/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/35011021/450883216.0.jpg)

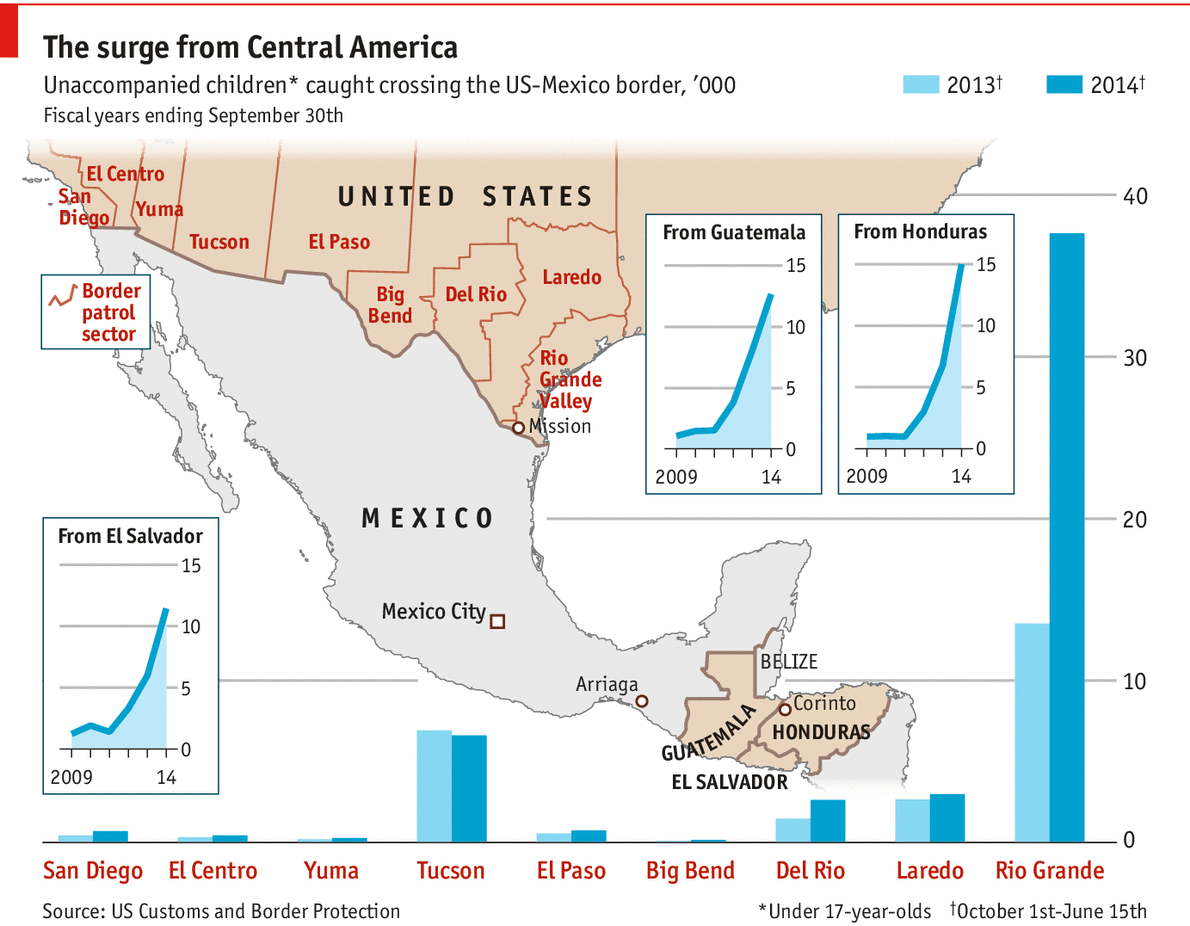

A surge of unaccompanied child migrants has been crossing the US-Mexico border and seeking refuge in the United States since 2011, and the problem seems to be getting worse. US Customs and Border Protection says that apprehensions of unaccompanied children are up a staggering 92 percent from the previous year, with growing numbers of children coming from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Since October, 52,000 children have come to the US without an adult.

They're coming in so quickly that normal immigration facilities have been completely overwhelmed, and thousands of kids are now being warehoused in makeshift detention centers, like the one shown above. Border state politicians, particularly Republicans, want to tighten immigration restrictions; immigrant rights activists say that's the exact opposite of what these children need.

Recent studies suggest that most of these unaccompanied children aren't economic migrants, as many Americans might assume — they're fleeing from threats and violence in their home countries, where things have gotten so bad that many families believe that they have no choice but to send their children on the long, dangerous journey north. They're not here to take advantage of American social services — they're refugees from conflict. Understanding the nature of the violence pushing them north is crucial for figuring out what to do about the child refugee crisis on our southern border.

Why are so many children fleeing Central America?

Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, the three countries that make up Central America's "Northern Triangle," are experiencing a terrifying level of violence that's been rising rapidly since the late 2000s. State weakness and corruption have allowed a number of different armed groups — including transnational street gangs, drug cartels, and other organized crime syndicates — to flourish, checked by little but their competition with one another.

Today, those groups battle for control of drug trafficking routes, residential neighborhoods, bus systems, human-smuggling operations, and more or less anything else that allows them to leverage their skills in violence to extract a profit.

To put the problem in perspective, this chart shows murder rates in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras since 2007:

And this chart shows civilian casualties in Iraq from the same period:

Source: UNODC

These charts show that the murder rate in Honduras in 2012 was a whopping 30 percent higher than UN estimates of the civilian casualty rate at the height of the Iraq war. In other words, all three Central American countries were, statistically speaking, twice as dangerous for civilians as Iraq was.

Why are children coming in such large numbers? Are gangs targeting kids specifically?

Children are uniquely vulnerable to gang violence. The street gangs known as "maras" — M-18 and Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13 — target kids for forced recruitment, usually in their early teenage years, but sometimes as young as kindergarten. They also forcibly recruit girls as "girlfriends," a euphemistic term for a non-consensual relationship that involves rape by one or more gang members.

If children defy the gang's authority by refusing its demands, the punishment is harsh: rape, kidnapping, and murder are common forms of retaliation. Even attending school can be tremendously dangerous, because gangs often target schools as recruitment sites and children may have to pass through different gangs' territories, or ride on gang-controlled buses, during their daily commutes.

A recent report on the child migrant crisis from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) includes testimony from several children who came to the US to escape gang violence. Here's 17-year-old Alfonso, explaining why he fled after receiving threats from Mara-18 members at his school:

"The problem was that where I studied there were lots of M-18 gang members, and where I lived was under control of the other gang, the MS-13. The M-18 gang thought I belonged to the MS-13. They had killed the two police officers who protected our school. They waited for me outside the school. It was a Friday, the week before Easter, and I was headed home. The gang told me that if I returned to school, I wouldn't make it home alive. The gang had killed two kids I went to school with, and I thought I might be the next one. After that, I couldn't even leave my neighborhood. They prohibited me. I know someone whom the gangs threatened this way. He didn't take their threats seriously. They killed him in the park. He was wearing his school uniform. If I hadn't had these problems, I wouldn't have come here."

15-year-old Maritza:

"I am here because the gang threatened me. One of them "liked" me. Another gang member told my uncle that he should get me out of there because the guy who liked me was going to do me harm. In El Salvador they take young girls, rape them and throw them in plastic bags. My uncle told me it wasn't safe for me to stay there. They told him that on April 3, and I left on April 7. They said if I was still there on April 8, they would grab me, and I didn't know what would happen."

17-year-old Mario:

"I left because I had problems with the gangs. They hung out by a field that I had to pass to get to school. They said if I didn't join them, they would kill me. I have many friends who were killed or disappeared because they refused to join the gang. I told the gang I didn't want to. Their life is only death and jail, and I didn't want that for myself. I want a future."

As these testimonies show, merely attempting to get an education can be life-threateningly dangerous for children in gang-controlled areas — which helps to explain why so many feel they have no choice but to leave.

What about the police? Can't they protect the kids?

Members of the Mara 18 gang on trial for extortion and murder in Guatemala City. JOHAN ORDONEZ/AFP/Getty Images

Nope. In all three countries, the police are too weak and corrupt to offer any meaningful protection. In fact, the police often essentially operate as dangerous criminal gangs themselves.

In both El Salvador and Honduras, there are numerous, credible reports that the police are responsible for hundreds of "social cleansing" killings, including the murders of youths they suspect to be gang members. The Salvadoran national police "specializ[es] in obstructing justice and guaranteeing impunity for those with sufficient amounts of money," writes Hector Silva, a fellow at American University who researches police corruption.

Guatemala's police (and military) were so thoroughly infiltrated by organized crime that in 2006 the United Nations had to set up a special agency, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (which goes by its Spanish acronym, CICIG), to help fight the pervasive abuses committed by "clandestine groups." CICIG has enjoyed some recent successes, but nearly three in four killings committed in Guatemala still go unpunished.

But isn't the journey to the US also dangerous for children?

Yes, it is — but for desperate families trying to save their kids' lives, it's often the best of a bad set of options.

There is no denying that the long overland journey from the northern triangle to the US is tremendously dangerous. Routes north are increasingly under the control of Mexico's Los Zetas cartel, according to a recent report from the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, which means that child migrants are at risk of "violence, extortion, kidnapping, sexual assault, trafficking and murder" during the journey. Sending a child to the United States is also extremely expensive. "Coyotes" (people smugglers) charge $5,000 to $7,000 to bring a child to the US, according to the same report — an amount that can represent more than 18 months of earnings for an entire family.

Still, even with all the dangers of the journey north, when children become the targets of gang threats, there is often no better option available to their families than to send them to the United States (or another safe country). Refusing the gang's demands is more dangerous, because it is likely to lead to violent retaliation. Agreeing to join a gang is more dangerous, because it means signing up for a (probably short) life of crime and violence. Acceding to a gang member's sexual demands is more dangerous, because it means accepting certain rape, as well as the other dangers that come from being associated with a criminal group. Because the police do not offer meaningful protection, migration is the only course of action that remains.

Coming to the US is risky. But for these vulnerable kids, it's the best hope there is.

What can the US do about this crisis?

Children detained at the US immigration holding center in Nogales, Arizona. Ross D. Franklin-Pool/Getty Images

Part of the challenge for the US is reducing the number of children who arrive at the border in the first place. The most effective way to do that would probably be to allow kids to apply for asylum (or another form of humanitarian immigration relief) from their home countries.

That policy would allow children to escape violence at home without forcing them to risk the dangerous overland journey. It would also ease the burden on US immigration facilities, because there would be no need for the children to be detained after entry, or to go through removal proceedings in immigration court. Unfortunately, that option does not appear to be under serious consideration.

The other part of the challenge is what to do about the kids who are already at the border. For this, President Obama is asking Congress for additional authority to deport unaccompanied children quickly. It's likely that that would mean sending them back after just a brief interview with border guards, without a full hearing on their asylum claims or an opportunity to request other humanitarian relief. If that happens, it is all but certain that some children with legitimate fears of persecution will be sent back to their home countries, either because they are too young and unsophisticated to advocate for themselves, or because they are too afraid to tell interviewers the whole story right away.

As those policies are debated in the coming days, it's important to remember what Obama is really proposing: to send young children back, alone, to a conflict zone that is twice as dangerous as Iraq was from 2008 to 2012.