Everything about Marlon Brando was big: his talent; his neuroses; his sexual appetites; and, notoriously, in his later years, his waistline. But perhaps the most outsized aspect of Brando, who died in 2004 aged 80, was the myths that swirled around him.

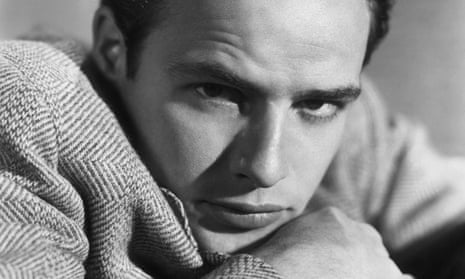

No actor has ever made such a visceral, game-changing entry into films as Brando did in the 1950s – and none, probably, ever will. He had studied with the renowned acting coach Stella Adler in New York, using the Stanislavsky system. Though he disliked the term “method”, his instinctive, unpredictable performances were in radical contrast to the mannered style of the time.

He arrived, muscular and beautiful, reprising a role he had played in the theatre: Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). Williams would later describe him as “the greatest living actor… greater than Olivier”. He was nominated for an Academy Award and it began an extraordinary streak: Viva Zapata!, which led to another best actor nomination, The Wild One and, in 1954, On the Waterfront, his first Oscar win.

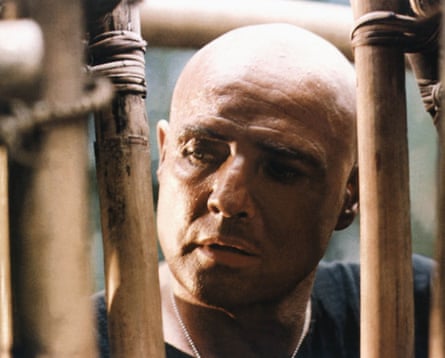

Brando may not have achieved such consistency throughout his career, but he assured his iconic status with later performances as Don Corleone in The Godfather (1972), his second Oscar, Last Tango in Paris and, most controversially, his turn as the unhinged Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now in 1979. The director Martin Scorsese believes that acting has to be divided into “before Brando” and “after Brando”.

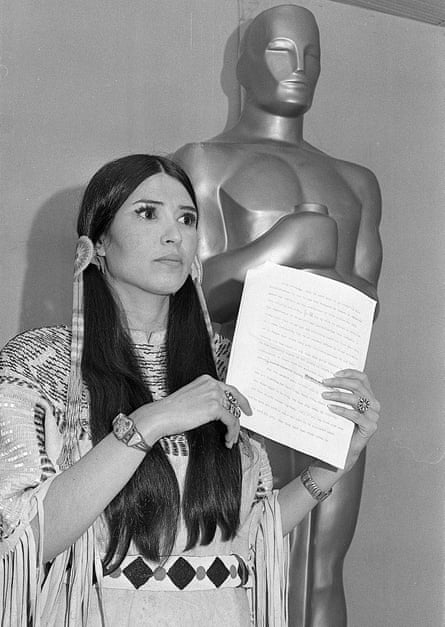

Off screen for much of his long career, Brando distrusted the press and lived reclusively. He was an environmentalist – buying Tetiaroa, an atoll north of Tahiti, in the 1960s and pledging to protect it – and a social activist long before it was commonplace in Hollywood to support such causes. His decision to send Sacheen Littlefeather, a Native American, to decline his Oscar for The Godfather was pilloried as much as it was praised. As a result of Brando’s withdrawal from the public eye, an impression of the man began to calcify from those intense early screen roles. The stories that escaped from film sets only encouraged more frenzied speculation: he had a volcanic temper, he was impossible to direct, he was having an affair with Jack Nicholson...

What we did know of Brando’s private life was pure soap opera. He had three wives and more than 11 children, most biological, some adopted. In 1990, his eldest son, Christian, shot the boyfriend of his half-sister, Cheyenne, and wound up in prison. Five years later, Cheyenne hanged herself, leading the media to call Brando’s Beverly Hills mansion “the House of Pain”.

Brando rarely spoke out – until now. A compelling, often surprising new documentary, Listen to Me Marlon, tells his life story in his own words. The narration comes from more than 200 hours of personal audio tapes made by Brando, starting in the 1950s and continuing for the next 50 years. The images that accompany the recordings are movie clips, archive interviews and an unsettling, digitised 3D rendering of Brando’s head that he was measured for in the 1980s. The film reveals a Brando we have not seen before: a voracious autodidact, self-doubting, often misinterpreted. As his voice rumbles on, it’s hard not to feel that he is setting the record straight from beyond the grave.

The film features no outside interviewees, no talking heads. So, for the New Review, we have brought together a group of people able to elaborate on and contextualise Brando’s narrative. From the family, there’s Miko Brando and Rebecca Brando, the two children he had with his second wife, Movita Castaneda, a Mexican-American actress in the early 1960s. Rebecca is now a clinical psychologist and Miko has worked for more than 30 years for the Michael Jackson estate, first as Jackson’s bodyguard and assistant and, since his death, cataloguing the musician’s possessions. The British makers of the film, director Stevan Riley (Blue Blood) and producer John Battsek, whose credits include Oscar-winning documentaries One Day in September and Searching for Sugar Man, also offer their experiences of uncovering the unknown Brando.

*****

Brando had a fascination with technology and recorded himself for a number of reasons: to provide creative notes on roles he was preparing for, or for meetings with Hollywood executives – whom clearly he didn’t trust – or as a reminder of unfamiliar vocabulary he’d come across or thoughts he had picked up from his library of more than 4,000 books.

Rebecca Brando: I didn’t know the tapes existed. I’d see him talk into the dictaphone sometimes, but he would stop as soon as he saw me and say, “Hi, darling, how are you?” He’d put it away and I just thought, “Oh, he’s memorising lines or preparing something for work.” But I hadn’t known there were hundreds of hours of audio tapes from over the years. So for a very long time, maybe somewhere in the back of his mind, he knew that these tapes would become of some use.

John Battsek: We met with the Brando estate and the family and they said: “We have this treasure trove of an archive, which you are welcome to delve into to whatever extent you want.” They opened the doors to it and then had no involvement of any sort for the best part of 18 months as we made this film – other than to supply us with more and more material as we requested it.

RB: Making these tapes, I think, was a way to self-analyse. My dad loved to talk to people and he would call people in the middle of the night and talk about anything and everything, about life, nature, business and inventions. So when people weren’t available, he would talk into these dictaphones.

Stevan Riley: I feel a bit silly, because this only came to me late on, but I think Brando liked the tapes because he was dyslexic. His spelling was pretty bad – he would write a lot in the margins of books he was reading – so I wonder if he preferred speaking to writing.

RB: He didn’t talk about his personal life to us children ever. So a lot of it was just a therapeutic way to find some kind of truth. On the tapes, he’d talk about his mother and his father and his family and his growing up – he wanted to figure out the way things had developed in his life from his childhood.

*****

Brando appears to have been profoundly scarred by his early years. Both his parents – his father, Marlon Sr, a pesticide manufacturer, and mother, Dodie, an actress – were alcoholics; his father could be violent. Brando was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1924, but the family moved around a lot: his parents separated and then got back together, and Marlon Jr drifted until he discovered acting himself after being sent to a military academy. He was convinced for much of his life that nothing he would do with his life would ever please or engage his father.

Stevan Riley: I read a quote that Brando didn’t like Freud, but everything he was doing was very Freudian. It’s fascinating that when he set up his own independent production company he called it Pennebaker – his mum’s maiden name. And when he signed a six-film deal with Universal to make films, he appointed his dad as head of business affairs at Pennebaker to control the money. So I think he was subconsciously after his dad’s approval – just as we are all after our parents’ approval and recognition – and that wasn’t reconciled within himself. He couldn’t stand his dad and yet he desperately wanted his approval – that’s how complex it was.

Rebecca Brando: I didn’t know my grandparents and he rarely talked to me about them. But, towards the end, he expressed how your parents are only going to do as good as they can with the tools they have. And you can’t blame your parents for their shortcomings. So I know he tried to be a better parent than his parents were to him. As much as he had so many children, he tried to be present for them, by bringing us together, going away on trips, making sure we had dinners together.

SR: We found these self-hypnosis tapes; Brando would do regressive hypnosis to access his youth. He was trying to find quiet, peaceful moments before the chaos hit the household. He loved watching the BBC’s The Singing Detective, with Michael Gambon, and he always felt he was the boy in the tree. He said that was him. And he would hark back to this elm tree, which he’d climb and find peace and solitude.

Miko Brando: He never spoke bad about his parents to us or put them down. And he’d always say to me, “Miko, you learn by your mistakes.” I guess what I’m trying to say is that he never made us feel the way supposedly his father did him. He always made us feel number one and happy and cherished. Loved.

SR: He adored his mother, and held her up as this angelic figure, forgave a lot of her neglect of him. And he expected women to be these angelic figures who might save him. But I think he had to confront that notion because he recognised that his mum was never an angel and his mum wasn’t there for him. And yet, he was desperate for a family and that’s probably why he tried to form such a big family of his own: he missed that family life desperately as a kid and he sought to recreate it.

*****

“I was young and destined to spread my seed far and wide,” says Brando in Listen to Me Marlon. He fathered at least 11 children, possibly many more; he had three wives and innumerable affairs with both women and men.

Stevan Riley: One of the questions I’d ask people was: “Who was the love of his life? Was Marlon a romantic? Or was he this opportunist womaniser?” And, as ever with Marlon, there was always this ambivalence: he was deeply romantic but his relationships with women were crippled by his early experiences. As he says in the film, he had an abandonment complex with women. He was incredibly jealous by his own admission. Who’d have thought that a sex symbol, who was so eligible as Brando at his peak, would be so vulnerable?

Rebecca Brando: I know he had a distant relationship with my mother, Movita, after they separated. She was a very prideful woman, she was no-nonsense, so in the early part of my life they didn’t have a close relationship. But towards the end of his life they had a friendship: they laughed together and flirted together and had some nice times. I know he always maintained a close relationship with Tarita, his Tahitian wife. Anna Kashfi, his first wife, was different. They didn’t have a close relationship.

SR: He was very distrustful. Especially when fame hit, he was even more suspicious that people wouldn’t want him for himself and who that person was: the young boy in Nebraska. He used to separate – and his family would separate – between Marlon and Bud. Bud was the nickname he had when he was a kid and they were almost two personas: Marlon Brando the movie star, and Bud Brando, his true self. And he didn’t really feel that anyone – in particular women – really wanted to know Buddy Brando. All they wanted was Marlon Brando, the movie star, so he tried to dismantle relationships.

John Battsek: He says it himself: he wasn’t a good enough father. I feel he was very self-aware, and he went to a thousand therapists, and yet he just couldn’t stop himself from acting out his failings and doing it repeatedly.

RB: My dad wasn’t perfect: he could be moody and distant, but for the most part he was fun and funny. He had such a presence, even his silence was just impactful. You always wanted to know what he was thinking because he was just so charismatic and magnetic – even to his own children. You just wanted to be with him all the time. And I’m not saying that because I’m his daughter; I’m saying it because it’s true! Many people did not get enough of his time and he only had so much time to give everyone and it was never enough.

Miko Brando: He was a loving, caring, funny father and just a good person to be with. When we were around him, he wasn’t Marlon Brando, the famous, two-time Oscar winner, legend actor. He was just Dad, and you played around with him, you wrestled with him and told jokes. So yeah, my recollection is of good times – I sleep very well at night.

*****

That Brando is one of the all-time great film actors is impossible to dispute. As Jack Nicholson said, “When Marlon dies, everyone moves up one.” However, in later years especially, Brando’s reputation received some dents. For Apocalypse Now – for which he was paid $1m for three weeks’ work – the director, Francis Ford Coppola, complained that he arrived overweight and not even having read the book, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, that inspired the film.

Stevan Riley: From the tapes it became obvious that Brando did really extensive creative notes around parts he was preparing for. It’s interesting because everyone thought he was a seat-of-your-pants, ill-prepared actor, but I found he was anything but. He was a quiet perfectionist in that sense.

Rebecca Brando: I went to Tahiti a couple of weeks ago and I went to one of the islets I’d never been to before. I was telling my brother Teihotu and he said: “That’s funny, that’s where Dad went to prepare for Apocalypse Now. He lived there for two months.” There’s no plumbing, no electricity, it’s surrounded by this very jungle-like bush; it was a kind of simulation for the Vietnamese setting of the film. And then we have Francis Ford Coppola saying he was unprepared… As my dad says in the documentary: “He threw me under the bus. In fact, I saved his film.”

SR: When Marlon was talking about acting, he’d say that your brain is your enemy. The first thing you must do is shut off your brain and just focus on feeling. It was about accessing emotions from the past for the character, which according to the method would involve you delving into your own past as well. Then, once you’d accessed the character emotionally, you’d bring your brain back in and figure out all the character’s mannerisms. The small details about what they eat, whether they’ve got fluff on their jumper they pick off on a regular basis – just tiny details you could stack, stack, stack so that they were there in your subconscious mind and you could then ditch them when the director said “Action!”

John Battsek: This is the only film I’ve made where every week I would get a call saying that one of the 30 most famous actors in the world would like to see the film, how can that be arranged? Every week someone contacts us: “Can Warren see the film?” “Can Jack see the film?” “Can Jake see the film?” It’s non-stop. “Can Dustin see the film?”

RB: He never encouraged us to be actors. He thought acting was just completely unrealistic and you’re in the illusion that you are this grand person and why? Because you’re an actor? It didn’t make sense to him. He thought that people who were educated and who made a difference in this world were the ones who should be getting paid millions of dollars: the Nobel prizewinners, the scientists, the teachers, the doctors.

Miko Brando: He called it the “bullshit life” of Hollywood people. He never came home in character. I went to France with him when he was shooting Last Tango. Did I know the movie he was making at the time? No. Did I care? No. I just knew he was going to work, it was very simple.

After avoiding the spotlight for years, Brando was dragged into it in 1990 when his eldest son, Christian, shot and killed Dag Drollet, the boyfriend of Christian’s half-sister Cheyenne. The incident took place in Brando’s home in Beverly Hills and, after a very public trial in which Brando was a key witness, it led to Christian – who claimed he was drunk and had shot Drollet accidentally – being sentenced to 10 years in prison for manslaughter. Further tragedy followed in 1995 when Cheyenne, aged 25, took her own life by hanging herself. Christian died in 2008 from pneumonia.

Miko Brando: I was with my dad every day in court; we’d travel every day to and from the courthouse. It weighed on us a lot, it was tough living those few months that way. It happened at his house. It was his daughter’s boyfriend; he was a very nice gentleman, he was part of the family. It’s an incident I don’t think any family wants to go through. You see it on TV a lot, but you don’t think it’s going to happen to you.

Rebecca Brando: My father was greatly grieved and saddened and he was unable to talk about any of it. So the fact that he couldn’t talk about it meant we couldn’t reach him.

Stevan Riley: As a child, Christian was part of a very destructive custody battle with Anna, Marlon’s first wife. He was definitely piggy in the middle and it can’t have been a good environment for him to be brought up in. Marlon wasn’t ignorant to this fact because of all the stuff he was analysing in his own life. So I think he just put two and two together and in the end it becomes a bit of a dynastic tale: are we condemned to make the mistakes of our parents? He was very interested in that quote: “Give me a child until he’s seven and I will show you the man.” And I think he understood that those formative years are all-important and reverberate through the rest of your life.

John Battsek: We were very straight up about the fact that we wanted the film to touch on as many of the complexities of the man as possible and that would include some uncomfortable stuff, including his womanising, including the stories of his behaviour on set, including what happened to his kids.

SR: Marlon said once, “If only we could live to 150…” It’s that idea that youth is wasted on the young. And he said it had taken 70 years to repair the self-destructive tendencies rooted in his youth. But Marlon was a survivor. Remember, he outlived everyone in his generation: Montgomery Clift, Marilyn, James Dean. He stuck it through to the bitter end and he didn’t want to give up. But if ever he was on the verge of giving up it would have been after Cheyenne’s death.

*****

For such a reluctant public figure, all concerned fretted about how Brando would have felt about Listen to Me Marlon being compiled from his private archive. Some comfort came from the fact that, in the tapes, he talks about collating material for his own documentary one day.

Miko Brando: This film is about as close as you get to knowing him without ever meeting him.

Rebecca Brando: The first time I saw it, I had to walk out of the theatre. Then we had a screening for family members and there were tears from some parts but also a lot of pride, because it does set the record straight. And hopefully it corrects the misrepresentation done by the press. So there was a quietness afterwards, people were quietly content.

John Battsek: Imagine if Rebecca Brando had turned round and said, “What the fuck is that? That’s not my dad.” That would have been just be too horrendous.

Stevan Riley: He talked about reaching a point of peace and understanding. You hear him at the very end say, “These tapes are no longer useful, chuck ’em.” He thought the system had worked and the healing had some positive effect. I like to retain a bit of that thought.

Listen to Me Marlon is in cinemas 23 October, on digital HD 9 November, and on DVD and Blu-ray 30 November

The odd couple: Marlon Brando and Michael Jackson

As unexpected friendships go, Marlon Brando and Michael Jackson’s takes some unravelling. The pair met through Brando’s son Miko, who began working as Jackson’s bodyguard in the 1980s and is still employed by his estate.

Miko Brando: They were very close. Anything my father needed in the last few years of his life, Michael was there. My father didn’t have a TV in his bedroom at the time and Michael and I would come and visit him, sit on his bed and talk to Dad, and my dad would leave the room for a second and Michael would say [whispers], “Miko, your dad doesn’t have a TV in his bedroom.” And I said, “Yeah, if he wants to watch TV he goes into the other room, but he basically studies and relaxes in here, and reads and writes, he does his own thing.” And he said, “No, we’ve got to get him a TV in here.” Sure enough, next day, Marlon Brando had a TV in his bedroom, courtesy of Michael Jackson.

Stevan Riley: One of the very first tapes I listened to was a long conversation between Michael and Marlon. I think it was early in their relationship because it felt like they were testing the waters with each other and explaining themselves. But Michael was thinking about becoming an actor and had gone to see Marlon about taking lessons.

MB: The last time my father left his house before passing away, he spent about a month and a half up in Michael’s ranch, Neverland Valley. Just hung out. Michael got him his own chef, his own butler, his own housekeeping. His own rooms. He got him his own golf cart so he could roam around Neverland at his leisure and enjoy the flowers and the trees and the scenery and the tranquillity. You couldn’t get any closer at the end than those two.

SR: There were similarities: they were obviously both under the media spotlight, they were both imprisoned by celebrity. But Brando was arguably more adult. He sensed a vulnerable soul in Michael and there was a degree of empathy and nurturing going on. He had an interesting impulse to adopt and be a father figure to people. A lot of his children were adopted. And oddly enough, I saw some letters from Jackson to Brando, where he was calling Brando “Dad”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion