The long, expensive road to justice

A survey by research agency Daksh, made available exclusively to India Today, exposes the reasons for the unconscionable delays in the delivery of justice in India, the unserviceable workload, the harassment of litigants and chronic administrative neglect.

Give me a couple of minutes." This is a much repeated expression in our daily routine. Two minutes. 120 seconds. This tiny snippet of time passes before you know it. It repeats itself between 150 and 300 times before the work day is done. Coffee break, quick phone call, fixing a jammed printer-two minutes isn't usually enough to complete any of these innocuous tasks. However, two minutes is the average time that a judge in the Patna High Court gets to spend on a hearing on a regular day. Two minutes! This is just one of several alarming statistics that Daksh has found in its study of the Indian judiciary.

That cases take a long time in Indian courts is a well-known fact. Why is it so? What can be done to solve this? What does the delay mean from a rule of law perspective? What are its political, social and economic costs? These are some of the critical questions judges, scholars and various commissions have asked but failed to answer definitively. There have been entire Law Commission reports dedicated to the question. However, despite all the discussions, debates and policy suggestions that have gone into tackling this problem, little has changed. If we were to ponder the lack of change, and try to pinpoint reasons, two words come to mind-numbers and ownership.

Why the delay

There is a complete lack of focus on relevant numbers. Apart from the overall number of cases pending in the system (three crore cases is what the media keeps repeating from time to time) and some unscientific and fanciful projections of the time that the judiciary will take to clear the backlog, very little is known about the problem of delay. For example, what kind of cases are clogging the system? Despite judges working extremely long hours, why is that there is no serious dent being made in the mountain of delays? Are judges in one state more efficient than others? How long do different types of cases remain in the system and why? How can we maximise judicial time? Answers to these questions are most important to bring about change. However, no systematic effort has been made until recently to collect data that will help obtain the answers to these questions.

Daksh's Rule of Law project goes a long way in filling the void in judicial data. The Daksh database currently has details of more than 40 lakh cases pending before various courts across the country. The average pendency of any case in the 21 high courts for which we have data is about three years and one month (1,128 days). If you have a case in any of the subordinate courts in the country, the average time in which a decision is likely to be made is nearly six years (2,184 days). Even assuming that a case does not go to the Supreme Court (and a majority of the cases in the system do not), an average litigant who appeals to at least one higher court is likely to spend more than 10 years in court. If your case does go to the Supreme Court, the average time increases by at least three more years. Remember, of course, that we are only talking about averages. If you are unfortunate enough, you could to be on the wrong side of the average. To put things in perspective, our database has revealed cases from the 1940s and 1950s still pending in courts.

The frustration of the litigants is understandable: the uncertainty caused by the delay is troublesome at the least, as it puts a question mark over the issues being litigated in court. A delayed resolution may not be a resolution, after all.

We can see that if you file a case in the Karnataka High Court today, at the very least, you could expect to be in court until the beginning of 2019. In these two years and eight months (969 days), you could expect to go to court about 12-13 times, as the average time between hearings in the Karnataka High Court is 78 days. We can also look at more specific statistics. For instance, regular first appeals (RFAs) constitute seven per cent of the total cases in the Karnataka High Court. On average, RFAs are pending for four years and three months (1,553 days). On the other hand, company petitions, although constituting a mere one per cent of the total cases in the Karnataka High Court, are pending on an average for six years.

Comparison between different courts is another aspect the database allows us to explore. A case is pending on an average for two years and two months (779 days) in the Hyderabad High Court, which has jurisdiction over the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, whose population is 8.5 crore. Contrast this number with Gujarat, with a population of six crore and a high court where pendency averages at a little more than three years and two months (1,163 days). With 2.5 crore more people, how is it possible that the Hyderabad High Court appears to be more efficient than the Gujarat High Court?

The number of judges in the country is a statistic that is typically focused on. But while it is necessary to appoint the sanctioned strength of the judiciary, merely increasing the number of judges will not, on its own, make the problem of pendency disappear. Rather than the judge-to-population ratio, what should be considered is the litigation-to-population ratio. As per the numbers in the Daksh database, the national average cases-to-population ratio (based on data available for 513 of the 683 districts) is 1.77 per cent. Looking at districts that have a low litigation-to-population ratio will help us identify environments that permit low litigation rates. And districts that have higher rates can be staffed better, with more number of judges and better infrastructure.

Dealing with cases quickly is, of course, not the only measure of a good legal system. Cases have to be dealt with fairly and judiciously. This brings us back to where we started, the question of time in the judiciary. Our database tells us that in the high courts in India, judges hear anywhere between 20 and 150 cases a day, averaging at 70 hearings per day. Let us add one more dimension to this statistic, namely working hours. On average, judges spend 5-5.5 hours a day hearing cases. That is, 300-350 minutes. When we put these two numbers together and perform a simple division, we find that the most (relatively) relaxed high court judges in the country have 15-16 minutes to hear each case that comes before them, while the busiest, such as those in the Patna High Court, have only 2.5 minutes to hear a case, and on average, judges have approximately 5-6 minutes to decide a case!

Yes, we are only talking about the average and, yes, judges do spend a lot more time on final-hearing matters or matters that require more attention. But it is impossible to take away the element of unfairness when a human being is asked to decide on issues pertaining to 70 matters. It is not only unfair to the litigants and lawyers (and any practising lawyer will confirm the amount of uncertainty in our courts arising from the sheer volume), but also extremely prejudicial to the judges themselves. No society can ask its judges to work under such stress and expect them to render justice on a daily basis. It is akinto a team chasing 300 runs in a T20 cricket match. Everyone knows it is next to impossible to achieve, and functions with that knowledge, bringing an element of luck and chance to decision-making. In such a chase, the scorecard pressure forces batsmen to throw away their wickets injudiciously. If the chase were reasonable, they might have achieved the target. Similarly, a judge is forced to treat certain matters casually and accept requests for adjournments easily, because he has a long list.

But the judges are not, of course, the most vulnerable victims of this overburdened apparatus. Daksh conducted an Access to Justice survey to elicit the perspectives of litigants, who are the real victims. The survey asked questions, among others, about the dark secret of our criminal justice system-undertrial prisoners spending more time in prison than the prescribed punishment for their alleged offence. About 28 per cent of the accused declared that they had spent more time in jail than the prescribed punishment. Thirty-four per cent of individuals accused of bailable offences claimed that they continue to be in jail as they do not have the means to afford the bail or guarantors to stand surety.

Both these figures are shocking, even providing for margins of error and misplaced perceptions. The judiciary is not solely responsible for the entire criminal justice system, nevertheless these numbers are a sad reflection of the state of affairs.

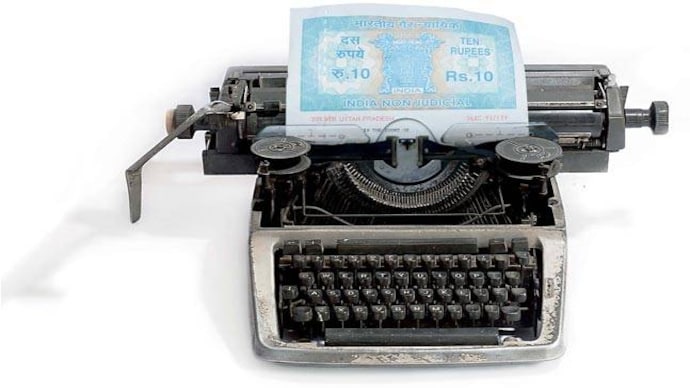

The act of seeking justice and the courts comes at a price. While lawyers' fees and court fees can be quite steep, the personal costs borne by the individual litigant can also be significantly high. The survey sought to measure two costs: a) costs incurred by litigants to come to court for hearings and b) productivity costs arising from their presence in court.

On average, each litigant spent Rs 519 per day to attend court. Assuming a minimum of two litigants per case and multiplying it by the number of subordinate courts in the country (we have taken the number as 16,400, though according to Supreme Court data, there are at least 20,000 subordinate courts in the country) and the average number of hearings per day in each court, we can calculate the total amount of money being spent by litigants just to attend court hearings. Even on such a conservative basis, the amount is Rs 30,000 crore per year! It is staggering by any yardstick. Even more unfortunate is the fact that litigants with an annual family income of less than rs 1 lakh per annum spent 10 per cent of their earnings in attending court hearings, other than legal fees, in a year.

Perhaps this is the reason that 33 per cent of civil litigants interviewed by our survey attested to using alternative means of dispute resolution before approaching the courts. They had approached family elders, village or caste panchayats, or the police to settle matters before going to court. While there is nothing wrong in trying dispute resolution outside courts, the methods used by some of them are extra-legal most of the time, if not downright illegal, attacking the very foundation of access to justice mandated by the Constitution and the rule of law.

The real shocker, however, is the loss of productivity-due to loss of work time, wages and business losses. According to our survey, this loss of productivity is Rs 873 per litigant. Using the same conservative methodology we used to calculate the money spent by each litigant to go to court for each hearing, we computed the productivity loss per year. That number is a staggering Rs 50,387 crore per year! As a national cost, it adds up to 0.48 per cent of India's GDP. If this is not a significant cost of litigation, what is?

Setting it right

So, who is going to fix the problem? Unfortunately, it is not clear. Both the judiciary and the executive are extremely concerned about the issue of judicial delay. In recent days, the President of India, the Chief Justice of India and several cabinet ministers have made public statements about the crisis the judiciary is facing and how the rule of law is being affected. Concern, therefore, is really not the issue. Capacity, power and time are. Today, there is no identified set of people spending time on administering the judicial system, which consists not only of the judges, but also the accompanying bureaucracy that carries out a lot of tasks, which if efficiently done, can increase the efficiency of the system significantly. In the constitutional scheme, the high court (essentially its chief justice, who is the administrative head) has the power of superintendence over the entire judiciary of the state. Unfortunately, the chief justice also performs judicial functions and, as discussed above, is hard-pressed for time even there. Administration consequently does not receive enough attention, except from a few enlightened chief justices, and is largely left to the domain of the registry. The registry is mostly focused on day-to-day processes and does not have the tools or capacity to focus on policy level data collection, analysis or reforms.

Consequently, judicial administration has been orphaned. Unless there is a concerted effort to create an efficient administrative system, no effort at reforming the system will bear fruit in the long run. The failure to properly design and implement the scheme of court managers or take forward the vision of the National Court Management System Committee are glaring examples. The need of the hour is for judicial and political will.

Ramya Tirumalai and Kavya Murthy of Daksh provided research inputs for this article.