Every time we try to make a getaway Gordon Brown is grabbed by another Scottish elder – just a quick word, a reminisce, a photo. This is the former prime minister in his heartland – South Lanarkshire council HQ, Hamilton, just outside Glasgow, among old-time Labour loyalists. There is lots of white hair on display, a fair amount of belly, a huge amount of shared history. He bearhugs the men, self-consciously pats women on the back with both hands, slinks his hair to the side for pictures. He even smiles. He's got a lovely smile, when it catches him unawares.

Brown, 63, and still MP for Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath, is back in frontline politics – briefly. He is on the road campaigning for a No vote in the independence referendum. For Scotland to go independent would be a betrayal of so much he has fought for. We head upstairs.

"I hear you're a Manchester City fan," he says. Ah, football – his lingua franca. Brown was never good at small talk. These days it feels as if he has three subjects – social justice, football and social justice. "It's interesting, one of my sons has become a Manchester City fan. He wants an Agüero shirt. He loves the way they play."

In a country where football is everything, it also serves as a political metaphor for Brown's vision of Scotland's role in the UK and the world at large. His son might consider himself Scottish first and foremost – as indeed does Brown – but his football team is English. But in the 21st century, we think globally as well – so the boys also support Real Madrid and Barcelona.

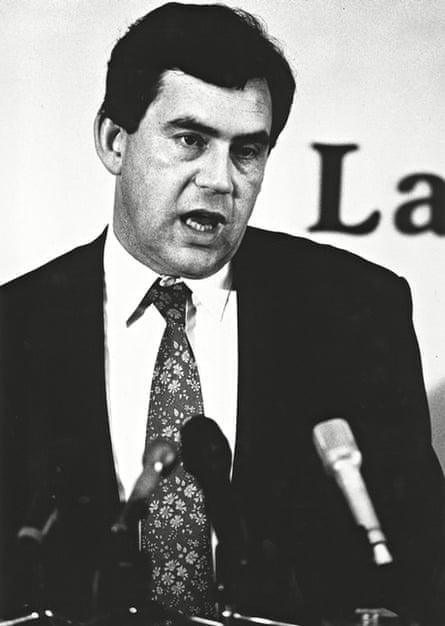

We retire to a conference room that could not be more Brown-like – austere, impersonal, a framed photograph of IT-training classes on the wall. There has always been a heaviness to his gait, but now it is more pronounced than ever. It's four years since he was voted out of office. After serving 10 years as chancellor, a decade patiently and impatiently waiting to displace Blair, he lasted three years and never won an election. Perhaps it was inevitable – who would have stood a chance after three Labour terms? Perhaps he was unlucky – who could have survived the global economic collapse? And perhaps, in the end, he was simply flawed – by paralysing indecision (not least over an early election), bitterness and what Blair cruelly called "zero emotional intelligence". Just about everybody turned on him – chancellor Alistair Darling described his behaviour in office as "appalling" and said there was a "permanent air of crisis and chaos". Harriet Harman suggested he was sexist. Cabinet secretary Gus O'Donnell warned him to "curb" his "volcanic temper". Even his friend Ed Balls said Brown found "difficulties in every situation rather than opportunities".

And yet there was something noble about Brown. For all that Blair was slick, actorly and the consummate politician, Brown was morose, cack-handed and sincere. While Blair was the grinning would-be rock star, Brown was always the son of the Presbyterian preacher man. Blair would obfuscate while appearing transparent, Brown would bare his stripped soul while insisting on privacy. If Blair was Teflon man, Brown was Bostik man.

According to friends, he gets up at 5am and works and works and works – on the referendum, in his constituency, in his role as UN special envoy for global education, on his favoured charities. He is the only former PM not to have claimed the prime minister's pension. He doesn't do much by way of relaxation beyond spending time with his wife Sarah and boys John and Fraser and watching Raith Rovers.

Before our meeting, Brown's press man asks briefly what I want to talk to him about. Mainly Scotland, I say, but I'm sure we'll touch on other stuff. He seems relaxed about this, and leaves us alone in the conference room – no spinners, no spads, no security. Highly unusual for a senior politician, let alone a former prime minister.

Brown still wants to talk football. The previous night Manchester United were beaten 4-0 by MK Dons. "You probably know I knew Alex Ferguson quite well. He's a big Labour supporter, comes from quite near where I come from and it's amazing since he left. It's the same players." There's something sad about the way Brown says "knew" in the past tense. People say that, since losing the election, he has become more socially withdrawn. I tell him I once spent three days on the road with Fergie. "Ah," he says, "what did you identify as the difference he made?" It's a classic Brown question – not what did you think of him, but how did he do it?

Brown has written a highly readable book, My Scotland, Our Britain – a series of essays about why he believes in a united Britain. It asks the same question – what difference does a United Kingdom make, and how was it achieved? It is nearly all politics, but it does touch on three generations of Brown – his father, himself and his sons. Brown is caught in the middle – his father could not have countenanced independence, I imagine his sons might well not understand what the big deal about Britain ever was, while Brown can see both sides, though firmly backs union.

Why is it so important for him to campaign for the No vote? He takes one of my Sports Mixtures and chews. "I wouldn't come back to making speeches or doing these events were it not for my children. This is a vote where you have to take into account what's going to happen 50 and 100 years down the line. You can't just vote for yourself. All the time, you're thinking what sort of country, what world, what future?"

So how does he make the case for Britain to boys who think of themselves ostensibly as Scottish? He is sitting with his blind left eye shut (an injury he got as a teenager in a rugby match) and slowly it opens. Slightly suspiciously. "No, they're eight and 10. They're interested in football, in computers. If you don't mind, I don't want to draw them into this. It's not fair. They're not wanting to express their opinion on it."

What I mean is how would he make the case to youngsters who regard their address simply as Scotland, World? Ah, he says. And he's off. "Yes, people feel more Scottish than British, there is no doubt about that. It's not surprising. But if you say you're more Scottish than British it doesn't mean you're anti-British and it doesn't mean you don't feel there is a part of you that recognises the British identity is important as well." Again, he refers to his City-supporting son. But more importantly, he says, there is all that that Britain has achieved as a united front – pensions, the welfare state, the health service, education, progressive taxation, a minimum wage. In short, a common set of values and rights. He is brilliant on the economics of the argument. A thriving jobs market for independent Scotland? Fine, he says, but 70% of the country's trade is with England. Living off oil revenues? Ridiculous, he says, Scotland would receive an estimated £2.9bn in oil revenues in 2016/17 and the pension bill alone is now £9bn. Going it alone, while still using the pound? "Instead of creating the levers of power for an independent Scotland, the SNP is suggesting a voluntary neo-colonial relationship with the rest of Britain. Scotland wouldn't have any control of the pound." Redistributive tax? "Labour proposes a top rate of tax for those earning more than £150,000, the SNP opposes it. Ed Balls proposed a bankers' bonus tax. The SNP says no. They want to cut corporation tax by 3p in the pound. That's less for health and pensions, not more."

He is never more convincing than when addressing the rally later in the evening. He struts the stage with utter self-belief – an intellectual giant who can also do a decent turn at standup. He illustrates how he is more Scottish than British, with reference to living under the national humiliation of Scotland's 9-3 defeat to England in 1962 ("One player Frank Haffey actually emigrated to Australia. Years later Denis Law went out to see him. 'Is it safe to come back?' asked Frank. And Denis's answer? 'No.'"). The audience laps it up. This is a Brown who was so rarely seen; the prime minister we could have had. He speaks fluently without notes for 40 minutes, holding out his hands as if grasping an invisible rugby ball to make his point. He jeers at the vanity of Alex Salmond when asked how the No vote can cope with his charisma ("Oh yes he's charismatic all right, aye, very humble, that Alex Salmond. Asked who were the three greatest Scotsman in history, he said the other two are Robert the Bruce and William Wallace."), is self-deprecating about his record as a leader ("A woman said to me you're better than your successor. She then said she's lived under 10 prime ministers and each was worse than the last. That put me in my place"), tells stories about presiding over Nelson Mandela's 90th birthday ("The person he most liked was Amy Winehouse. She said to him: 'You and my husband have a lot in common.' He said: 'Oh, what is that?' She said: 'You've both spent a long time in prison.'")

His analysis of why Britain has become less relevant to Scotland is equally acute – loss of empire, dilution of church power, collapse of heavy industry, denationalisation. He gets a standing ovation, and the audience is left to wonder what might have been if Brown had preceded Blair.

But upstairs, an hour earlier, it is a different story. The great communicator becomes more introverted and taciturn by the minute. We are getting on just dandy, while he delivers his thesis about Scotland. He chews sweets, extemporises, analyses along his own tramlines. Half an hour quickly passes, and I realise I've barely asked a question. Brown is not easy to interrupt in full flow, such as when he's telling me that Scotland has become estranged from Britain because of globalisation.

"But isn't it also a backlash against an England ... ?" I don't have time to complete my sentence.

"You see your thesis, if I may say so, I disagree with. Because your starting point is Scots are wanting change because England is the problem and I'm telling you the starting point is quite different. The starting point is what is happening to the global economy."

And this is where Brown becomes an intellectual bully. I begin to understand how Mrs Duffy in Rochdale – who he described as that "bigoted woman" when she dared to disagree with him –must have felt. Brown lectures me on globalisation, and still I can't get a word in.

"Every country is going to have to face up to globalisation, but Scotland has got a unique capacity because of its history as part of a multinational state to help us deal with that problem. It will require Britain to change, but it will also require it to think of what is the best relationship between Scotland, Britain and the rest of the world. And you see, you want to assume, if I may be so bold ..."

No, you can't be so bold, I say, because you've not even let me begin to make my point. It's all very well going on about globalisation, but ask Scottish people why they feel alienated from Britain, and many will mention Westminster, bankers' bonuses and the war in Iraq; they will say they don't feel politics serves their interests. "I think you're being unfair to many, many millions of decent-minded people in England, who actually feel that things have got to be fairer. What happened to the banks was a feature of what was happening in the global economy and has to be dealt with by looking at what changes you need to make in the global economy."

Did Iraq alienate people in Scotland? "You're moving on to a completely different issue. I think the problem in Iraq has been the failure to find a just peace." It's sad to hear Brown so defensive. I haven't got a clue what he means by a just peace. If he could have his time again, would he still vote for war in Iraq? "I'm not going to get into that because I don't think it's very profitable for people to look back on every decision they've made."

I ask what he thinks is his greatest political success. "People forget that between 1997 and 2010 we reduced poverty among pensioners by two-thirds. And we took two million people out of poverty. I saw my role at the treasury as using the levers of economic power to get children out of poverty and to give families better chances and to help people get employment opportunities and to deliver people from poverty in old age because it is an outrage if people have been part of the community and served it all their lives end up in poverty in retirement. So, to me, these were what we set out to do."

It's true you did much for poverty, I say, so doesn't it upset you that Labour's legacy appears to be war and the economy imploding. "I think it's the other way round; they should look at the global economy when it imploded and how we managed to get it back to growth very quickly and deal with the fundamental problem that caused the economic crisis and use international action to get us out of the crisis." In 2008, Brown was briefly feted as the world's saviour for his role in recapitalising the western banking system. Does he think history will look back on him more kindly?

But Brown is spluttering with exasperation. "I'm here to talk about the book. I want to talk about the referendum. I'm not going to talk about what has happened since 2010 or what happened in 2010, it's not what I want to talk about."

So we return to Scotland. How important is it for Labour that there is a No vote in terms of gaining an overall majority in future? "The No vote is important for the future of Scotland. You've got to put party political considerations in that respect behind you. It would be cynical of me to simply want to argue the case because a particular result would be better for Labour's chances of this or that." But it would also be human, after all you're a Labour man? "Yes, but I'm arguing the case because I don't think it's in Scotland's interests to break with a system that is basically progressive in that you pool and share resources across the UK."

I look at him in his modest blue suit, the scuffed shoes, hair sinking into the back of that bull-neck. This great growling bear of a man doesn't so much resemble a 20th-century politician as a 19th-century one. He is rigid and brusque, and yet there is so much that is admirable, heroic even, about him. You hate giving interviews, don't you, I say. "No, I don't actually. I didn't want to give interviews about ..." And now it's my time to cut him off.

Are you happier being back in Scotland? He bangs the table with his glass of water. "Look," he explodes, "I stood at the last election to stay in government, and I cannot be happy that we're out of government can I?" He is tortured by his election failure. "So I would prefer that we were still trying to take people out of poverty, or get people into jobs, or trying to build a stronger economy." You wish you were still prime minister then? "Look, I'm here to talk about the referendum. I'm sorry if you misunderstood the purpose of the interview."

I tell him I'm disappointed in him. He asks why. Because he is so unwilling to examine his legacy honestly, I say. We're both a bit emotional. He tells me to turn off the tape recorder, and says he's happy to talk to me off the record. Best stick with the record, I say.

He talks about how difficult it has been for Labour to share a platform with the Conservatives under the Better Together slogan. "I dislike intensely everything the Tories have done. I hate the bedroom tax. I feel the cuts in social security benefits are heinous at a time when they are cutting tax for the very rich. I feel very angry that poverty is rising in this country. But you've got to look at what the SNP is proposing. They're dining out on Scottish traditions of equality to suggest that Scotland will always be more just in the policies we implement, but their only tax proposal is to cut corporation tax for the richest companies in the country."

Does he feel he has suffered in politics for his Scottishness? He smiles. A genuine smile. "Well the Sun put out a particularly vicious campaign to try to suggest I was a Scottish squatter in No 10, we had Kelvin MacKenzie and Jeremy Clarkson attacking me for being Scottish. But I'm proud of being Scottish. My home has always been in Scotland even though I've been working in London for 30 years; my children have been brought up in Scotland, I feel very attached to the country."

Brown is still brooding at how the interview has gone. I'm frustrated. The strange thing is I think we like each other. I offer him a sweet. He takes it. I don't suppose you'll want me to ghost-write your autobiography, I say, as a joke.

He laughs. "I think this conversation suggests you don't want to."

"You couldn't be more wrong," I say. "You might be grumpy and unreasonable, but for me you were the moral man in politics."

"Well, I have tried all my political life to do things ... not to moralise by the way, I don't feel our job is to be alternative vicars ..." And for once he can't complete his sentence.

"You would not believe how much hope I invested in you," I say. And he looks at me, almost in pain. "Don't say it in the past tense," he pleads.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion