Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Dal is as common in India as pasta in Italy. Find out why this nourishing dish is a classic comfort food for yogis.

When I lived at an American yoga ashram in my early 20s, it had a distinct scent. I soon discovered it was one part incense, one part the ineffable divine, and one part dal—the spiced, soupy, legume-based vegetarian stew adored throughout India and beyond. Although the cooks at this strict ashram where celibacy was practiced nixed the usual garlic and onions—they felt some spices amped up the agni (internal heat), if you know what I mean—the dal was still packed with flavor. Split lentils were cooked to a creamy mush that mingled with turmeric, cumin, coriander, and ginger—all served over a plate of steaming basmati rice. After a long afternoon of yoga and volunteer work, it was so satisfying to slide my spoon into the fragrant, savory porridge. Like when I first discovered yoga, I found the meal to be deeply nourishing, satisfying, and a little bit thrilling—that moment when you realize something good for you can feel just as or even more exciting than the naughty stuff.

Years later, I learned it wasn’t just my yoga high (or the lack of sugar and sex) that made dal seem indulgent and healing. Dal—which derives from the Sanskrit word dhal and means “to split”—appeals to yoga practitioners of yore and today alike because it’s considered a nutritious part of the sattvic, or pure, diet. “The philosophy of yoga avoids indulgence and supports mitahara, the concept of moderation in diet,” says Kantha Shelke, a food scientist based in Chicago who comes from a yoga-practicing family. Mitahara is a yogic tenet encouraged in ancient texts, including the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, a Sanskrit manual on hatha yoga. The low-cost, high-nutrient legume fits into this notion. “Dal’s a powerhouse of nutrition that nourishes the body while delighting the senses,” says Shelke. In other words, it’s an ideal food for those looking to create balance in their bodies and lives—like yogis.

Check your pulse

Like yoga itself, dal is ubiquitous in India. As an inexpensive, vegetarian, and simple-to-cook protein, this staple is consumed by the poor, wealthy, young, old, and everyone in between. “Dal is the key to every Indian meal—it’s always there,” says Anupy Singla, author of three Indian cookbooks, most recently Indian for Everyone.

In India, a watery, spice-free moong dal is usually a baby’s first food because it’s easy to digest and nutritious. Dal is also considered tri-doshic in Ayurveda—the ancient Indian system of healing and sister science to yoga—which means it suits every dosha, or your unique physical and mental constitution that influences well-being. People with Indian parents will tell you how as children, illnesses like stomachaches and flus were treated at least partially with dal; Indians often call it the chicken soup of India. And yogis in India and the West often use one riff on dal, a spiced stew of lentils, rice, and ghee (clarified butter) called kitchari, to break fasts or as the only food they eat during a fast.

Like chili aficionados in the United States, Indian cooks create hundreds of regional and household variations on dal. Although people throughout India use the same five or so legumes or pulses—an umbrella term for lentils, beans, and peas—the hot oil-spice blend known as the tarka varies a lot. (The tarka is made by cooking ghee or hot oil with whole spices or a spice blend—masala—in a small skillet.) For example, explains Singla, in Southern India you’ll find a stew-like vegetable dal, or sambar, made with split pigeon peas (toor dal) or chickpeas (chana dal); a Southern Indian tarka is likely to include mustard seeds and curry leaves. Head to a northern state like Punjab and tarka is made with cumin seed, onion, ginger, garlic, and some garam masala, a warming spice blend best in cooler weather. On the coast in tropical Kerala, where coconuts are abundant, you might find dal made with coconut milk.

In addition to signaling a dal’s origin, the choice of legumes also dictates nutrition and preparation—the more intact or whole the pulse, the more nutrients and the longer the cooking time. And although the word dal means “to split,” some dal legumes are cooked whole. For example, the salmon-colored, split red lentil (masoor dal) takes about 12 minutes to surrender into an ideal porridgelike consistency, but the same lentil in its whole, brown, uncooked, unsplit state can take up to 45 minutes.

See also Chickpea Dal Recipe

Bring it home

One essential step in preparing dal is cooking it long enough. “In the West, we���re taught that lentils should be al dente,” says Singla. “But in the South Asian community, we prefer it like porridge, unless the recipe calls for something else.” Singla, who was born in India and visited frequently after she moved to the United States at age three, recommends cooking legumes a little longer than you think you should—moving beyond “lentil salad” to an “oatmeallike” zone. Also, it helps to have fresh legumes, which take less time to melt into mush than those from a dusty bag. Singla clears legumes in her pantry when they reach four years old.

And to turn a simple lentil porridge into a masterpiece of flavor, focus on the tarka. Beware, however: Heat the spices too long and your delicious blend can quickly become a charred mess; too short, and the flavors won’t bloom. To avoid kitchen disasters, stick to the ingredient order listed in the recipe, and keep in mind that cooking goes quickly—the entire tarka-making process takes only two to three minutes. “Never leave that pan,” says Singla. When the oil or ghee is hot, add whole spices like coriander seeds and cumin seeds; they should start to sizzle. At about 30–40 seconds on medium-high, or when the spices become reddish brown and aromatic, add the onion, ginger, and/or garlic, and then add powdered spices at the end because those tend to burn easily.

On its own, dal could surely get as boring as pasta is to some Westerners. But like that bowl of plain noodles, the variations are almost endless. And unlike those pure carbs, dal offers a much more complex, nourishing nutritional profile—all of which can make dal a yogi’s dietary best friend. Singla’s family, which eats some kind of dal every night, often laments, “Lentils again?” But, says Singla, “There is a magic that happens when the tarka hits the lentils, in terms of taste, that makes us go, ‘Why were we saying we didn’t want this? This is the most delicious thing.’ It’s this amazing combination of flavors that’s just addictive.” Start making your own sublime bowls of dal at home with these four simple recipes from Singla.

See also Yellow Lentil Dal

Four Dal Recipes

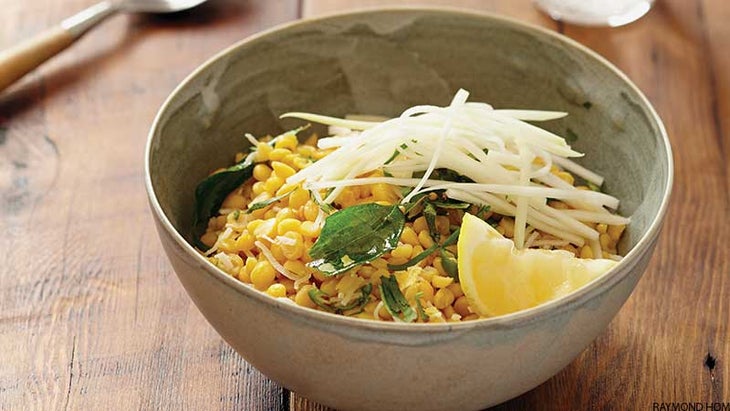

Chana dal sundal

Sundal is a delicious Southern Indian street food served in parks and temples. You can make it with any legume, but it’s most commonly made with chickpeas. Here, cookbook author Anupy Singla uses a split and skinned chickpea called chana dal. She loves making this dish for her kids as an afterschool treat to eat hot at home or cold in the car on the way to soccer practice. For extra sweetness, add ½ cup grated green mango or papaya with the coconut.

Punjabi moong dal

This is a common dal in North Indian Punjabi households.

Slow-cooker dal makhani

Dal with makhan (butter) is a more decadent version of Indian dal that has become a standard, go-to dish on Indian-restaurant menus. It’s at once hearty and comforting. This recipe for a slow cooker makes it that much easier to make and enjoy at home.

Gujarati dal

This dal is made in most households in the region of Gujarat, in Western India. The sweet-and-sour components reflect the importance of sweet notes in food from this region, while nuts add a comforting crunch.

Learn more about TastyBite.