A Fleet of Taxis Did Not Really Save Paris From the Germans During World War I

The myth of the Battle of the Marne has persisted, but what exactly happened in the first major conflict of the war?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/75/6075cc1d-3b88-4012-aba9-25afb9b79247/paris_taxis_marne-1.jpg)

On the night of September 6, 1914, as the fate of France was hanging in the balance, a fleet of taxis drove under cover of darkness from Paris to the front lines of what would become known as the Battle of the Marne. Carrying reinforcements that turned the tide of battle against the Germans, the taxi drivers saved the city and demonstrated the sacred unity of the French people.

At least, that’s the story.

Still, as we know from our own past, heroic stories about critical historic moments such as these can have but a grain of truth and tons of staying power. Think Paul Revere, who was just one of three riders dispatched the night of April 18, 1775, who never made it all the way to Concord and who never said, “The British are coming!”

Yet, his legend endures, just as it does, a century later, with the Taxis of the Marne—which really did roll to the rescue, but weren’t remotely close to being a decisive factor in the battle. That doesn’t seem to matter in terms of their popularity, even today.

“When we welcome school children to the museum, they don’t know anything about the First World War, but they know the Taxis of the Marne,” says Stephane Jonard, a cultural interpreter at La Musee de la Grand Guerre, France’s superb World War I museum, located on the Marne battlefield, near Meaux, about 25 miles east of Paris.

One of the actual taxis is on exhibit in the Museum, and in the animated wall map that shows the movements of troops, the arrival of reinforcements from Paris is shown through the icon of a taxi.

For Americans, understanding why the taxis are still fondly remembered a century later requires a better grasp on the pace of events that roiled Europe a century ago. Consider this: the event generally considered the match that ignited the already bone-dry timber of European conflict—the assassination of Austria’s Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo—took place on June 28, 1914. A flurry of declarations of war and a dominos-like series of military mobilizations followed so quickly that less than eight weeks later, German armies were already rolling through Belgium and into France, in what the German high command hoped would be a lightning strike that would capture Paris and end the war quickly.

“The Germans gambled all on a brilliant operational concept,” wrote historian Holger H. Herwick in his 2009 book, The Marne: 1914. “It was a single roll of the dice. There was no fallback, no Plan B.”

***

This early phase of the conflict that would eventually engulf much of the world was what some historians call “The War of Movement” and it was nothing like the trench-bound stalemate that we typically envision when we think of World War I.

Yet even in these more mobile operations, losses were staggering. The clash between the world’s greatest industrial and military powers at the time was fought on the cusp of different eras. Cavalry and airplanes, sword-wielding officers and long-range artillery, fife and drums and machine guns, all mixed anachronistically in 1914. “Masses of men advanced against devastatingly powerful modern armaments in the same fashion as warriors since ancient times,” writes Max Hastings in his acclaimed 2013 book Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes To War. “The consequences were unsurprising, save to some generals.”

On August 22, 27,000 French soldiers were killed in just one day of fighting near the Belgian and French borders in what has become known as the Battle of the Frontiers. That’s more than any nation had ever lost in a single day of battle (even more infamous engagements later in World War I, such as the Battle of the Somme, never saw a one-day death tally that high.)

The Battle of the Marne took place two weeks after that at the Battle of the Frontiers and with most of the same armies involved. At that point the Germans seemed unstoppable, and Parisians were terrified over the very real prospect of a siege of the city; their fears hardly assuaged by the appearance of a German monoplane over the city on August 29 that lobbed a few bombs. The government decamped for Bordeaux and about a million refugees (including the writer Marcel Proust) followed. As Hastings relates in his book, a British diplomat, before burning his papers and exiting the city himself, fired off a dispatch warning that “the Germans seem sure to succeed in occupying Paris.”

Is it any wonder that the shocked, grieving and terrified citizens of France need an uplifting story? A morale boost?

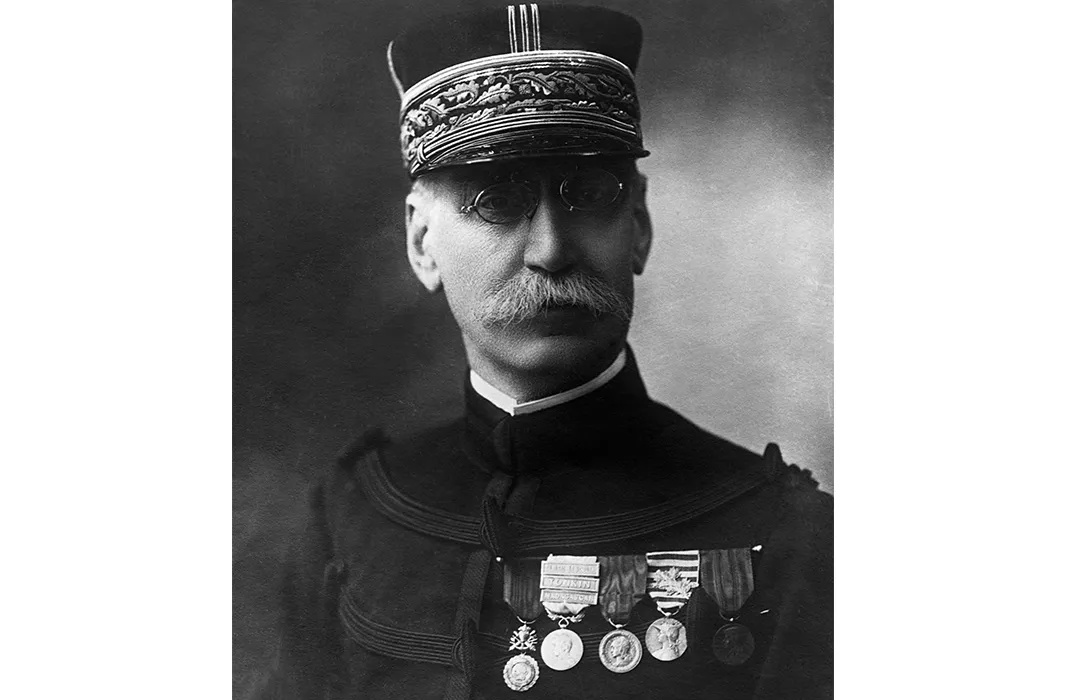

Enter Gen. Joseph Gallieni, one of France’s most distinguished military men, who had been called from retirement to oversee the defense of Paris. The 65-year-old took command with energy and enthusiasm, shoring up defenses and preparing the city for a possible siege.

“Gallieni’s physical appearance alone commanded respect,” wrote Herwig. “Straight as an arrow and always immaculate in full-dress uniform, he had a rugged, chiseled face with piercing eyes, a white droopy mustache and a pince-nez clamped on the bridge of his nose.”

An old colleague of the French commander-in-chief General Joseph Joffre, Gallieni knew what was unfolding out in the expansive farmlands around Meaux. By September 5, the German armies had reached the area, hell-bent for Paris, only 30 miles away. They were following a script developed by the German high command before the war that called for a rapid encirclement of the city and the Allied armies.

Gallieni knew that Joffre needed all the men he could get. Trains and trucks were commandeered to rush reinforcements to the front. So were taxis, which, even as early in the automobile’s history as 1914, were a ubiquitous part of Parisian life. However, of the estimated 10,000 taxis that served the city at that time, 7,000 were unavailable, in large part because most of the drivers were already in the army. Still, those that could respond, did. In some cases, whether they liked it or not: “In every street in the capital,” wrote Henri Isselin in his 1966 book The Battle of the Marne, “police had stopped taxis during working hours, turned out the passengers, and directed the vehicles towards the Military College, where they were assembled.”

While the taxis were being commandeered, an epic battle was developing east of Paris. Today, the wide open farm fields around Meaux, itself a charming Medieval city, are much the way they were in 1914. Bicyclists whizz down the roads that bisect the fields and small villages, often passing memorials, mass graves and ancient stone walls still pockmarked with bullet holes. One hundred years ago, there would have been nothing bucolic or peaceful here. What was then the largest battle in history was about to be fought on this land.

***

On the night of September 6, the first group of taxis assembled on the Place des Invalides—next to the military compound in Paris’s 7th arrondisement. Many were from the G-7 cab company, which still exists today. The taxis of 1914 were Renault AG1 Landaulets. They could seat five men per vehicle, but averaged a speed of only about 20-25 miles per hour. With orders from the French command, the first convoy of about 250 left the plaza and headed out of the city on National Road 2. Chugging along single-file, the taxi armada crept towards the fighting, their mission still secret. They were soon joined by another fleet of cabs.

“The drivers were far from happy,” wrote Isselin. “What was the point of the nocturnal sortie? What was going to happen to them?” At first, the whole exercise seemed pointless. On September 7, the officers directing the convoy couldn’t find the troops they were supposed to transport. Somewhere outside of Paris, Hastings notes, “they sat in the sun and waited hour after hour, watching cavalry and bicycle units pass en route to the front, and giving occasional encouraging cries. ‘Vive les dragons! Vive les cyclistes.”

Finally that night, with the rumble of artillery audible in the distance, they found their passengers: Three battalions of soldiers. Yet another convoy picked up two more battalions. The troops, for the most part, were delighted to find that they would be taxied to the front. “Most had never ridden in such luxury in their lives,” Hastings writes.

Although estimates vary on the final count, by the morning of September 8, the taxis had transported about 5,000 men areas near the front the front lines where troops were being assembled. But 5,000 men mattered little in a battle involving more than one million combatants. And as it turned out, most of the troops carried by taxi were held in reserve.

Meanwhile, a stunning turn of events had changed the shape of the battle.

What happened, essentially, is that one of the German generals, Alexander von Kluck, had decided to improvise from the high command’s plan. He had opted to pursue the retreating French armies, who he (and most of his fellow commanders) believed were a shattered, spent force. In doing so, he exposed his flank, while opening up a wide gap between his and the nearest German army. The white-haired, imperturbable Joffre—known to his troops as Papa—sprang into action to exploit Kluck’s move. He counterattacked, sending his troops smashing into von Kluck’s exposed flank.

Still, the battle swung back and forth, and the French commander needed help. In a famous scene often recounted in histories of the Marne, Joffre lumbered over to the headquarters of his reluctant British allies—represented at that point in the war by a relatively small force—and personally pleaded with them to join him, reminding them, with uncharacteristic passion, that the survival of France was at stake. His eyes tearing, the usually-petulant British Field Marshall Sir John French, agreed. The British Expeditionary Force joined the counter-offensive.

The German high command was taken by surprise.

“It dawned on (them) at long last that the Allies had not been defeated, that they had not been routed, that they were not in disarray,” wrote Lyn MacDonald in her 1987 book on the first year of the war, 1914.

Instead, aided by reinforcements rushed to the front (although most of the ones that were engaged in the fighting came by train) Joffre and his British allies repulsed the German advance in what is now remembered as “The Miracle of the Marne.” Miraculous, perhaps, because the Allies themselves seemed surprised at their success against the German juggernaut.

“Victory, victory,” wrote one British officer. “When we were so far from expecting it!”

It came at the cost of 263,000 Allied casualties. It’s estimated that the German losses were similar.

The Taxis almost instantly became part of the Miracle—even if they didn’t contribute directly to it. “Unique in its scale and speed,” writes Arnaud Berthonnet, a historian at the Sorbonne University in Paris, “[the taxis episode] had a real effect upon the morale of the both the troops and the civilian population, as well as upon the German command. More marginal and psychological than operational and militaristic in importance, this `Taxis of the Marne’ epic came to symbolize French unity and solidarity.”

It didn’t even seem to matter that some of the cab drivers had complained about being pressed into service; or that when the cabs returned to Paris, their meters were read and the military was sent a bill. Somehow, the image of those stately Renaults rolling resolutely towards the fighting, playing their role in the defense of Paris and the survival of their republic, filled the French with pride.

While Paris was saved, the Battle of the Marne marked the beginning of the end of the War of Movement. By the end of 1914, both sides had dug in along a front that would eventually extend from the Swiss border to the North Sea. The nightmare of trench warfare commenced, and would continue for four more years. (It would end, in part, after what is often called the Second Battle of the Marne in 1918, fought in the same region, in which American Doughboys played an important role in a decisive counter-offensive that finally broke the back of the German armies).

The memory of the Marne and particularly its taxis, lived on. In 1957, a French writer named Jean Dutourd published a book called The Taxis of the Marne that became a best-seller in France, and was widely read in the Untied States as well. Dutourd’s book, however, was not really about the taxis, the battle or even World War I. It was, rather, a lament about French failings in the Second World War and a perceived loss of the spirit of solidarity that had seemed to bond civilians and soldiers in 1914. Dutourd—who, as a 20-year-old soldier, had been captured by the Nazis as they overran France in 1940—was aiming to provoke. He called the Taxis of the Marne “the greatest event of the 20th century...The infantry of Joffre, in the taxis of Gallieni arrived on the Marne...and they transformed it into a new Great Wall of China.”

Hardly, but historical accuracy wasn’t the point of this polemic. And some of the facts of the episode don’t seem to get in the way of the cabs’ enduring symbolic value.

So much so that school children still know about it. But at the Great War Museum, Stephane Jonard and his colleagues are quick to explain to them the truth of the Taxi’s role. “What’s important,” he says, “is that, at the moment we tell them about the real impact of the taxis, we also explain to them what a symbol is.”

And a century later, there are few symbols more enduring or important in France than the Taxis of the Marne.

For information on France’s World War I museum, in Meaux: http://www.museedelagrandeguerre.eu/en

For information on tourism to Seine et Marne and Meaux: http://www.tourism77.co.uk/