okay to go.”

♦

Reminders found them everywhere in the strange, bruised months after Tyler died. The Nerf dart still stuck on the skylight. Wheeling the shopping cart past the Lunchables Tyler had always begged Kristen to buy.

Kristen kept the photos on her phone, each one a memory. Out west, Tyler had gotten to throw snowballs, ride trains and see the Rockies. He had curled up with his mom each night, had picked out the pink onesie for his dream of a sister.

In the chasm of her grief, Kristen took a small comfort in knowing she had tried everything. Even in her deepest moments of despair, she knew she wouldn’t have done a single thing differently.

In mid-August, she and Joe went for a 20-week checkup on her pregnancy. They saw pictures of the new baby's heart and spine. Kristen mentioned the boy on the way.

The ultrasound technician paused.

“No, I don’t think so,” the technician said. “I think it’s a girl.”

“Are you sure? It’s a girl?”

“You see those three lines right there? That’s a girl.”

One of Tyler’s great ideas come to pass.

Epilogue

Jayda Yeckley was born in December 2015 with fine blond hair and a button nose like her brother’s. Kristen and Joe hope to give her a sibling.

More than a year after Tyler’s death, the law now allows dying patients in Florida access to some forms of medical marijuana, and broader medical use will again be on the November ballot. Kristen remains frustrated it wasn’t an option for Tyler here.

And she isn’t sure if she wants to teach again. For now, she wants to stay home with Jayda, knowing what all those small moments are worth.

The Yeckleys still invite Tyler’s friends over. Sometimes, when the kids are playing, Kristen walks into the back yard, into the dusk. She closes her eyes and listens to their giggles, pretending for a moment that Tyler is inside, that she can hear his voice amid the chorus of laughter.

Times news researcher Caryn Baird contributed to this report. Designed by Lauren Flannery. Contact Claire McNeill at [email protected] or (727) 893-8321. Follow @clairemcneill.