The Odd History of the First Erotic Computer Game

Released in 1981, Softporn was controversial, cheesy, and earnest to a fault. It also presaged today's ongoing debates about who computers and games are for.

On October 5, 1981, Time magazine ran a story called “Software for the Masses”—a retrospective meditation on how computing became personal. If 1970s computer ownership had been limited to hobbyists who built and programmed their own machines, the 1980s were reeling in a new world of potential, non-specialist users: small business owners, housewives, children. The possibilities were endless, and for many consumers, overwhelming.

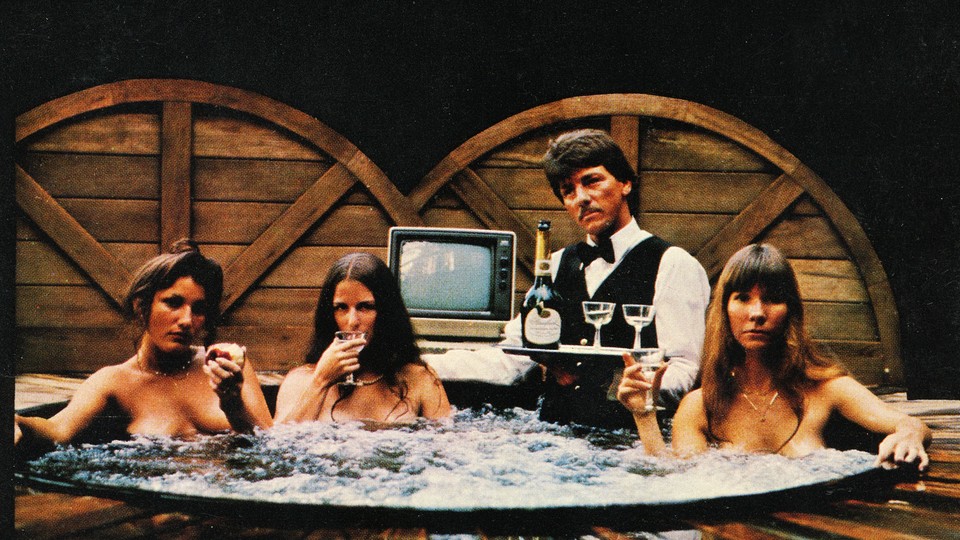

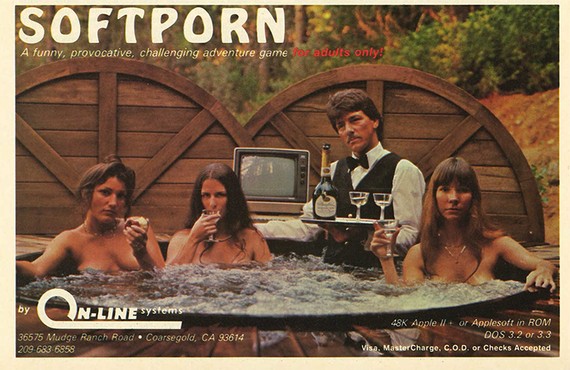

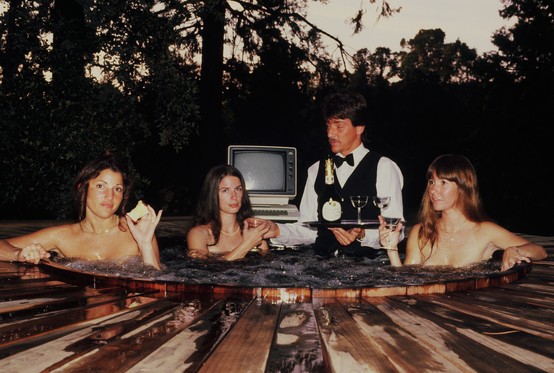

“Software for the Masses” might have been an otherwise arid tech story, buried and forgettable. But it ran with a warm, risqué photo of three brunettes in an outdoor hot tub, their breasts bobbing and nudging the waterline. This image was the promotional photography for the “computer fantasy game” Softporn, in which “players seek to seduce three women, while avoiding hazards, such as getting killed by a bouncer in a disco.” For $29.95 (plus $1 shipping and handling) a company named On-Line Systems would mail out this “funny, provocative, challenging adventure game for adults only!” on a single 5.25-inch floppy disk. Time reported that 4,000 copies had already been sold, making each and every purchaser the proud, unsuspecting owner of America’s first commercially-released pornographic computer game.

Photo courtesy of Sierra Gamers

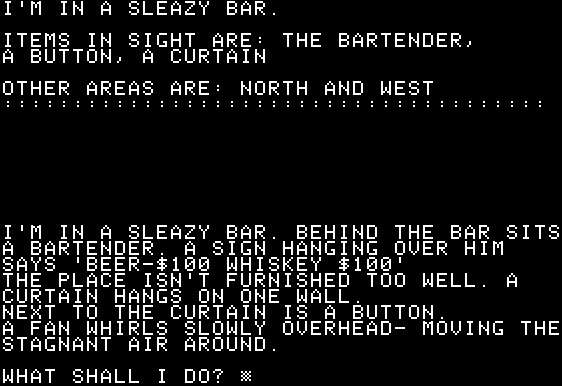

As an erotic episode, Softporn would leave much to the imagination. Softporn was a text-based adventure game, meaning it had no graphics. Upon booting the floppy disk, the player was given control of a “puppet,” a human male through which the player executes textual commands. PLAY SLOTS. BUY WHISKEY. WEAR CONDOM. SCREW HOOKER. Softporn is set in a vague, 70s-infused urban dystopia entirely comprised of a bar, a casino, and a disco. Computer games had escorted players into underground caves, realms of starry space, and sport fields of every kind since the 1960s. Softporn captures a different kind of aspirational landscape, a contorted, pulpy vision of a bachelor’s night on the town.

Softporn was the creation of Massachusetts-based programmer Chuck Benton, an unlikely man to herald the erotic software revolution. A self-described “conservative New Englander,” Benton was a single guy in his late twenties at the time, and he initially designed the game as an exercise to teach himself programming on the Apple II. He intended the game as satire, a self-amused catalog of the unique sufferings of his species—the embarrassment of buying a pack of condoms, or accidentally going home with someone who ties you up and steals your cash (Benton claims parts of the game were drawn from his own experience, but has never fessed up to which parts).

Benton wasn’t trying to innovate on the text adventure genre so much as he was iterating from a pattern of pre-existing games. Many of the game’s cleverest features have the quality of introductory programming exercises: playing the blackjack and slot machine simulators, spending and earning money, a question and answer scenario using basic programming routines, and graffiti on a bathroom wall represented like ASCII art. The game was a silly thing, programmed and play-tested on the weekends, but Benton's guy friends took a liking to it and encouraged him to publish it.

There’s a gawkiness to Benton’s lines and lines of textual description, from the “swinging singles disco” full of “guys and gals doin’ the best steps in town,” to the prostitute’s bedroom, where “the bed’s a mess and the hooker’s about the same!” For all of Softporn’s exhausting chauvinism and wearied sexism, the game is absent of actual obscenity, and earnest to a fault. Even Eve, the final girl sought by the player, is sketched in little more than boyish exuberance: “What a beautiful face!!! She’s leaning back in the jacuzzi with her eyes closed and seems extremely relaxed. The water is bubbling up around her….A ‘10’!! She’s so beautiful………….A guy really could fall in love with a girl like this.”

What is remarkable about Softporn isn't that it existed, but that it was commercially sold. Erotic content had circulated freely on mainframes and minicomputers for decades, whether in the form of dirty joke generators or ASCII print outs of the Playboy bunny head. Raunchy code on a mainframe was available to any curious, specialist user poking around in the file systems. It wasn’t unlike a pin-up girl on the office wall: It could affirm the standard notions of what was and wasn't desirable among male co-workers, but wasn’t necessarily intended to provoke sexual activity. In contrast, microcomputers had an unforeseen potential for privacy, individual use, and personal ownership of code. Eroticism in this context could be illicit and furtive. Softporn was the computational equivalent of a Penthouse stash.

Benton’s initial attempts to sell the game himself faltered in the face of distribution problems: Computer enthusiast magazines, the only network connecting a large but dispersed population of potential buyers, turned down his ads, unwilling to risk already slim profit margins on potentially offensive material. (Such bottlenecks eventually inspired innovations like the 1981 Dirty Book, a black-market-style catalog of adult programs that was advertised in computer magazines—selling a pamphlet of porn software was considerably less objectionable than selling the software itself, it seems.) Benton’s independent sales were painfully hand-to-hand, conducted from vendor booths at trade shows and computer fairs.

and The Art of Sierra)

The boost Benton needed came when Ken Williams, one of the Apple II world’s youngest, most recklessly ambitious software titans, picked up a copy at a trade show. Williams was the 26-year-old president and co-founder of On-Line Systems, a software company he and his wife Roberta had launched with the 1980 release of their graphical adventure game Mystery House (Ken programmed the game but Roberta designed it, making her one of the first female computer game designers in the world). Since then, the Williamses had fostered an indomitable series of graphical adventure games and arcade copycats, long forgotten titles like The Wizard and the Princess and Missile Defense. Ken, along with a handful of other late-twenties fast risers in the Apple II world, experienced their fame as an unstoppable ascent for the best and the brightest. In other words, Ken had both the self-importance and the naivety to put his well-respected company label on a sex game.

On-Line Systems’ contribution to Softporn’s success went beyond the simplicity of a licensing agreement. The game’s visual lacquer, that hot tub photo better remembered today than the game itself, was all Ken’s idea—it was even staged in the Williamses’ redwood paneled hot tub on the ground floor of their family home. The female models were all company employees: Diane Siegal, On-Line's production manager, holds a half-eaten apple in a coy pun on Wozniak's forbidden fruit; in the middle, Susan Davis, On-Line's bookkeeper and wife of programmer Bob Davis; and on the right was Roberta herself, looking as if she had all eternity to meet your gaze. The gentleman in the photo is Rick Chipman, a waiter from The Broken Bit, a restaurant just down the road on California State Route 41.

The photo itself was shot by Brian Wilkinson, an editor at the local newspaper who knew Ken as a guy around town, the kind of guy he might drink beers with. “I’m no Ansel Adams,” he told Ken Williams, “but I can take a photo.” Wilkinson shot multiple reels of Kodachrome and Ektachrome film, but only a handful of those original photos survive. These sparse vignettes give dimension to a process, rather than the singular, famed result that crops up under a Google search. Afternoon fades to sunset fades to evening. The women grow bored and irritated. An apple is slowly eaten over the course of the shoot. A backdrop is propped up, made from the round lids to the pool. At some point the Apple II was either brought in or taken out. No one in that hot tub imagined Time magazine on the other end of the lens. These people were friends, screwing around in the times before Twitter and Instagram, doing regrettable things they couldn’t really fathom the ultimate reach of. There could be no better testament to just how small, insular, and utterly naive the early independent microcomputer software scene was, a corporate culture wrought from the volatile mixture of inexperience and exponential growth.

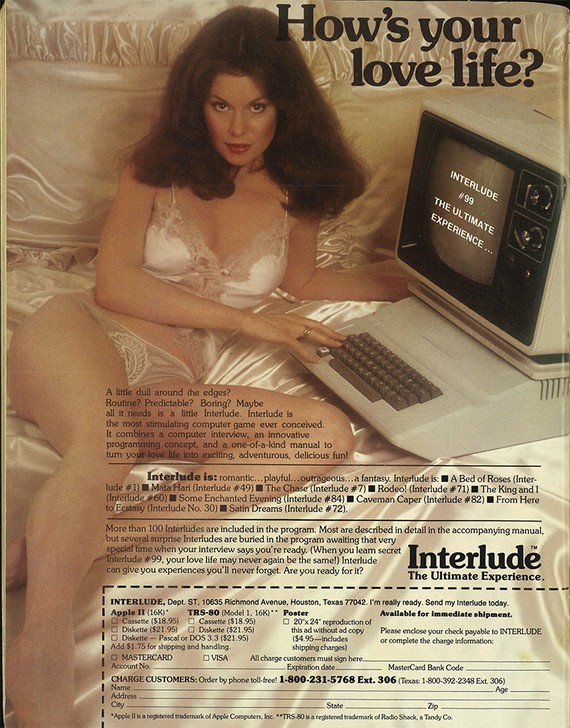

The hot tub ad first ran in the September 1981 issue of Softalk, an Apple II enthusiast magazine that was a major advertising venue for On-Line Systems, and instantly became a lightning rod of controversy (as instantly as anything could happen in the days of paperbound magazines and mailed letters). Notably, the controversy was not just about Softporn. From September 1981 onward, Softalk, like other computer magazines, was increasingly accepting the advertising dollars offered by other “adult-themed” software products, like the sex scenario generator Interlude and prostitution business simulator Street Life. For almost a year, the pages of Softalk’s “Open Discussion” section was a platform for one of the most involved, contentious, long-ranging debates to ever take place on the subject of technology, obscenity, and equality in early game and computer culture.

The earliest responses arrived in the November 1981 issue of Softalk. Richard Gillett of Manhattan, Kansas, accused On-Line of turning the pages of Softalk into “cheesecake,” espousing that:

There are many [Apple] owners with children who read their issue of the magazine. Finding an ad like yours in the magazine must certainly put these parents off. It is bad enough that their children's television viewing hours are riddled with sexual themes and suggestions. Now a child can't even attempt to work with a computer—an essentially sexless tool—without being besieged with these unnecessary ads.

of Softalk Apple Preservation Project

Mary Miller Smith of Doraville, Georgia, complained that the presence of sexually suggestive ads prevented her from using the magazine in her computer literacy class, arguing that “Women will never get out of the bedroom if this type of advertising is continued.” Everyone from programmers to parents to university librarians cast their vote on the adult software debate. Opponents largely critiqued the ads from a social conservative position, suggesting the representations harmed children and did not reflect family values. To a lesser extent, the ads were opposed on the grounds of the feminist anti-pornography politics of the day. In the reverse position, respondents either supported the ads as a form of sex-positive representation, or simply did not believe that representations necessarily built negative social views—as one June 1982 contributor explained, “Sexist views are taught in the home, and in school, not in magazine ads.” Contributors were predominantly (but not exclusively) male, yet concern (or lack thereof) for family, children, and the status of women were the most common refrain. The argument was so extensive, Softalk (whose own editor-in-chief was a woman, Margot Comstock) even defended its editorial decision to run the ads, writing:

In general, it's been a pitiably small minority that have raised their voices to object to these ads. In fact, more than three times as many persons have called with support for carrying those types of ads as have protested. But even more cogent is the point that nothing, not even the pure science of computer programming exists external to the society within which it functions.

Under Softalk's pen, “the pure science of computer programming” was exposed for what it had always been: socially embedded, politically fraught, brittle in its appeal to scientific objectivity. The dialogue around Softporn was perhaps the first time a cultural debate happened within a microcomputing and gaming community itself. Unlike the moral panics that shadowed Custer’s Revenge or Death Race, Softalk’s letter-writers were both consumers and producers of the fledging microcomputer industry, advertisers who were also always its subscribers. In written responses to the ad, readers were sorting through just what they thought their industry should look like, but also questions that were far bigger than microcomputers or games: What is this technology for? What is its potential? How will such images affect the people who see them? What is our responsibility to public good versus individual freedom?

Softalk’s response is a stiff aperitif to the gaming debates of today. What Softporn proves, this most ridiculous, this most unfortunate, this so pitifully blank entry in the history of games, is that friction—between consumers, between industry and consumer, between industry and concerned public—is painful in its moment, but 35 years later only marks how we make new habits and strange technologies familiar. The letters in Softalk, in some backwards way, show that the world of computing was once more diverse than we’ve ever imagined. Women were teaching computer literacy classes in the interstate outskirts of Atlanta, Georgia. Men were defending an ideology of computers as “sexless tools.” Softporn wasn’t the distillation of computing’s misogynist kernel. In 1981 the microcomputer and its allied industries were not already destined to become a space where women are violently harassed for discussing inequity, or simply presumed to have no native interest in technology. Its future was not yet determined, and need not have played out the way it did.

Softporn was pulled within months from On-Line’s advertised catalog, but the circulation of the game was sustained for years between friends and computer communities. Within a year, On-Line Systems would take venture capital and rebrand itself anyway as Sierra On-Line, a company now better remembered for games like King’s Quest, Phantasmagoria, and Space Quest. Sierra On-Line never sold another text adventure. Benton stayed on with the company for a couple years programming ports, but future games of his own didn’t quite get developed (including a female version, which is mentioned in the Time article). He started his own tech company in 1985, and never made another game.

Softporn itself would find resurrection in the festive graphical world of Sierra’s Leisure Suit Larry series, first released in 1987. The game’s designer, Al Lowe, added character and color, dialog and description, but Leisure Suit Larry is, almost puzzle for puzzle, Softporn. Leisure Suit Larry spawned six games total under Sierra’s wing and several remakes, “unofficial” sequels, and fan reboots. It is a property that has aged poorly into the 21st century though, repeating the same predictable puns and juvenile obsessions. Benton never designed the game to last.

In some sense, Softporn is least interesting as a game, and most interesting as a piece of social theater. While Softporn seemingly affirms every long-suffering trope gaming has to offer—its latent misogyny, its middling cultural stakes, its limp internal humor—it was also developed under shifting social and spatial constraints within an emerging populist computer culture. Softporn flexed a predictable, uninspired muscle against disorienting technological and social circumstances that we long ago forgot were ever disorienting. No one much knew what to do with microcomputers when they lugged them into a garage, basement, or kitchen. Their uses were always equal parts technological utopia and domestic banality (hence the early 1980s fondness for digital recipe organizers). The debate and uproar hounding Softporn’s distribution and reception illuminates corners of computer history left dark by the presumptive wisdom that modern computing fell from the tree of Adam.