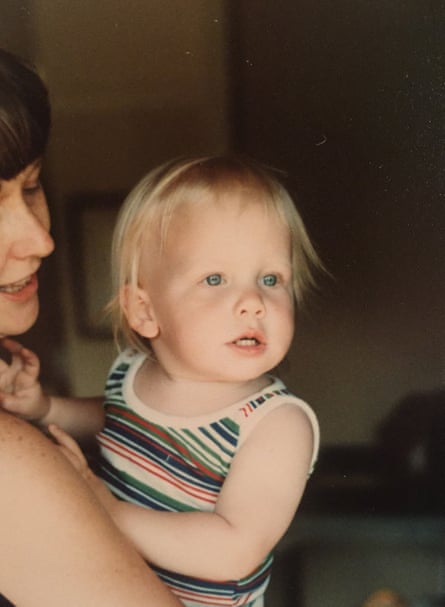

I’ve always been a great big person. In the months after I was born, the doctor was so alarmed by the circumference of my head that she insisted my parents bring me back, over and over, to be weighed and measured and held up for scrutiny next to the “normal” babies. My head was “off the charts”, she said. Science literally had not produced a chart expansive enough to account for my monster dome. “Off the charts” became a West family joke over the years – I always deflected it, saying it was because of my giant brain – but I absorbed the message nonetheless. I was too big, from birth. Abnormally big. Medical-anomaly big. Unchartably big.

There were people-sized people, and then there was me. So, what do you do when you’re too big, in a world where bigness is cast not only as aesthetically objectionable, but also as a moral failing? You fold yourself up like origami, you make yourself smaller in other ways, you take up less space with your personality, since you can’t with your body. You diet. You starve, you run until you taste blood in your throat, you count out your almonds, you try to buy back your humanity with pounds of flesh.

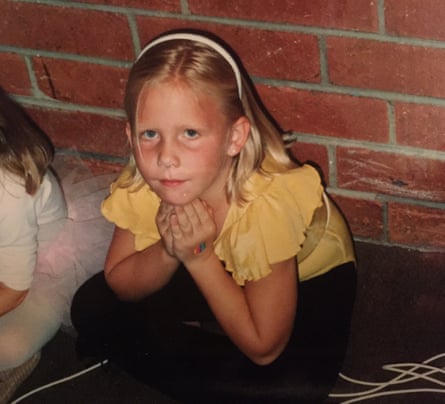

I got good at being small early on – socially, if not physically. In public, until I was eight, I would speak only to my mother, and even then only in whispers, pressing my face into her leg. I retreated into fantasy novels, movies, computer games and, eventually, comedy – places where I could feel safe, assume any personality, fit into any space. I preferred tracing to drawing. Drawing was too bold an act of creation, too presumptuous.

My dad was friends with Bob Dorough, an old jazz guy who wrote all the songs for Multiplication Rock, an educational kids’ show and Schoolhouse Rock’s maths-themed sibling. He’s that breezy, froggy voice on Three Is a Magic Number – if you grew up in the US, you’d recognise it. “A man and a woman had a little baby, yes, they did. They had three-ee-ee in the family ...” Bob signed a vinyl copy of Multiplication Rock for me when I was two or three years old. “Dear Lindy,” it said, “get big!” I hid that record as a teenager, afraid that people would see the inscription and think: “She took that a little too seriously.”

I dislike “big” as a euphemism, maybe because it’s the one chosen most often by people who mean well, who love me and are trying to be gentle with my feelings. I don’t want the people who love me to avoid the reality of my body. I don’t want them to feel uncomfortable with its size and shape, to tacitly endorse the idea that fat is shameful, to pretend I’m something I’m not out of deference to a system that hates me. I don’t want to be gentled, like I’m something wild and alarming. (If I’m going to be wild and alarming, I’ll do it on my terms.) I don’t want them to think I need a euphemism at all.

“Big” is a word we use to cajole a child: “Be a big girl!” “Act like the big kids!” Having it applied to you as an adult is a cloaked reminder of what people really think, of the way we infantilise and desexualise fat people. Fat people are helpless babies enslaved by their most capricious cravings. Fat people don’t know what’s best for them. Fat people need to be guided and scolded like children. Having that awkward, babyish word dragging on you every day of your life, from childhood into maturity, well, maybe it’s no wonder I prefer hot chocolate to whisky and substitute Harry Potter audiobooks for therapy.

Every cell in my body would rather be “fat” than “big”. Grownups speak the truth.

Over time, the knowledge that I was too big made my life smaller and smaller. I insisted that shoes and accessories were just “my thing”, because my friends didn’t realise I couldn’t shop for clothes at regular shops and I was too mortified to explain it to them. I backed out of dinner plans if I remembered the restaurant had particularly narrow aisles or rickety chairs. I ordered salad even if everyone else was having fish and chips. I pretended to hate skiing because my giant men’s ski pants made me look like a chimney and I was terrified my bulk would tip me off the chairlift. I stayed home as my friends went hiking, biking, sailing, climbing, diving, exploring – I was sure I couldn’t keep up, and what if we got into a scrape? They couldn’t boost me up a cliff or lower me down an embankment or squeeze me through a tight fissure or hoist me from the hot jaws of a bear. I never revealed a single crush, convinced that the idea of my disgusting body as a sexual being would send people – even people who loved me – into fits of projectile vomiting (or worse, pity). I didn’t go swimming for a decade.

As I imperceptibly rounded the corner into adulthood – 14, 15, 16, 17 – I watched my friends elongate and arch into these effortless, exquisite things. I waited. I remained a stump. I wasn’t jealous, exactly; I loved them, but I felt cheated.

We each get just a few years to be perfect. To be young and smooth and decorative and collectible. That’s what I’d been sold. I was missing my window, I could feel it pulling at my navel (my obsessively hidden, hated navel), and I scrabbled, desperate and frantic. Deep down, in my honest places, I knew it was already gone – I had stretch marks and cellulite long before 20 – but they tell you that, if you hate yourself hard enough, you can grab a tail feather or two of perfection. Chasing perfection was your duty and your birthright, as a woman, and I would never know what it was like – this thing, this most important thing for girls.

I missed it. I failed. I wasn’t a woman. You only get one life. I missed it.

Society’s monomaniacal fixation on female thinness isn’t a distant abstraction, something to be pulled apart by academics in women’s studies classrooms or leveraged for traffic in shallow “body-positive” listicles (“Check Out These 11 Fat Chicks Who You Somehow Still Kind of Want to Bang – No 7 Is Almost Like a Regular Woman!”). It is a constant, pervasive taint that warps every woman’s life. And, by extension, it is in the amniotic fluid of every major cultural shift.

Women matter. Women are half of us. When you raise women to believe that we are insignificant, that we are broken, that we are sick, that the only cure is starvation and restraint and smallness; when you pit women against one another, keep us shackled by shame and hunger, obsessing over our flaws, rather than our power and potential; when you leverage all of that to sap our money and our time – that moves the rudder of the world. It steers humanity toward conservatism and walls and the narrow interests of men, and it keeps us adrift in waters where women’s safety and humanity are secondary to men’s pleasure and convenience.

I watched my friends become slender and beautiful, I watched them get picked and wear J Crew and step into small boats without fear, but I also watched them starve and harm themselves, get lost and sink. They were picked by bad people, people who hurt them on purpose, eroded their confidence and kept them trapped in an endless chase. The real scam is that being bones isn’t enough, either. The game is rigged. There is no perfection.

I listened to Howard Stern every morning in college on his eponymous 90s radio show. The Howard Stern Show was magnificent entertainment. It felt like a family. Except that, for female listeners, membership in that family came at a price. Stern would do this thing (the thing, I think, that most non-listeners associate with the show) where hot chicks would turn up at the studio and he would look them over like a horse vet – running his hands over their withers and flanks, inspecting their bite and the sway of their back, honking their massive horse jugs – and tell them, in intricate detail, what was wrong with their bodies. There was literally always something. If they were eight stone, they could stand to be seven. If they were six, gross. (“Why did you do that to your body, sweetie?”) If they were a C cup, they’d be hotter as a DD. They should stop working out so much – those legs are too muscular. Their 29in waist was subpar – come back when it’s a 26.

Then there was me: 16 stone, 40in waist, no idea what bra size, because I’d never bothered to buy a nice one, because who would see it? Frumpy, miserable, cylindrical. The distance between my failure of a body and perfection stretched away beyond the horizon. According to Stern, even girls who were there weren’t there.

If you want to be a part of this community that you love, I realised – this family that keeps you sane in a shitty, boring world, this million-dollar enterprise that you fund with your consumer clout, just as much as male listeners – you have to participate, with a smile, in your own disintegration. You have to swallow, every day, that you are a secondary being whose worth is measured by an arbitrary, impossible standard administered by men.

When I was 22 and all I wanted was to blend in, that rejection was crushing and hopeless and lonely. Years later, when I was finally ready to stand out, the realisation that the mainstream didn’t want me was freeing and galvanising. It gave me something to fight for. It taught me that women are an army.

When I look at photographs of my 22-year-old self, so convinced of her own defectiveness, I see a perfectly normal girl and I think about aliens. If an alien – a gaseous orb or a polyamorous cat person or whatever – came to Earth, it wouldn’t even be able to tell the difference between me and Angelina Jolie, let alone rank us by hotness. It’d be like: “Uh, yeah, so those ones have the under-the-face fat sacks, and the other kind has that dangly pants nose. Fuck, these things are gross. I can’t wait to get back to the omnidirectional orgy gardens of Vlaxnoid.”

The “perfect body” is a lie. I believed in it for a long time, and I let it shape my life, and shrink it – my real life, populated by my real body. Don’t let fiction tell you what to do. In the omnidirectional orgy gardens of Vlaxnoid, no one cares about your arm flab.

Fat female role models

As a kid, I never saw anyone remotely like myself on TV. Or in the movies, or in video games, or at the children’s theatre, or in books, or anywhere at all in my field of vision. There simply were no young, funny, capable, strong, good fat girls. A fat man can be Tony Soprano, he can be Dan from Roseanne (still my No 1 celeb crush), he can be John Candy, funny without being a human sight gag. But fat women were sexless mothers, pathetic punch lines or gruesome villains. Don’t believe me? It’s cool –I wrote it down.

Here is a list of fat female role models available in my youth.

Lady Kluck was a loud, fat chicken-woman who took care of Maid Marian (and, presumably, may have wet-nursed her with chicken milk?!) in Disney’s Robin Hood.

Kluck was so fat, in fact, that she was nearly the size of an adult male bear. Being a 28-stone chicken, she wasn’t afraid to throw down in a fight with a lion and a gay snake (even though the lion was her boss! #LeanIn), and she had monstro jugs, but in a maternal, sexless way, which is a total rip-off. (It’s weird that motherhood is coded as sexless, by the way. I know most of society is clueless about the female reproductive system, but if there’s one thing most babies have in common it’s that your dad goofed in your mum.)

Baloo dressed as a sexy fortune-teller

In order to assist Robin Hood in ripping off Prince John’s bejewelled decadence caravan, Baloo (I know this bear’s name is technically Little John, but he is clearly a character played by a bear actor named Baloo who also plays himself in The Jungle Book) adorns himself with scarves and rags and golden bangles and whirls around like an impish sirocco, utterly beguiling PJ’s guard rhinos and incapacitating them with boners. Baloo dressed as a sexy fortune-teller luxuriates in every curve of his huge, sensuous bear butt; self-consciousness is not in his vocabulary. He knows he looks good. The most depressing thing I realised while making this list is that Baloo dressed as a sexy fortune-teller was the most positive role model of my youth.

I don’t even know this bitch’s deal. In Alice in Wonderland, her only personality trait is “likes the colour red”. She doesn’t seem to do any governing, aside from executing minors for losing at croquet, and she is married to a 1ft-tall baby with a moustache. She is, now that I think about it, the perfect feminazi caricature: fat, loud, irrational, violent, overbearing, constantly hitting a hedgehog with a flamingo. Oh, shit. She taught me everything I know.

I am deeply torn on Piggy. For a lot of fat women, Piggy is it. She is powerful and uncompromising, assertive in her sexuality and wholly self-possessed, with an ostentatious glamour usually denied to anyone over a size eight. Her being a pig affords fat fans the opportunity to reclaim that barb with defiant irony – she invented glorifying obesity.

But also, you guys, Miss Piggy is kind of a rapist. Maybe if you love Kermie so much you should respect his bodily autonomy. The dude is physically running away from you.

A depressed turtle from The NeverEnding Story who’s so fat and dirty people literally get her confused with a mountain.

I guess it’s forgivable that one of the secondary antagonists of The Secret of NIMH is a shrieking shrew of a woman who is also a literal shrew named Auntie Shrew, because the hero of the movie is also a lady and she is strong and brave. But, like, seriously? Auntie Shrew? Thanks for giving her a pinwheel of snaggle-fangs to go with the cornucopia of misogynistic stereotypes she calls a personality.

Sure, the Trunchbull in Matilda is a bitter, intractable, sadistic she-monster who doesn’t even feel a shred of fat solidarity with Bruce Bogtrotter (seriously, Trunch?), but can you imagine being the Trunchbull? And growing up with Miss Effing Honey? The world is not kind to big, ugly women. Sometimes, bitterness is the only defence.

Question: how come, when the teapot and cup turn back into humans at the end of Beauty and the Beast, Chip is a four-year-old boy, but his mother, Mrs Potts, is like 107? Perhaps you’re thinking: “Lindy, you’re remembering it wrong. That kindly, white-haired, snowman-shaped Mrs Doubtfire situation must be Chip’s grandmother.” Not so, champ! She’s his mum. Look it up. She gave birth to him four years ago. Also, where the hell is Chip’s dad? Could you imagine being a 103-year-old single mum?

As soon as you become a mother, apparently, you are instantly interchangeable with the oldest woman in the world, and/or a pot of boiling brown water with a hat on it.

Extracted from Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman by Lindy West, published on 19 May by Quercus, £16.99. To buy a copy for £9.99, visit bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion