The day the great fire began on 2 September 1666, the diarist Samuel Pepys took to the safety of the south side of the river Thames and watched the flames gradually consume London’s medieval city. “It made me weep to see it … a horrid noise the flames made, and the cracking of houses at their ruin.”

Not everyone wept for what had been lost, however. Some saw an opportunity to transform London, to clear away the overcrowded warren of cobbled streets and narrow alleys that spread the fire and forge a greater, more elegant city from the ashes.

The great architect Sir Christopher Wren imagined a reconstructed capital full of wide boulevards and grand civic spaces, a city that would rival Paris for Baroque magnificence. Others dreamed of a rational, navigable city – London nailed down to a precise, uniform grid. And some conjured up a city of church bells, chiming in tower after tower, square after square.

This series of forgotten visions, masterplans for London produced in the aftermath of the great fire, form part of a new a new exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects: Creation from Catastrophe – How Architecture Rebuilds Communities. Although none of the designs came to pass in the last decades of the 17th century, the five original post-fire plans offer fascinating glimpses of what might have been if London had been set free of its medieval street pattern.

There was little doubt back then, in the immediate aftermath of the fire, that the city would look radically different when rebuilt. Five-sixths of the walled area of the city had been destroyed. One week after the final flames had gone out, Charles II issued a proclamation promising “a much more beautiful city than is at this time consumed”.

He also outlined his wish to impose “order and direction”, and promised main thoroughfares like Cheapside and Cornhill would be “of such breadth as may with God’s blessing prevent the mischief that one side may suffer if the other be on fire”.

Wren had already started work on his plan, one containing long boulevards connecting large plazas of the kind he saw on a visit to the French capital the previous year. He wanted to create a city of “pomp and regularity”.

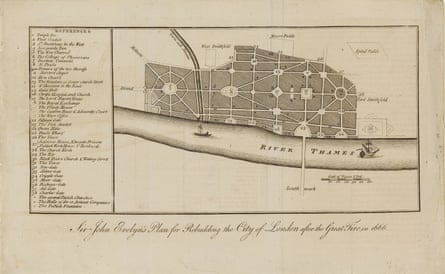

Writer John Evelyn’s design was very similar to Wren’s, if less detailed. Evelyn submitted his work for royal inspection two days after the great architect and followed large parts of Wren’s design. In both cases, a complete overhaul of the areas around Fleet Street and the Royal Exchange would have been required to accommodate huge, rond-point piazzas, and the area along the river Thames would have become one long, public quay.

Charles II admired Wren’s design, and made him one of six commissioners appointed to oversee rebuilding work. But unlike in Lisbon, where the Portuguese king ordered a completely new city after the earthquake of 1755, Charles would not get the chance to give Wren a blank canvas. Property owners soon asserted their rights and began building again on plots along the lines of the previous medieval street pattern.

There was no appetite (and because of war with the Dutch, no money) to get involved in legal battles with London’s wealthy merchants and aldermen. The king insisted only that the old roads be slightly widened and building standards improved. In February 1667, a Fire Court began sorting out remaining disputes, and the Rebuilding Act was passed to regulate the heights of new buildings (no more than four storeys) and the kinds of materials used (timber exteriors were banned, for obvious reasons).

“I think Wren’s is the most practical and interesting of all the plans,” says Charles Hind, Riba’s chief curator. “But personally I’m glad his scheme didn’t get built. I think it would have still been essentially un-English to masterplan on that scale. I rather like the higgledy-piggledy, piecemeal nature of London’s development over the centuries.”

According to the author John Schofield, a former archaeologist at the Museum of London, historians have exaggerated how much actually changed in the rebuilding of the capital after the great fire. Brick and stone did become more prevalent, and for a time the walled city would have been less dense and more middle-class. Aristocrats and the very wealthy had begun moving west to the new squares of Covent Garden and Bloomsbury, and many of the poorest tenants would have moved east to find cheap accommodation. Yet there was a remarkable degree of continuity: by the time all plots were filled again in 1676, Schofield thinks “the same people were moving back in”.

“It’s true that London has always been a mix of social classes,” Schofield says, “and it certainly stayed that way after the fire. But it’s possible that if Wren’s plan had happened, the classes would have been separated out. The main streets would have been transformed into something very grand and baroque, and that would have probably encouraged the crystallisation of the social classes into separate areas.”

Jes Fernie, curator of the Riba exhibition, agrees that if the Wren plan had come to pass, London might have become something akin to 19th-century Paris, when Georges-Eugene Haussmann’s vast redevelopment cleared the poor from the centre of the city.

“I imagine that if Wren’s plan had been approved, there would have been an element of social cleansing,” she says. “It could have resulted in a more coherent, less confusing city, but I suppose a lot of people would have struggled to afford to live in grand townhouses along the boulevards.”

Other intriguing masterplans came from draughtsman Richard Newcourt, scientist Robert Hooke, and Valentine Knight, an army officer who reputedly fought for the royalists in the English civil war. The king hadn’t actually asked for more ideas, but they submitted them anyway.

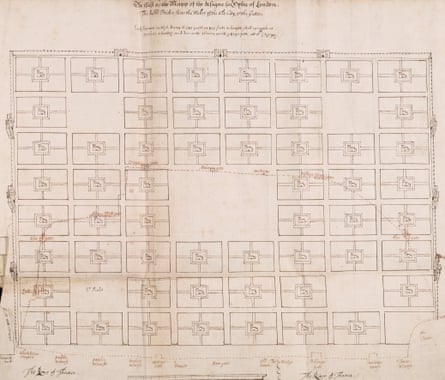

These designs were all variations on a grid system that later became prevalent in the development of cities in the United States. Newcourt’s eerily repetitive plan featured rigid rows of church squares within rectangular plots – a scheme that would influence the lay-out of Philadelphia in the 1680s.

“What’s so strange and lovely about that particular plan is that it’s so anti-capitalist, in a way,” says Fernie. “All of the others recognise London as a trading entity, based around trading centres. But this plan only outlines for churches, as if to say, ‘all we need is God’.”

Hooke was a polymath and well-respected figure in royal circles, and although his plan was put to one side, he was given a role surveying London’s streets as they were widened. He later worked with Wren designing the Monument to the Great Fire of London (finished in 1677), which stands near London Bridge.

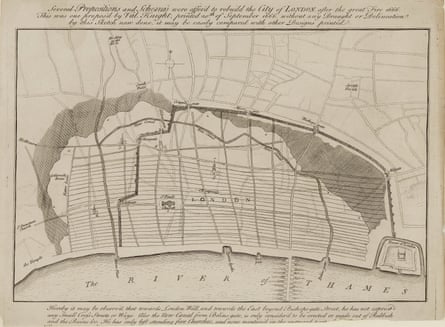

Knight’s plan for London enjoyed the least favourable response. He proposed two main thoroughfares and long rows of tenements in between. Knight was also bold enough to suggest the king could raise large sums from rents and fees charged for using the canal. Charles II was greatly offended by the suggestion that he would want to “draw a benefit to himself from so public a calamity of his people” – so he had Knight thrown in jail.

Hind does not like to imagine modern London had Knight’s – or any of the grid plans – found favour. “It would have been dull,” he says. “I’ve always thought the grid, when you’re thinking about beautiful urban planning, is a dead duck. With the majority of American cities, when you’re looking down these long, endless canyons, there isn’t the same regard to the picturesque – you don’t have major buildings to organise your view.”

Urban designer Adrian Jones, author of Towns in Britain, disagrees. “I think grid systems can become exciting when they cease to become entirely predictable and regular,” he says. “San Francisco is the best example of a hilly topography that makes the grid system very dramatic. You get that in Glasgow too, which has an American-style grid but it’s not dull or monolithic.

“It might be difficult to envisage the City of London based on a grid, but I don’t think it’s a frightening idea,” Jones adds. “I think almost inevitably it would have become more interesting over time when things came along to mess it up and make it less rigid.”

An intriguing question about the post-fire plans for London is whether one tabula rasa redevelopment would have invited fresh forms of top-down planning over the centuries. If you’ve cleared the past away once, it becomes easier to do it again and again.

London continues to evolve, but the city has resisted wholescale change. Today’s chaotic megacity manages to incorporate ancient street and road patterns, village structures and architecture from almost every era. So many layers of history have survived to form its current fabric. Perhaps the failed plans of the 1660s show the folly of attempting to compose one kind of London for the ages.

Christopher Wren, of course, would get his defining masterpiece: St Paul’s Cathedral, declared complete in 1711. Yet shaping the very nature of the city would elude him, as it did everyone else.

Creation from Catastrophe is on at the Riba Architecture Gallery, London W1, from 27 January–24 April – entrance free.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion