In a soft-furnished studio space behind a warehouse in west Berlin, a group of international scientists are debating our robot future. An engineer from a major European carmaker is just finishing a cautiously optimistic progress report on self-driving vehicles. Increasingly, he explains, robot cars are learning to differentiate cars from more vulnerable moving objects such as pedestrians or cyclists. Some are already better than humans at telling apart different breeds of dog. “But of course,” he says, “these are small steps.”

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Then a tall, athletic man with a light-grey three-piece suit and a greying goatee who has spent most of the morning playing with his smartphone strides to the podium, and suddenly baby steps become interstellar leaps. “Very soon, the smartest and most important decision makers might not be human,” he says, with the pitying smile of a parent explaining growing pains to a teenager. “We are on the verge not of another industrial revolution, but a new form of life, more like the big bang.”

Jürgen Schmidhuber has been described as the man the first self-aware robots will recognise as their papa. The 54-year-old German scientist may have developed the algorithms that allow us to speak to our computers or get our smartphones to translate Mandarin into English, but he isn’t very keen on the idea that robots of the future will exist primarily to serve humanity.

Instead, he believes machine intelligence will soon not just match that of humans, but outstrip it, designing and building heat-resistant robots that can get much closer to the sun’s energy sources than thin-skinned Homo sapiens, and eventually colonise asteroid belts across the Milky Way with self-replicating robot factories. And Schmidhuber is the person who is trying to build their brains.

As we lower ourselves on to a pair of beanbags after his talk, Schmidhuber explains that in a laboratory in Lugano in the Swiss Alps his company Nnaisense is already developing systems that function much like babies, setting themselves little experiments in order to understand how the world works: “True AI”, as he calls it. The only problem is that they are still too slow – around a billion neural connections compared with around 100,000bn in the human cortex.

“But we have a trend whereby our computers are getting 10 times faster every five years, and unless that trend breaks, it will only take 25 years until we have a recurrent neural network comparable with the human brain. We aren’t that many years away from an animal-like intelligence, like that of a crow or a capuchin monkey.”

How many years, exactly? “I think years is a better measure than decades, but I wouldn’t want to tie myself down to four or seven.”

When I ask how he can be so confident about his timetable, he launches the hyperdrive. Suddenly we are jumping from the big bang to the neolithic revolution, from the invention of gunpowder to the world wide web. Major events in the history of the universe, Schmidhuber says, seem to be happening at exponentially accelerating intervals – each landmark coming around a quarter of the time of the previous. If you study the pattern, it looks like it is due to converge around the year 2050.

“In the year 2050 time won’t stop, but we will have AIs who are more intelligent than we are and will see little point in getting stuck to our bit of the biosphere. They will want to move history to the next level and march out to where the resources are. In a couple of million years, they will have colonised the Milky Way.”

He describes this point of convergence as “omega”, a term first coined by Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit priest born in 1888. Schmidhuber says he likes omega “because it sounds a bit like ‘Oh my God’”.

Schmidhuber’s status as the godfather of machine intelligence is not entirely undisputed. For a computer scientist, he can sometimes sound surprisingly unscientific. During his talk in Berlin, there were audible groans from the back of the audience. When Schmidhuber outlined how robots would eventually leave Earth behind and “enjoy themselves” exploring the universe, a Brazilian neuroscientist interrupted: “Is that what you are saying? That there is an algorithm for fun? You are destroying the scientific method in front of all these people. It’s horrible!”

When asked about those reactions, Schmidhuber has that pitying look again. “My theses have been controversial for decades, so I am used to these standard arguments. But a lot of neuroscientists have no idea what is happening in the world of AI.”

But even within the AI community, Schmidhuber has his detractors. When I mentioned his name to people working on artificial intelligence, several said his work was undoubtedly influential and “getting more so”, but also that he had “a bit of a chip on his shoulder”. Many felt his optimism about the rate of technological progress was unfounded, and possibly dangerous. Far from being the true seer of the robot future, one suggested, Schmidhuber was pushing artificial intelligence to a destiny similar to that of the Segway, a product whose advent was hyped up as a technological revolution akin to the invention of the PC and ended up as a slapstick prop in Paul Blart: Mall Cop.

To understand why Schmidhuber yo-yos between prophet and laughing stock, one has to dive deeper into his CV. Born in Munich in 1963, he became interested in robotics during puberty, after picking up rucksacks full of popular science books and sci-fi novels from the nearby library – Olaf Stapleton’s Star Maker, ETA Hoffmann’s The Sandman and the novels of Stanislaw Lem were particular favourites.

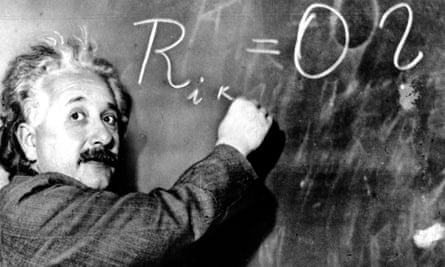

His great hero, “my wonderful idol”, he says, was Albert Einstein. “At some point I realised I could have even more influence if I built something that is even smarter than myself, or even smarter than Einstein.” He embarked on a degree in mathematics and computer science at Munich’s Technical University, which handed him a professorship at the age of 30.

In 1997, Schmidhuber and one of his students, Sepp Hochreiter, wrote a paper that proposed a method for how artificial neural networks – computer systems that mimic the human brain – could be boosted with a memory function, by adding loops that interpreted patterns of words or images in the light of previously obtained information. They called it Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM).

At the time, AI was going through a prolonged “winter”: technology had failed to live up to the first wave of hype around artificial intelligence, and funding was hard to come by. In the 1960s, the hope had been that machines could be coded top-down to understand the world in all its complexity. If there is a new buzz now, it is around a seemingly simpler idea: that machines could be fitted with an algorithm that is relatively basic, but enables them to gradually learn bottom-up how complex the world really is.

In 1997, Schmidhuber’s paper on LSTM was rejected by MIT, but it now looks like one of the key concepts behind a new wave of interest in deep learning. In 2015, Google announced it had managed to improve the error rate of its voice recognition software by almost 50% using LSTM. It is the system that powers Amazon’s Alexa, and Apple announced last year that is using LSTM to improve the iPhone.

If Schmidhuber had his way, the concept would get even more recognition. In a scathing 2015 article, he complained that the “Canadian” trio of computer scientists hailed in Silicon Valley as the superstars of AI – Geoffrey Hinton (Google), Yann Lecun (Facebook) and Yoshua Bengio (IBM) – “heavily cite each other”, but “fail to credit the pioneers of the field”.

During his talk in Berlin and our interview, he repeats emphatically, at regular intervals, like a jingle crashing through your Spotify stream, that the current buzz around computer learning is “old hat” and that LSTM got there many years earlier. He is quick to talk down the importance of Silicon Valley, which he feels is so dominated by “cut-throat competition” that it produces less value for money than European institutes.

One possibility that presents itself when listening to Schmidhuber talk about the future of robotics is that his relentless techno utopianism is simply a strategy to make sure he doesn’t end up as the Sixto Rodriguez of AI, influential but overlooked while the Silicon Valley Dylans go down in the hall of fame.

And relentless it is. Given his interest in sci-fi, has he never worried that robots will enslave and rule over us once they become self aware? Schmidhuber shakes his head. “We won’t be enslaved, at the very least because we are very badly suited as slaves for someone who could just build robots that are far superior to us.” He dismisses The Matrix, in which imprisoned humans are used to power AIs: “That was the most idiotic plot of all time. Why would you use human bioenergy to power robots when a power station that keeps them alive produces so much more energy?”

But in that case won’t robots see it as more efficient to wipe out humanity altogether? “Like all scientists, highly intelligent AIs would have a fascination with the origins of life and civilisation. But this fascination will dwindle after a while, just like most people don’t understand the origin of the world nowadays. Generally speaking, our best protection will be their lack of interest in us, because most species’ biggest enemy is their own kind. They will pay about as much attention to us as we do to ants.”

I wonder if the analogy is less comforting than he intends. Surely we sometimes step on ants? Some people even use chemicals to poison entire colonies. “Of course, but that only applies to a minute percentage of the global ant population, and no one seems to have the desire to wipe all ants off the face of this Earth. On the contrary, most of us are pleased when we hear there are still more ants on the planet than humans, and most of them are in the Brazilian jungle somewhere.

“We may be much smarter than ants, but the overall weight of humans on this planet is still comparable to the overall weight of all ants,” he says, citing a recently disputed claim by the Harvard professor Edmund O Wilson.

Let’s forget about sci-fi, I say. What about more immediate concerns, like robotisation creating mass unemployment? In a recent article in Nature magazine, AI research Kate Crawford and cyberlaw professor Ryan Calo warned that the new wave of excitement about intelligent design was creating dangerous blindspots when it came to the social knock-on effects of replacing humans with robots.

Again, Schmidhuber is not unduly concerned. The dawn of the robot future was clear to him when he fathered two daughters at the start of the millennium, he says. “What advice do I give them? I tell them: your papa thinks everything will be great, even if there may be ups and downs. Just be prepared to constantly do something new. Be prepared to learn how to learn.”

“Homo ludens has always had a talent for inventing jobs of the non-existential kind. The vast majority of the population is already doing luxury jobs like yours and mine,” he says, nodding towards my notepad. “It’s easy to predict which kind of jobs will disappear, but it’s difficult to predict which new jobs will be created. Who would have thought in the 1980s that 30 years later there would be people making millions as professional video gamers or YouTube stars?

“Even highly respectable jobs in the medical profession will be affected. In 2012 robots started winning competitions when it came to screening cancer with deep neural networks. Does that mean doctors will lose their jobs? Of course not. It just means that the same doctor will treat 10 times as many patients in the same time he used to treat one. Many people will gain cheap access to medical research. Human lives will be saved and lengthened.”

Countries with many robots per capita such as Japan, Germany, Korea or Switzerland, he proposes cheerfully, have relatively low unemployment rates. I try to suggest that a truck driver in his 50s who has never heard of JavaScript may not quite share his optimism, but it’s difficult to talk about the concerns of generations, not to say individuals, when arguing with someone who thinks in omega leaps.

Whenever you try to drill into Schmidhuber’s optimistic vision of the robot future, you encounter at its core a very simple scenario. When two beings have a conflict of interest, he says, they have two ways to resolve it: either by collaboration or through competition. Yet every time we encounter such a fork in the road in our conversation, collaboration wins out.

When I ask him whether robots of the future, on top of being curious and playful, will also be able to fall in love, he agrees, because “love is obviously an extreme form of collaboration. The love life of robots will be polyamorous rather than monogamous: “There will be all sorts of relationships between robots. They will be able to share part of their minds, which humans currently can’t, or only if they dedicate a lot of time to each other. There will be fusions of the kind that don’t exist among biological organisms.”

If love is really just an intense form of collaboration, why does it feel so irrational? Why do we feel lust, or heartbreak? Schmidhuber doesn’t pick up the bait. “We’ve already got pain sensors, so that robots hurt themselves when they bump into something. And we’ll work out the lust thing eventually. In the end, they amount to the same thing.”

What if one company, an Apple or a Google, builds up a monopoly stronghold over the supersmart robots that run the world in the future? He thinks that kind of dystopia, as evoked in Dave Eggers’ novel The Circle, is “extremely unlikely”. Here too collaboration will triumph. “The central algorithm for intelligence is incredibly short. The algorithm that allows systems to self-improve is perhaps 10 lines of pseudocode. What we are missing at the moment is perhaps just another five lines.”

“Maybe we will develop those 10 lines in my little company, but in these times, when even Swiss banking secrecy is nearing its end, it wouldn’t stay there. It would be leaked. Maybe some unknown man somewhere in India will come up with the code and make it accessible to everyone.”

If that sounds a little bit Pollyannaish, it’s because Schmidhuber’s own experience – the initial rejection of LSTM and his pervading distrust of “cut-throat” Silicon Valley – must have taught him that competition can create losers as well as winners. As disarming as his optimism can be on a personal level, I would feel a lot more comfortable with the idea of the most advanced beings of the future being midwifed by Jürgen Schmidhuber if he was willing to articulate that doubt.

He ends our conversation on an apologetic note: “I am sorry you are talking to such a teenager. But I’ve been saying the same things since the 70s and 80s. The only difference is that people are now starting to take me seriously.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion