Two years after giving away the baby boy she'd carried for nine months, Gao cries less. His new mum treats him well, and she finds comfort in the smiling family photos uploaded online. Besides, she has her own biological seven-year-old to care for – and she's busy searching for another infertile couple seeking a womb.

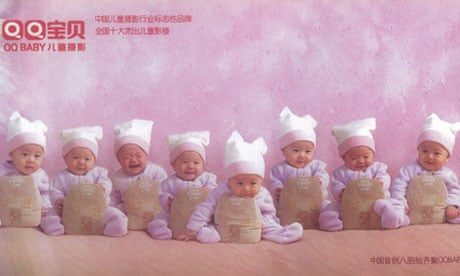

Gao is one of China's surrogate mothers working underground for vast sums of money to deliver children to wannabe parents. The "rent a womb" industry, which inhabits a legal grey area, came under fire in December when it emerged a wealthy couple in the southern city of Guangzhou paid nearly 1m yuan (£100,000) to have eight babies simultaneously, using two surrogates. For a country that limits families to one child, the babaotai chuanwen or "eight baby scandal" – unearthed when the babies' portrait was used to advertise a photography studio – made national headlines.

As China enters the year of the dragon, the surrogate industry is preparing for an upswing in business with parents rushing to have a baby in the luckiest lunar year.

Shanghai authorities expect 180,000 babies to be born in 2012, 10% more than last year, according to the Shanghai population and planning commission. Countries with a strong Chinese diaspora typically experience a boom in "dragon" babies, as the creature is associated with might, intelligence and is historically linked to emperors.

Gao, who didn't want to give her real name, also feels a sense of urgency. "I hope I can find the next client before March, as I'm already 32 and the time left for me [to be a surrogate] is limited," she says. Like many surrogates Gao is from one of China's remote regions, in her case the most north-eastern province, Heilongjiang.

Two years ago she received 200,000 yuan (£20,000) for her services to an infertile, middle-aged couple from the affluent former capital, Nanjing. Surrogates can earn anything from 100,000 yuan to over 300,000 yuan, approximately 120 times the average monthly salary of a graduate in Beijing. Though there is no specific law relating to surrogacy in China, in 2001 the industry was driven underground when the ministry of health banned trade in fertilised eggs and embryos, forbidding hospitals from performing surrogacy procedures.

Regulations are openly flouted. While there's no official count, the Guangzhou-based newspaper Southern Metropolis Weekly estimated last year that there have been 25,000 surrogate children born in China in the past 30 years. More than 100 surrogacy agencies advertise online.

Given that 10% of couples struggle with infertility, a rate that is on the rise according to research by the ministry of health, there's a potentially huge market for surrogacy in China. "Parents living in Shanghai or Beijing have to travel to far-flung cities such as Wuhan, Harbin and Hohhot to meet a surrogate mother and find a hospital willing to finish the transplantation," says Mrs Zhou, a surrogacy agent in Shanghai, who requested just her family name be used. Most couple-surrogate pairings are arranged through internet-based agencies, with agents expected to find one or two surrogates each month, earning 2,000 yuan (£200) for each, according to Zhou.

During pregnancy, surrogates are often contractually obliged to reside in a "surrogate dorm", where they share rooms, are cared for by nannies and are governed by a strict set of rules. At Zhou's agency, violations include being awake after 9.30pm and telling friends and relatives the dorm's whereabouts. Surrogates who flout the rules are subject to a fine (typically 500 yuan or £50) and may lose their end of the contract.

Many infertile parents are willing to pay any price for a precious single child. "You suffer psychological torture from the fear you will never have a child," says Mr Li, 42, a father whose child was born through a surrogate and who requested his name be changed. "Then you fear that something will happen when the surrogate mother is pregnant, and then, even when you have the child in your arms, you begin to worry that someone will discover the truth."

Li, a wealthy businessman who owns a chain of restaurants in Chengdu, already has a seven-year-old daughter but is planning to have a dragon boy this year.

Though the ministry of health stipulates that the use of reproduction techniques such as IVF must conform to China's "family planning policy", surrogacy is one way moneyed parents bypass the one-child rule. "There are some parents trying to avoid one-child policy by surrogacy, but I think the practice should be governed by some laws or rules," says Zhai Zhenwu, director of Renmin University's school of sociology and population.

"It's unfair to poor citizens to whom it seems the rich can have as many children as they want. It's another negative signal to society that money can buy anything, when we should be teaching people that the golden key can't open every door."

But for women such as Gao, the decision to surrogate isn't an ethical one: it provides her family with much-needed cash, even if there's an emotional cost. Though her husband cared for her in their home during her first surrogacy, for the next Gao plans to move out of town. "My relatives and neighbours would be sceptical if I tell them the baby is stillborn again," she says.

Additional reporting by Xia Keyu.