How the FBI Tried to Block Martin Luther King’s Commencement Speech

The untold story of a government plot, a maverick college president, and the most important figure of the civil rights era

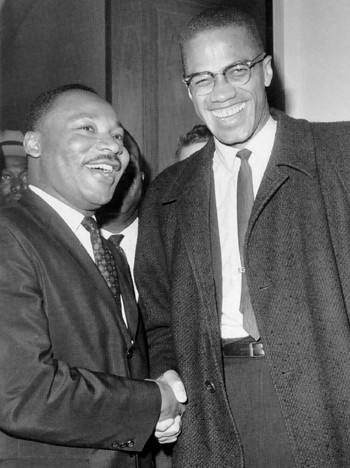

Their one and only meeting lasted barely a minute. On March 26, 1964, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X came to Washington to observe the beginning of the Senate debate on the Civil Rights Act. They shook hands. They smiled for the cameras. As they parted, Malcolm said jokingly, “Now you’re going to get investigated.”

That, of course, was well underway. Ever since Attorney General Robert Kennedy had approved FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s request in October 1963, King had been the target of extraordinary wiretapping sanctioned by his own government. By this point, five months later, the taps were overflowing with data from King’s home, his office, and the hotel rooms where he stayed.

The data the FBI mined—initially about King’s associations with Communists and later about his sexual life—was used in an attempt to, depending on your point of view, protect the country or destroy the civil rights leader. Hoover and his associates tried to get “highlights” to the press, the president, even Pope Paul VI. So pervasive was this effort that it extended all the way to the small campus in Western Massachusetts, Springfield College, where I have taught journalism for the past 15 years.

In early 1964, King was invited by Springfield President Glenn Olds to receive an honorary degree and deliver the commencement address on June 14. But just days after King accepted the invitation, the FBI tried to get the college to rescind it. The Bureau asked Massachusetts Senator Leverett Saltonstall, a corporator of Springfield College, to lean on Olds to “uninvite” King, based on damning details from the wiretap.

King’s biographers have recorded little about this episode. Neither David Garrow nor Taylor Branch—who both won Pulitzers for books about King—ever mentioned Glenn Olds by name or title. Saltonstall is relegated to a one-sentence footnote in Garrow’s The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr., a groundbreaking 1981 book that unmasked the Bureau’s extensive surveillance of the civil rights leader. In the hardcover edition of Branch’s 2006 book, At Canaan’s Edge, the third volume of a towering trilogy about America in the King years that took more than two decades to create, the renowned historian wrote that Saltonstall had “helped block an honorary degree at Springfield College, by spreading the FBI’s clandestine allegations that King was a philandering, subversive fraud.”

There was just one problem with this lively statement. Nobody blocked an honorary degree for Martin Luther King at Springfield College.

It was a small lapse by a formidable researcher and masterful storyteller. But lurking beneath this mistake is a great and almost entirely untold story about the most important figure of the civil rights era and a maverick college president facing his moment of truth.

The students in Springfield’s class of 1964 lived a Forrest Gump-like connection with U.S. history. Born just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, they came to college at the dawn of a new decade. In the fall of their freshman year, Massachusetts’ native son John F. Kennedy appeared at a rally in downtown Springfield one day, and got elected president of the United States the next. In the fall of their senior year, they flocked to the few black-and-white televisions on campus to join America’s grim vigil when JFK was shot. The following June, they expected to turn their tassels from right to left in the presence of Martin Luther King.

For most of their college days, there was an innocence to this group of American youth, at a time just before the ’60s became The Sixties. During their freshman year, they wore beanies. Their social worlds included hootenannies, panty raids, and carefully regulated visiting hours in single-sex dorms, with strict rules of “doors open, feet on the floor.” Many students of the almost exclusively white class learned The Twist from Barry Brooks, a popular “Negro” student from Washington, D.C., who earned election to the Campus Activities Board.

These students, at the tail end of the so-called “Silent Generation,” were less inclined to question authority or conventional wisdom than their younger siblings would later be. They’d also chosen to attend Springfield College, an old YMCA school, known as the birthplace of basketball and best regarded at the time for producing wholesome teachers of physical education. “It was,” says Barry Brooks, “sort of an apple pie kind of place.”

Members of the class were only vaguely familiar with Glenn Olds, who served as college president from 1958 to 1965. He was a trim and conservatively dressed man with receding blond hair and an engaging grin. He sometimes hosted groups of students at his on-campus house, serving apples, cheese, and water. He never drank alcohol or caffeine. He began each morning with calisthenics.

But there was nothing drab about him. Olds was a man marked by dazzling dualities. Raised by a Mormon mother and a Catholic father, he became a Methodist minister. Working from a young age as a logger and a ranch hand, he went on to get a Ph.D. from Yale, penning his dissertation on “The Nature of Moral Insight.” While at Springfield, he maintained an office in Washington, working on progressive programs for Democratic presidents—the Peace Corps for Kennedy and VISTA for Johnson—but later worked full-time for Nixon (and even later got fired by him). He was married three times and divorced twice—all to Eva Belle Spelts, a former “Ak-Sar-Ben Princess” from Nebraska. They are buried together on a mountainside in Oregon.

Glenn Olds would later go on to take over the presidency at Kent State in 1971, the year after National Guardsmen shot and killed four students who were protesting the Vietnam War. In 1986, without any experience as a political candidate, he would run as a Democrat for U.S. Senate from the state of Alaska, getting 45 percent of the vote, but losing to incumbent Frank Murkowski, whose daughter holds the seat to this day.

Olds could be an intimidating man. As a youngster in Oregon, he made money for his family by starring in “curtain raisers” at boxing matches. According to his son, Dick Olds, the founding dean of the UC-Riverside Medical School, Glenn never lost his swing. “I still remember vividly an event that occurred at Springfield College,” says Dick, who lived on campus from age 8 to 15. “There was a drunk guy in the student union. He was yelling stuff and knocking some things on the ground. My father went over to talk to him and tell him that he needed to leave. The guy took a swing at my dad. My dad knocked him out, down on the floor, one punch. I’d never seen anything like that.”

But Glenn Olds was also an ardent pacifist. As a senior at Willamette University, he stood with other clergy on the night of the Pearl Harbor attack, preventing marauders from charging into a Japanese-American farming enclave at Lake Labish. He sought religious exemption from the war as a conscientious objector—even as both of his brothers fought, one of them coming home wounded from Okinawa. In 2004, two years before his death, Olds told me that he had been disowned by his father, Glenn Olds Sr.: “He’d rather see a son of his dead than refuse to put on the uniform.” That did not dissuade him. “I took the pacifist position to be essentially the one Jesus took,” Olds said. “I thought I was on good historic ground.”

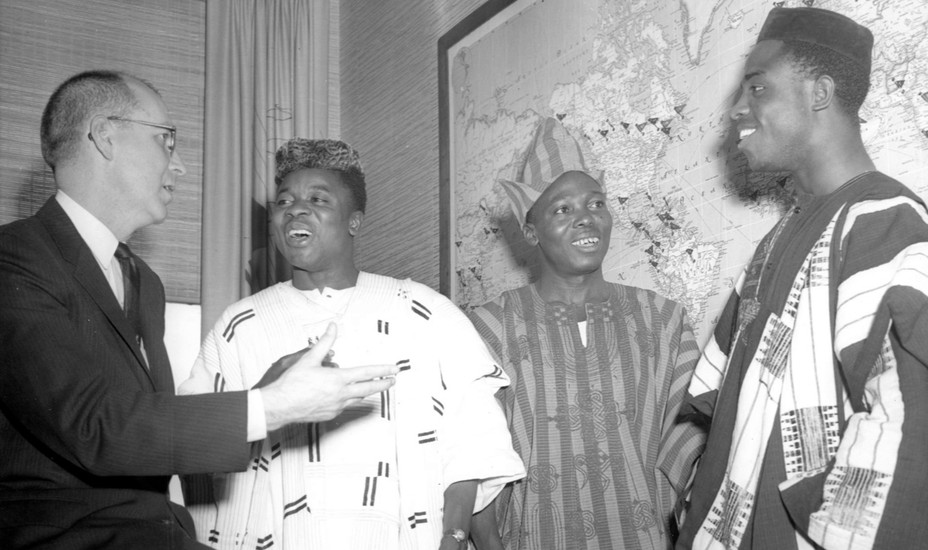

During summers, Olds offered the Springfield campus as a site for Peace Corps training. At the 75th anniversary of the college in 1960, he brought in speakers who were renowned pacifists: Aldous Huxley, Margaret Mead, and Norman Cousins. So it was no real surprise when he sought out Martin Luther King as a commencement speaker in 1964.

By this point, King had been established as a paragon of pacifism, and his movement had started to gain national traction. Just a year before, in the spring of 1963, the fire hoses and gnashing dogs of Bull Connor’s Birmingham, juxtaposed with the quiet dignity of black children and teenagers, had awakened much of America to the brutality of racism. A few months later, on a hot day in late August, the March on Washington had not devolved into a blood bath as some leaders feared. Instead it had become a beacon of peace and unity.

But there was, of course, the backlash. One day after President Kennedy first introduced the Civil Rights Act, Medgar Evers was killed by a white supremacist. And just 18 days after the March on Washington, four young girls in white dresses were murdered by a dynamite blast in a Birmingham church.

Two months after that, Martin Luther King watched the Kennedy assassination from a television in his Atlanta home. Turning to his wife Coretta, he said, “This is what’s going to happen to me. This is such a sick society.”

Glenn Olds had a couple of connections with the civil rights leader. One was through Andrew Young, King’s close friend and a top associate with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Olds had come to know Young at a youth leadership conference and on a Methodist preaching tour. The other connection was through a fellow college president in Massachusetts, Harold Case of Boston University, where King had gotten his doctorate. Olds apparently made his first contact with King in mid-March. A surviving letter in the Springfield College archives from Director of Public Information George Wood is dated March 24, 1964. Addressed to King at his home on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, the letter starts out:

The letter deals with logistical matters and also asks for “a current biography and as many glossy photographs of you as can be spared.”

Two days later, The New York Times reported that Olds and two others had been “named today to develop plans for key parts of the Administration’s anti-poverty program, now pending in Congress.”

That was also the day Malcolm X and King had their chance encounter in Washington. Malcolm was at a crossroads, 18 days after breaking from the Nation of Islam and 18 days before embarking on his pilgrimage to the Mideast. King was at the apex of his fame. He knew that the stakes surrounding the Civil Rights Act were high. All the restraint he had called for, all the belief in the American system, all of his credibility about the arc of the moral universe bending toward justice was invested in the passage of this law, widely regarded as the most important in the 20th century.

He knew it would not be easy. Just four days later, Southern senators launched what would prove to be an epic 10-week filibuster of the bill. Georgia’s Richard Russell publicly proclaimed, “We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our states.”

Far more secretively, just three days after that, the FBI turned its attention to keeping Martin Luther King away from Springfield College.

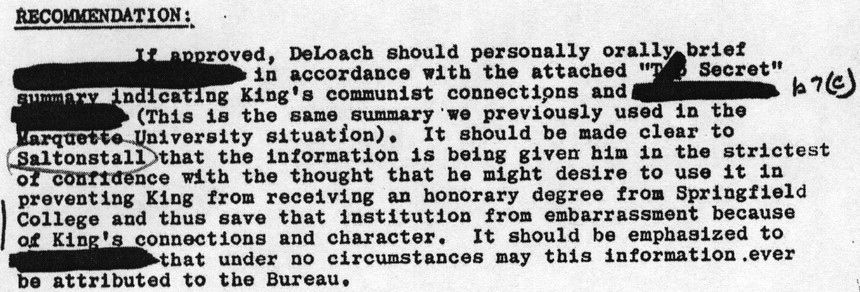

The initial April 2, 1964, memo from F.J. Baumgardner to Head of Domestic Intelligence W.C. Sullivan was heavily redacted when it was declassified years later, but it still spelled out the plan quite clearly. According to Baumgardner, the FBI had learned that both Springfield and Yale were considering King for honorary degrees. He said the Bureau was “initiating appropriate checks as to the availability of such established and reliable sources at these institutions which would permit the heading off of the conferring of honorary degrees to King.” The strategy had already “prevented King from getting an honorary degree from Marquette University.”

Baumgardner said the plan had been approved by J. Edgar Hoover: “The Director noted ‘OK’ relative to these intentions of ours.”

The name of the “established and reliable” source—the person who would be sent to intercede at Springfield College—is redacted in every instance except one. That momentary lapse by the person with the dark black marker fills in the critical puzzle piece: “It should be made clear to Saltonstall [emphasis added] that the information is being given him in the strictest of confidence with the thought that he might desire to use it in preventing King from receiving an honorary degree from Springfield College and thus save that institution from embarrassment because of King’s connections and character.”

So who was this Leverett Saltonstall? He was 71 at the time, a World War I veteran in the midst of his fourth and final term as a Republican senator from Massachusetts. He was Boston Brahmin to the core: he had Mayflower ancestry, and was the 10th generation of his family to attend Harvard, where he rowed crew and played hockey.

On April 10, 1944, when Saltonstall was a third-term governor of Massachusetts, he had been featured on the cover of Time. That article had described him in memorable fashion:

As a corporator for Springfield College—an elected but largely ceremonial role once played by John F. Kennedy (the 1956 commencement speaker)—Saltonstall was seldom consulted on college business. But in this instance, he was brought deeply into the drama, as detailed by a second FBI memo—a fascinating one penned the evening of Wednesday, April 8, by Cartha “Deke” DeLoach, one of Hoover’s top associates.

DeLoach wrote that he had met with Saltonstall on April 7, and that the senator’s response to the wiretap details on King had been stark. He “was shocked to receive this information. He stated it was hardly believable. He said if it were not for the integrity of the FBI, he would disbelieve such facts.”

DeLoach reported that the senator felt “duty bound” to share the information with Glenn Olds, whom he “described … as a very outstanding individual who could be trusted implicitly.” (Olds’ name is redacted throughout, but obvious through context.)

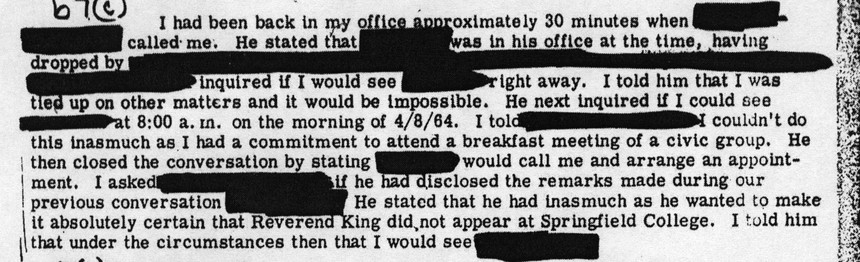

Saltonstall did indeed meet with Olds later that day, and he spread the FBI’s dirt on King—but apparently had some misgivings about doing so. He called the Bureau right back and asked if DeLoach would be willing to meet directly with Olds. DeLoach agreed to meet with the Springfield president at the FBI office on April 8 at 4 p.m.

According to DeLoach’s memo, Olds “opened the conversation by stating that he fully recognized the necessity to keep the information concerning King in strict confidence.” Olds was “very shocked” by the information provided by Saltonstall, who “had insisted that Reverend King be prevented from making the commencement address at Springfield College.”

Despite this insistence, Olds “stated that due to the fact that he will keep this information confidential, it would be impossible … to ‘uninvite’ King to make the appearance at Springfield College.”

Though he didn’t deliver the goods, Olds did leave the door ajar. A few sentences later, DeLoach reported that Olds “said he wanted to think about the possibility of preventing King from making the address but at this step of the game he did not see how it could be done.”

Before leaving, Olds “expressed a desire to shake hands with the Director some day” and indicated that Springfield College had extended to Hoover “two invitations in the recent past to receive an honorary degree and make the commencement address.”

When I spoke to him 40 years later, in 2004, Olds—then a man of 83 with some health issues—claimed that he had received a follow-up call in which DeLoach played some of the wiretapped material: “Hoover’s deputy called me to dissuade me from giving him a degree. He started to play a tape, ostensibly of King. It was filled with vulgarity. I said, ‘Are you willing to go public with this? If you go public with this, I’m happy to hear it. Otherwise I don’t want to hear any more of it.’ He said, ‘God, we can’t go public.’ So I hung up on him.”

Whether or not it went down exactly that way is hard to know, but there is at least one piece of evidence to suggest that Olds struggled under the pressure. A typed April 15 memo on onion-skin paper from Springfield College’s Director of Public Information George D. Wood Jr., addressed to Olds and cc’d to four other administrators, stated:

Olds was certainly not the first leader to ever waver on a challenging issue of principle. He thought it through again and again, trying his best to tap into his old dissertation about “The Nature of Moral Insight.” It’s impossible to know how much sleep he lost, how many soul-searching questions he posed.

But a couple of days later, on April 17, his decision had been made. The front-page headline of the Springfield student newspaper proclaimed: “World Famous Civil Rights Leader to Speak at June Commencement.” Martin Luther King was signed, sealed, and all but delivered to present the commencement address on June 14, 1964.

Until he was arrested in St. Augustine, Florida, on June 11.

King had arrived in St. Augustine in May as the filibuster for the Civil Rights Act dragged on and on. He needed a cause that would dramatize injustice and the perils of segregation, and he got more than his money’s worth in St. Augustine. The small seaside tourist attraction was brimming with symbolism. It was the nation’s oldest city, continually occupied since the Spanish arrived in 1565. Much of the black population lived in a section known as Lincolnville. And the center of the historic district was La Plaza de la Constitucion, where an open-air pavilion dating back to the early 19th century is known to this day as the slave market.

The Ku Klux Klan presence was intense in St. Augustine. King learned about the racial strife from Robert Hayling, a dentist and youth leader of the local NAACP, who had been captured, beaten, and almost burned alive at a Klan rally the previous September. Hayling had appealed to King and his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to come to St. Augustine for a campaign of direct action.

The level of violence was startling. Nighttime marches from Lincolnville to the slave market were intercepted by white supremacists, who had gathered to hear from a fiery trio. Traveling Klan “minister” Connie Lynch proclaimed, “Hitler was a great man” and described the outside agitator of choice as “Martin Lucifer Coon.” J.B. Stoner, a future lawyer for James Earl Ray, thundered, “We won’t be put in chains by no civil rights bill!” And local leader Hoss Manucy, head of the Klan-affiliated Ancient City Hunting Club, told Harpers magazine, “My boys are here to fight niggers!”

The Klansmen greeted the protesters with blackjacks, bricks, and bicycle chains. One night, Andrew Young was knocked to the ground and savagely kicked in the back and the groin. Young told me this year at a civil rights conference in Austin that St. Augustine was unique in the movement in one respect: “It was the only place where our hospital bills were greater than our bond bills.”

When King came down to St. Augustine, he was moved from place to place for his own protection. On May 28, the address of a cottage that had been rented for him was printed in the local paper; that night someone blasted it with gunfire, though King was not there. (A photo of him pointing to a bullet hole in a sliding glass door has become the St. Augustine movement’s most enduring image.)

Years later, the reporter Marshall Frady drew a memorable portrait of King during this period. Escaping from one evening’s mayhem, Frady wrote, “I happened to glimpse, in the shadows of a front porch, all by himself and apparently unnoticed by anyone else, King standing in his shirtsleeves, his hands on his hips, absolutely motionless as he watched the marchers straggling past him in the dark, bleeding, clothes torn, sobs and wails now welling up everywhere around him—and on his face a look of stricken astonishment.” He describes the man he observed in St. Augustine as “extraordinarily harrowed.”

King no doubt felt that the viability of his treasured nonviolence was in jeopardy as never before. Just one breach down in St. Augustine—no matter how understandable amid the provocation—could, in the gathering age of television, torpedo the Civil Rights Act. At a press conference on June 5, King said, “We have worked in some difficult communities, but we have never worked in one as lawless as this.” He also wired President Johnson to request federal protection, saying, “All semblance of law and order has broken down in St. Augustine.”

On June 11, the day after the filibuster was finally broken, King kept the media’s attention on the still-pending Civil Rights Act when he attempted to order food at the whites-only Monson Motor Lodge. It was the hottest day of the year, according to records from nearby Jacksonville: The sunshine blazed, the humidity was thick, the air difficult to breathe. King was arrested, along with 16 others, and under the watchful eye of segregationist sheriff L.O. Davis, he spent the night in the sweltering confines of St. John’s County Jail.

The next day, June 12, King was indicted on charges that included violating Florida’s “unwanted guest law.” He spent a few hours testifying to a grand jury about the racial climate in St. Augustine. Then he was whisked away in the back of a highway patrol car, sitting next to a German shepherd—transferred to the Duval County Jail 40 miles north in Jacksonville, apparently for his own safety.

King was still behind bars on Saturday, June 13. The commencement at Springfield College, more than 1,000 miles north, was scheduled for the next day.

Glenn Olds was stewing. As he followed the news of King’s incarceration through newspaper accounts, he worried that he was going to have to find another commencement speaker in a hurry. In our 2004 interview, he told me he had contacted St. Augustine Mayor Joseph Shelley and pleaded with him for King’s release.

“This is a very big thing for us at Springfield,” Olds remembered telling the mayor. When Shelley balked, Olds snapped that he would send college trustee Julian Sprague down to Florida in a private plane to have King record the graduation speech from behind bars. “We will broadcast King’s commencement address, not only to our students, but you will have a real national audience,” Olds said. “This will give you some real visibility. You’re holding King because he sat at a lunch counter … in America!”

Olds also told me that after the arrest he received a call from one of Springfield College’s largest benefactors, a local businessman poised to make a $1 million donation to the school. He insisted that Olds come down to his house. “His jowls, I can still see them,” Olds recalled. “He was shaking with such rage: ‘I’ve just been told you’re giving that goddamned black man an honorary degree.’” The donor allegedly opened a desk drawer, yanked out a check, and tore it up in front of Olds’ face.

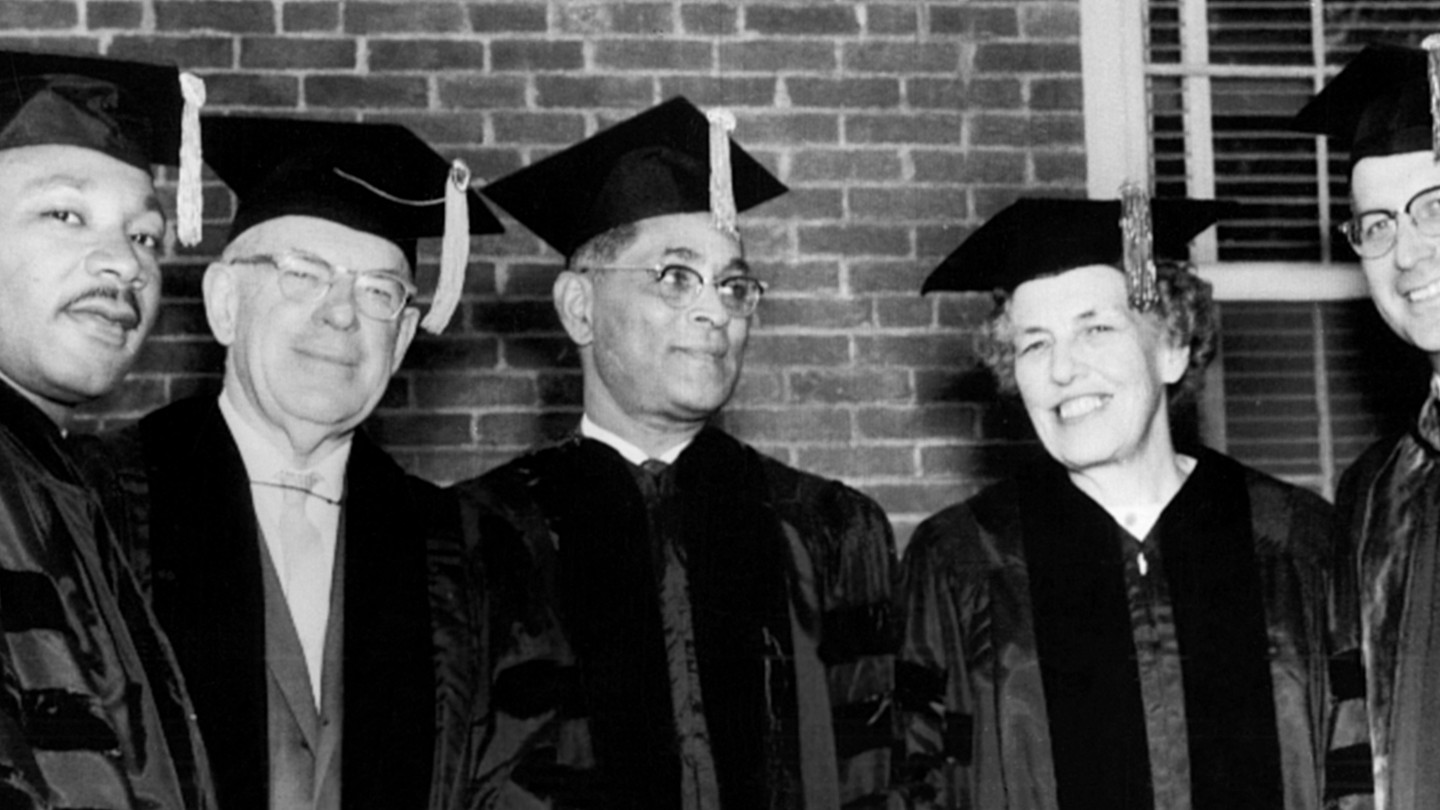

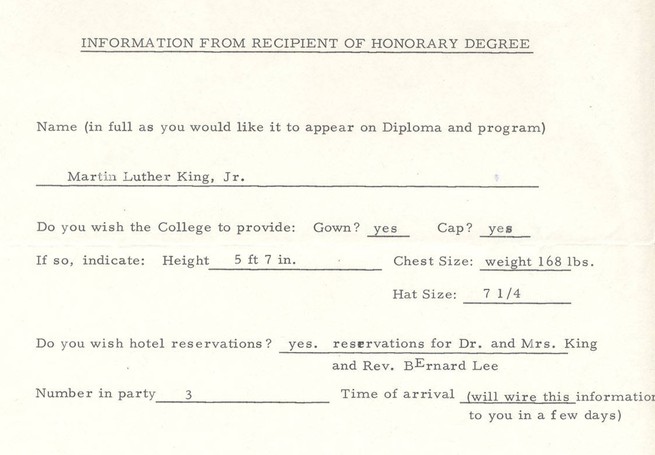

These are colorful stories, if hard to verify. This much is indisputable, though: Martin Luther King was released from jail on $900 bond on June 13. On Sunday, he landed at Bradley Air Field, along with Coretta Scott King and SCLC aide Bernard Lee. They were greeted by education professor Robert Markarian, who drove them back to Springfield. They arrived on campus, where King donned his academic regalia (a size 7 ¼ cap, and a gown to fit his 5-7, 168-pound frame, according to archival records).

The Springfield-Union reported that the college had received “scores of telephone threats” and that police had led bomb-sniffing dogs around campus in the morning. The paper also claimed that members of a Black Muslim group had distributed papers outside the Alumni Field House warning, “The next chapter may not be nonviolent.”

Inside the jam-packed building, King was introduced by Glenn Olds and then spoke for half an hour. He thanked Olds, complimented the college, and briefly referenced his time in jail in Florida (“I need not pause to say how very delighted I am to be here this afternoon. I must confess that I felt about this time yesterday afternoon that I wouldn’t be here”). He spoke about segregation (“the Negro’s burden and America’s shame”), about pacifism (“it is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence; it is either nonviolence or non-existence”), and about the importance of leading a moral life (“the time is always right to do right”). He referenced Jesus and Gandhi. He encouraged students to cultivate a “world perspective.” He implored them to consider “standing up with determination” when they encountered injustice, and “resisting it with all of one’s might.”

Many of the members of the Class of 1964 remember the speech as riveting and influential. “Anybody who was at that commencement and heard King, even if they harbored negative feelings about people of color, had to come away thinking, ‘My gosh, what a dignified, intelligent, inspirational man,’” recalled class president Kevin Gottlieb. “We didn’t know who the hell he was. He had to prove himself to all of us. And he just wiped me out. I just thought it was incredible.”

King went on to get an honorary degree at Yale the next day, then returned later in the month to Florida. On June 29, Malcolm X—recently back from his pilgrimage to Mecca—sent a Western Union telegram to King in St. Augustine that read:

It’s unknown whether Malcolm ever received a response to his telegram. What is known is this: Three days later, on July 2, 1964, Martin Luther King was back in Washington, accepting a pen from President Johnson who had just signed the Civil Rights Act into law.