There are a dozen factors that make Japanese food so special – ingredient obsession, technical precision, thousands of years of meticulous refinement – but chief among them is one simple concept: specialisation. In the west, where miso-braised short ribs share menus with white truffle pizza and sea bass ceviche, restaurants cast massive nets to try to catch as many fish as possible but, in Japan, the secret to success is choosing one thing and doing it really well. Forever.

The concept of shokunin, an artisan deeply and singularly dedicated to their craft, is at the core of Japanese culture. Japan’s most famous shokunin these days is Jiro Ono, immortalised in the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, but you will encounter his level of relentless focus across the entire food industry. Behind closed doors. Down dark alleyways. Hiding in every corner of this country. The 80-year-old tempura man who has spent six decades discovering the subtle differences yielded by temperature and motion. The 12th-generation unagi sage who uses metal skewers like an acupuncturist uses needles, teasing the muscles of wild eel into new territories. The young man who has grown old at his father’s side, measuring his age in kitchen lessons. Any moment now, it will be his turn to be the master and, when he is, he’ll know exactly what to do.

Japan is the land of a million shokunin, dedicated artisans who bless this country with their quiet pursuit of perfect. Here are four I encountered during the year I spent researching my book, Rice, Noodle, Fish.

Tokyo

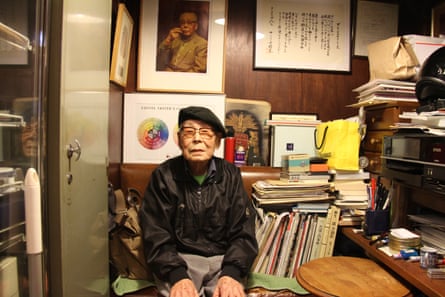

Ichiro Sekiguchi of Café de l’Ambre

This sound engineer from Tokyo was serving in the second world war when he learned that coffee beans purchased by Germans were being stored on the outskirts of the city. When the war ended, he went into the coffee business, using what he could of the beans left to languish as the Axis powers met defeat. By the time he opened Café de l’Ambre in the Ginza district in 1948, he was brewing five-year-old beans from Sumatra. What was born out of necessity turned into a groundbreaking technique. “The coffee had a rich, full taste, like good wine.”

Today, L’Ambre offers a wide selection of global vintages: ’93 Brazil, ’76 Mexico and, the oldest, a Colombian bean from 1954. At 101 years old, Ichiro still shows up to work every day to toast his ancient beans on a roaster he helped to design himself decades back. The classic kissaten (traditional Japanese coffee shop), the old beans, and the man himself stand as a stubborn rebuke to the wave of chain coffee outlets, convenience stores and vending machines that sprang up during Japan’s boom years and today make up the vast majority of the coffee market.

I settle onto a stool at the long countertop and choose a cup of Cuban coffee from 1974. A middle-aged barista in a striped turtleneck spends 10 minutes dribbling hot water in concentric circles through a vintage Japanese sock filter. The coffee is like nothing I’ve tasted before, with a round, vegetal quality and only the faintest hint of acidity.

It is not Tokyo’s finest cup of coffee. But Ichiro trades in something more than technical precision – he offers a taste of the past, a reminder there’s another way to do things.

On my way out, Ichiro is sitting in his office, hands on his knees, a picture of him as a younger man hanging on the wall over his shoulder. He looks worried. “My supplies are down,” he tells me. “I used to have five tons of coffee ageing in my storage, but now I’m down to less than a ton.” The soul of a shokunin: a 101-year-old man worried about inventory.

“What’s your secret, Ichiro-san?” I ask.

“Coffee, of course. I drink at least five cups a day.”

8-10-15 Ginza, Chuo-ku, h6.dion.ne.jp/~lambre

Kyoto

Shunichi Matsuno of Tempura Matsu

The taxi pulls up at a freestanding two-storey wooden building that looks like someone’s riverside residence. As we step inside, I realise that it’s actually a restaurant but it doesn’t look like any of the kaiseki (traditional dinner) places I’ve eaten in before: small and creaky with a handful of tables and a long counter – more an izakaya than a sanctuary for quiet reflection. I see two sets of chopsticks, two sake glasses, and two stalks of bamboo set at the bar. We take a seat and Shunichi and his son Toshio join two other cooks behind the counter. Packed inside the bamboo is a sorbet made from shiso, a herb with a flavour between mint and basil. My companion gives a nod and the procession begins.

We start with a next-generation miso soup: Kyoto’s famous sweet white miso whisked with a dashi (broth) made from lobster shells, with large chunks of tender claw meat and wilted spinach bobbing on the soup’s surface.

The son takes a cube of top-flight wagyu beef off the grill, charred on the outside, rare in the centre and swaddles it in green onions and a scoop of melted sea urchin – a surf and turf to end all others.

The father lays down a gorgeous ceramic plate with a poem painted on its surface. “From the 16th century,” he tells us, then goes about constructing the dish with his son, piece by piece. First a chunk of tilefish wrapped around a grilled matsutake mushroom stem. Then a thick triangle of grilled mushroom cap, plus another grilled stem, topped with mushroom miso. A pickled ginger shoot, a few tender soybeans, and the crowning touch, the tilefish skin, separated from its body and fried into a rippled wave of crunch.

The rice course arrives in a small bamboo steamer. The young chef works quickly. He slices curtains of tuna belly from a massive, fat-streaked block, dips it briefly in house-made soy sauce, then lays it on the rice. Over the top, he spoons a sauce of seaweed and crushed sesame seeds just as the tuna fat begins to melt into the grains below.

A round of tempura comes next: a harvest moon of creamy pumpkin, a golden nugget of blowfish capped with a translucent daikon sauce and, finally, a soft, custardy chunk of salmon liver, intensely fatty with a bitter edge, a flavour I’ve never tasted before.

The last savoury course comes in a large ice block carved into the shape of a bowl. Inside, there’s a nest of soba noodles tinted green with powdered matcha, floating in a dashi charged with citrus and topped with a false quail egg, the white fashioned from grated daikon. The chefs cheer as I lift the block to my lips.

It happens fast, 10 courses in just over an hour – so quickly there’s no time for talking or processing everything they serve us – but, by the time we emerge from the restaurant, I know I’ve just eaten one of the great meals of my life.

21-26 Umezu Onawaba-cho, Ukyo-ku, lunch £32, dinner £65

Fukuoka

Hideki Irie of Mengekijo Genei

The use of monosodium glutamate causes heated debate in the ramen community. In some kitchens, tubs of MSG sit like salt and pepper, spooned into each bowl before being passed across the counter. But many young, modern ramen chefs are on a mission to find maximum flavour without MSG.

This became Irie’s obsession. He started out by learning to brew his own soy sauce. “Almost all chefs buy soy in the store, but the product is lousy. If I developed my own soy, nobody could copy my recipe.” The resulting potion took a year to master and costs ¥22,600 (£140) a litre to make – but, Irie says, it is well worth the money.

“Joel Robuchon wanted to buy it from me, and I told him no,” he says, speaking of the Frenchman dubbed by Michelin guides “the greatest chef of the century”.

“I don’t want Robuchon copying my ramen.”

With the super soy calibrated, he set about tinkering with different combinations of umami-rich products until he found the perfect mix for his tare (dipping sauce): kelp, shitakes, bonito, oysters, sardines, mackerel, dried scallops, and dried abalone.

After listening to him talk about his top-secret tare, his homemade soy sauce, his years spent studying MSG, you get the sense that the ¥800 (£5) he charges for a bowl may represent one of the greatest bargains in the entire food world.

Irie serves me three ramens, including a bowl made with a rich dashi and head-on shrimp, and another studded with spicy ground pork and wilted spinach and lashed with chilli oil. Both are exceptionally delicious, sophisticated creations, but it’s his interpretation of tonkotsu that leaves me muttering softly to myself. The noodles are firm and chewy, the roast pork is striped with soft deposits of warm fat, and the toppings – white curls of shredded spring onion, chewy strips of bamboo, a perfect square of toasted seaweed – are skilfully applied. The combination of tare, the culmination of years of careful tinkering, and broth, made from whole pig heads and knots of ginger, defies the laws of tonkotsu: a soup with the savoury, meaty intensity of a broth made from a thousand pigs that’s light enough to leave you wanting more. And more. And more.

“I have no doubt that I make the best bowl of ramen in Japan,” Irie says. Fighting words, to be sure, but the man may have a point.

2-16-3 Yakuin, Chuo-ku

Hokkaido

Tatsuru Rai of Raku-ichi

Tatsuru Rai built Raku-ichi himself, fashioning a 12-seat bar into a quiet viewing area for the performance that unfolds in the kitchen. He makes every order of soba by hand, working in small batches so that by the time you’ve eaten, you’ll have witnessed the extraordinary transformation of grain and water into noodle. It takes him eight minutes from start to finish, a process so intimate that you blush every time he looks up from his work area.

He starts with 100% local buckwheat – a grain stubborn enough that most soba masters cut their dough with wheat flour to make it easier to work with. Once the water is added and the dough shaped into a smooth, seamless ball, he works it with a wooden dowel, using his forearms and his palms to make the mass thinner and thinner. With each pass of the dowel, he pats the dough with his right hand, a quick, seamless motion that acts as a metronome for the elaborate rolling process. The thud of the dowel, the slap of the hand, the rustle of the buckwheat against the board: it starts soft, grows louder and faster, like the building of a great jazz performance. He rolls, slaps, rotates, rolls, slaps, rotates, rolls, slaps, rotates – over and over until the crude circle is shaped into a sharp rectangle. With a 12-inch soba blade and a wooden board to guide him, he transforms the rectangle into thousands of dark brown strands. No wasted motion, no alien movements, not a scrap of dough lost to inexactitude or impatience.

Nobody talks, as if too much breath might break the magical bond of buckwheat and water.

The soba comes two ways: seiro, afloat in a dark, hot dashi spiked with slices of duck breast; or kake, cold and naked, to be dipped into a concentrated version of that same broth. Even if it’s freezing outside and you’ve lost all sensation in your toes, eat these noodles cold, so the elegant chew and earthy taste of the buckwheat is uncompromised by the heat of the dashi.

“The process is everything,” Tatsuru says, in what could be a four-word definition of Japan.

The young man next to me, a spiky-haired pop star from Sapporo, shakes his head in agreement. “Once you eat here, it’s hard to go back,” he says, in what could be a nine-word definition of Hokkaido.

This is an edited extract from Rice Noodle Fish by Matt Goulding, with a foreword by Anthony Bourdain, published on 24 March by Hardie Grant books at £16.99. To order a copy for £12.99, including UK p&p, visit bookshop.theguardian.com. Matt Goulding is co-founder of the travel blog roadsandkingdoms.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion