The 95,000 Chinese farm labourers who, almost a century ago, volunteered to leave their remote villages and work for Britain in the first world war, have been called "the forgotten of the forgotten".

The contribution made by the Chinese Labour Corps was barely recognised at the end of the war, and has almost been obliterated since. There is no tribute to them among Britain's 40,000 war memorials, there are no descendants in Britain because they were refused any right to settle after the war, they were literally painted out of a canvas recording all the nations who joined the war effort, and many of the records of their service were destroyed in the blitz of the second world war.

However, a campaign has now been launched by the Chinese community in Britain to create a permanent memorial in London to the Chinese Labour Corps and the dirty, dangerous, vital work they did behind the lines on the western front.

Steve Lau, chair of the Ensuring We Remember campaign, was invited to the service of commemoration at Glasgow Cathedral 10 days ago. "My invitation was probably the first time the British government properly recognised the Chinese Labour Corps since the end of the war," he reflected.

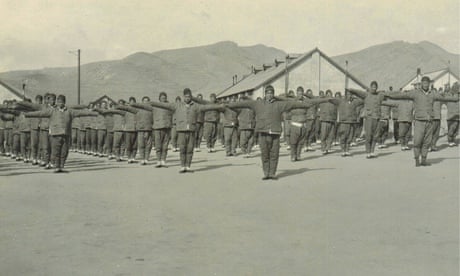

Recruitment of the Chinese began in 1916 as ever escalating casualties meant labourers became disastrously scarce. Many came from such remote farms that when they reached the tall buildings and busy waterfront of Shanghai, they thought they had arrived in Europe. In fact it was only the start of an appalling journey on which many died – by ship across the Pacific, six days crossing Canada in sealed trains to avoid paying landing taxes, on by ship to Liverpool, by train again to Folkestone, and on to France and Belgium, where they lived in labour camps and worked digging trenches, unloading ships and trains, laying tracks and building roads, and repairing tanks.

Some who died on the voyage are buried in Liverpool, and 2,000 more lie in Commonwealth war graves, but some sources believe 20,000 died. They worked 10-hour days, seven days a week, and had three holidays including Chinese New Year. When the war ended and other men went home, they worked on until 1920, clearing live ordnance and exhuming bodies from battlefield burials and moving them to the new war cemeteries.

China declared war on Germany in August 1917, when a German torpedo sank the French ship Athos, with the loss of 543 Chinese lives. In 1919 China refused to sign the treaty of Versailles, in bitter disappointment over the breaking of a promise that in return for their support for the allies, the Shandong peninsula would be returned from Japanese control.

Lau said that when Britain distributed 6m commemorative medals to all who took part in the war, those received by the Chinese bore only their numbers, not their names, and were bronze, not silver. Painfully symbolically, the Chinese were also painted out of a giant canvas exhibited in Paris at the end of the war. It was believed to be the largest painting in the world, and showed a victorious France surrounded by her allies. It was begun in 1914, but had to be changed in 1917 to include the arrival of the United States – the space was found by painting over the Chinese workers.

When the Imperial War Museum reopened last month after a £40m rebuild, the campaigners were saddened but not surprised that there was no mention of the Chinese labourers' contribution in the new first world war gallery.

The broken promise at Versailles led in part to Lau's own birth in Birmingham, son of a Chinese chef. His father left as a boy when, as predicted, war broke out again with Japan over Shandong, making his way first to Hong Kong and then England.

The campaign to create a permanent memorial in central London, to be unveiled in 2017 sited either in Southwark or Westminster, is backed by the Chinese embassy and the Chinese in Britain Forum.

Lord Wallace of Saltaire, who attended the launch representing the Foreign Office and is a member of the official advisory group on the first world war commemorations, said the campaign was a useful corrective to what he called "the Daily Mail approach" to the war, portraying plucky little England standing alone against the enemy. "It was never a purely English effort: it required the effort of a great many people from a great many countries, willingly or unwillingly."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion