“Unit of three frogs at the southwest corner,” Mel barks into her phone as we approach. Usually I’d be happy to indulge in this sort of slick military patter, but since we’re currently loitering suspiciously outside the US Embassy I’d rather we kept the spy talk to a minimum. The guards are eyeing us suspiciously.

Please officer, let me explain.

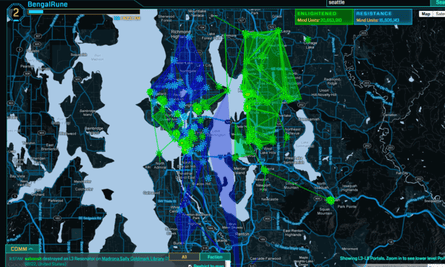

We’re playing Ingress, a massively multiplayer augmented-reality game created by Google and Niantic labs and launched last December. Participants download the dedicated app, then use their phones to log into a Google Maps-based interface; this highlights "portals" around the world – almost always well-known landmarks – that the game's two factions must fight to control. When a player is near a portal, they can take it over, set up defences and then link it together with the rest of their side's territory. Over the past six months, players have managed to create huge fields of linked portals that span several countries.

This is all happening all the time, everywhere. It’s happening right now where you live. Your city centre is probably a vital battleground between the game's two factions: the Enlightened (who believe aliens are using the portals to transcend humanity to a higher state) and the Resistance (who would rather they asked permission first). Your local town hall has probably changed hands three times today.

What I’m doing is a little more unusual, even for groups of roving transhumanist portal hackers. I’m here for an "Anomaly": a timed event organised by the developers where the two factions try and control as many portals as possible in specific areas at specific times. Anomalies don’t happen very often, but when they do they bring Ingress’ impressive player organisation to the fore.

I’m following Mel, one of the leaders of the Resistance faction for the day. Mel used to be a project manager, which is why she’s so adept at managing and coaching her troops. Now she runs a cafe in Brick Lane which serves as a hub for local Resistance agents. Today she’s leading one of the pedestrian teams (there is, I’m told, a cycle team and a motorcycle team, but I don’t see much of them as they roar off instantly, ready to tag portals beyond our reach). She’s in constant contact with the other team leaders via a chat app called Zello, hence the military lingo.

Also on the line is our dispatcher, who’s staying home for the event and co-ordinating teams throughout the city. I would love to have met her, but she’s actually in Denver, Colorado, co-ordinating teams of players half way round the world in the middle of the night. There’s also a team here from Belgium, and at least one person from South Africa. There are simultaneous events going on all over the world but London, it seems, is the place to be.

City of portals

London is Ingress central, all densely packed portals and constant threats. In more rural areas, as one player explains, the portals are further apart, and it becomes more like a hiking trip with an app involved. He tells me about how he captured a remote portal in a section of the English countryside that is inaccessible for most of the year. With no phone or wi-fi signal nearby, he had to construct a booster to throw the signal out there, connect his phone and claim it for The Resistance. He’d rather I not print where it is or how he did it. He doesn’t want the Enlightened to find it.

John Hanke is the Vice President of Niantic labs and he has even better anecdotes. He tells me about a player in Alaska who flew a bush plane to a remote airstrip to capture a key portal.

“The plane was chartered through a crowdsourced campaign by her Faction," explains Hanke. “She flew in with a blizzard coming, captured the portal just as the weather was turning and got out with the tiny plane icing up on the way out". Believe it or not, this isn't the first Ingress story I’ve heard that involves crowd-funded air travel – the other involves a sea-plane, a remote Scandinavian island and spontaneous act of sabotage.

It helps that the portals are located on local landmarks, anything from a small village train station to the Pyramid of Giza. It gives people a sense of place, of possession. That’s why I’m outside the American Embassy, drawing suspicious glances and frantically trying to shield our portals from enemy attacks. Anyone can submit a portal, you just take a picture of the location, type out a brief description and send it away for approval.

The result is that any portal-claiming expedition doubles as a walking tour of your local area, with interesting buildings and monuments highlighted and explained for you. As Hanke explains, “Wanted people to look around with fresh perspective on the places they passed by every day, looking for the unusual, the little hidden flourish or nugget of history.” I can’t help but notice it could also be a useful way to populate Google Maps, a project that Hanke was involved in before starting Niantic.

In fact Ingress serves as a sort of gigantic promotion for Google products. It’s on Android phones (although an iPhone version is coming), uses Google Maps and Streetview, has a video series on Youtube, emails your Gmail account with updates and is largely organised on Google Hangouts and G+. Hanke considers Google itself Ingress’ gaming platform, not just Android. When you’re playing Ingress you’re playing Google, and you’re paying for it by using Google. Welcome to videogames, Silicon Valley style.

Before the Anomaly, I’d played Ingress largely by myself, wandering around and taking whatever portals I could find, but the people I met in London are playing the game on another level entirely. The closest comparison I can come up with is the epic massively mutliplayer space battle game, Eve Online. Past a certain level of engagement, the organisational metagame takes over and becomes the entire point of playing. The difference is that Eve players are fighting over imaginary virtual planets, rather than Nelson’s Column.

Hanke is fairly open about the game's reliance on user-generated narratives. He calls Ingress an “entertainment enabler”. “The game itself is the motivation," he says. "But it’s the social interaction and exploration that the game encourages that are the real payoffs. People who meet up with other players and go on adventures together have the most fun and therefore tend to be some of the most dedicated and enthusiastic participants.”

This kind of co-operation is part accident, part design. “We planned some things” says Hanke “Like game rules that require eight players to work together to build the highest level Portals.” But other times, they “got lucky”. He explains an event Niantic created called the "Shard Game" where factions had to move shards from portal to portal across the globe. Niantic's team knew this would force agents in different countries to co-operate, what they didn’t know is that those links would last. Now those organisations are used to plan global strategies for each faction, and sometimes they surprise everyone, like the time agents in Israel and Syria co-operated to create a giant control field encompassing most of the Middle East.

The secret master plan

Just as we’re leaving the embassy, much to the relief of the guards, there’s a change on my map. The screen takes on a fuzzy blue sheen. A field! Someone has connected three portals together, creating a huge triangle covering the playing area. I zoom out to get a better look. And out. And out. Then someone shows me a map, it covers the entire south east of England.

My companions have been holding out on me, they had a secret master plan all along. Last night, various Resistance agents journeyed around the south of England in order to create a monster field encompassing the entirety of today’s playing area. It’s hard to explain just how much of an achievement this is: links can’t pass through other links, so agents had to walk the entire breadth of the line, carefully removing anything standing in their way. Then they had to manually ferry portal keys back and forth between the three points so each one could connect to the other.

I’m not entirely clear what affect this has on the scoring system, but since we were already doing well, it puts us way over the top.

By the time the day is done, I have sore feet, a dead phone battery, some great stories and a standing invitation to join my local Resistance cell. I’m not entirely sure if I will, as much as I enjoyed the day. I’m not entirely sure I have room in my life for a hobby as big as this one, but I’m still glad Ingress exists. To revisit the Eve Online comparison, it’s a game I like to hear about even if I’m not playing it. The stories of players sailing out to remote islands, scaling mountains and co-ordinating across countries never quite get old.

Hanke told me their key phrase for Ingress was “see with new eyes”. He was talking about landmarks and portals, but to me it means the players. Teams of agents are fighting a secret war for control of my local post office. I know that now and I can’t unknow it. The world is just a little bit more interesting as a result.

Tell me a story: augmented reality technology in museums

How augmented reality builds bridge between games and children's books

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion